And intriguing excerpt from Richard A. Serrano's, Last of the Blue and Gray (Smithsonian Books) can be read here.The last veteran who said he fought for the Union was Albert Woolson; Walter Williams said he was the last Confederate. One of them indeed was a soldier, but one, according to the best evidence, was a fake. One of them had been living a great big lie.

Reflections, observations, random thoughts and bon mots, relating to the literary and geographic landscapes of American history. And book reviews too.

Friday, December 13, 2013

Excerpt from Smithsonian's, "Last of the Blue and Gray"

Saturday, December 07, 2013

Travelogue: Battle of Apache Pass

In September I attended the 34th Annual Order of the Indian Wars Assembly in Tucson—“On the Trail of Geronimo"—for a few days of talks and tours. Some of this country's top authorities on the Apache were in attendance, including Ed Sweeney, who has authored biographies of both Cochise and Mangas Coloradas. In four days we covered a lot of ground with stops at Mission San Xavier del Bac, San Jose de Tumacacori Mission Church, The Horse Soldier Museum, Fort Huachuca, Tombstone, the Arizona Historical Society Museum (with a special display on Geronimo), Fort Lowell, Dragoon Springs, the American Indian Museum (Amerind). Along the way we drove past Cochise’s stronghold.

For me, the highlight of the weekend was our Sunday hike through the heart of Apache Pass. Our trail took us across a clearly discernible stretch of the Butterfield Overland Mail Route, near the site of the Apache Pass station. Apache Pass station also marks the scene of the infamous Bascom Affair—known to the Apache as “Cut the Tent—the betrayal of Cochise that, along with the execution of some of his family members, led to eleven years of unremitting warfare between the U.S. and the Chiricahua Apaches.

|

| Butterfield Overland Trail near Apache Station |

Continuing beyond this point, we passed Apache Spring, the water source so critical to travelers in the area, and a favorite spot for the Apaches to ambush passers-by. Here, too, is the ground over which the Battle of Apache Pass was fought on July 15-16, 1862, when a detachment of Colonel James H. Carleton’s California Column under Captain Thomas L. Roberts twice drove Apaches under Cochise and Mangas Coloradas from defensive positions on the high ground above the spring.

To secure this important mountain pass once and for all, Carleton established Fort Bowie, and our hike continued past the ruins of the original fort, as well as the grounds of the relocated fort. Today, there is a NPS installation there, with a small museum and bookstore.

The Battle of Apache Pass sesquicentennial fell squarely between the sesquicentennials of the Seven Days Battles, and Second Bull Run, so you're forgiven if you forgot to commemorate it.

|

| A mountain howitzer similar to the two used by Roberts to dislodge the Apaches. |

|

| Historian Neil Mangum on the Battle of Apache Pass |

|

Site of the Bascom Affair |

Friday, November 29, 2013

Grant, Sherman, and Sheridan slept here. Joe Hooker and Kit Carson too. . . my kids are unimpressed

The operative phrase is, "according to local tradition."

But it could have happened. |

| Blue Wing Inn, across the street from the Sonoma Mission |

We have three sons spread out over a number of years, and it dawned on me that in the lifetime of our three boys, when visiting my brother we have routinely skirted Sonoma proper in favor of more direct and less congested routes. Even the 19- and 15-year-old would have been too young to remember those occasions when we used to walk around the town square. What a grand opportunity to expose the young'uns to some essential Golden State historic sites. All of our kids, when they passed through 4th grade, participated in the requisite study of the California missions (reportedly, and I believe it, there is an underground market for foam-core models of Spanish missions well supported by 4th grade parents), and here in Sonoma, on the plaza, is the northern-most of all the Californian missions. Not only that, but other historic structures abound, like the barracks, and look over there—a monument commemorating the Bear Flag Revolt which happened right on this spot!

First rule, and I should have known better, don't go down to the town square in Sonoma (or any place in the Wine Country, or any other popular destination in California) on a day when nearly everyone is off work, like weekends or holidays. It's crowded, and the road infrastructure doesn't support the volume. Second rule, don't ever think that your kids will even remotely share your interests in history. Don't think they will shiver in awe at the significance of some patch of grass or pasture, or look in wonder on what today, you have to admit, is just a ratty old shed that preservationists—through herculean efforts and much expense—managed to keep from falling down. When we got to the plaza, the two younger boys insisted on "waiting in the car" while we older trio took a stroll. Third rule, don't even try to force them to come with you, because their clinical lethargy, their superhuman disinterest, and their involuntary robo-chants of "can we go now" will detract from your own very real pleasure. No, just crack the windows and say "see you in a bit."

Oh how I enjoyed revisiting California's largest plaza.

|

Blue Wing Inn |

|

| Mission San Francisco Solano (Sonoma Mission) Founded July 4, 1823 |

|

| Operation Steal California from Mexico, Phase One |

Wednesday, November 20, 2013

Review: Voices of the American West

Voices of the American West, Volume 1: The Indian Interviews of Eli S. Ricker, 1903-1919, by Eli Ricker, edited by Richard E. Jenson, University of Nebraska Press, 2012. 495 pages.

Voices of the American

West, Volume 2: The Settler and Soldier Interviews of Eli S. Ricker, 1903-1919,

by Eli Ricker, edited by Richard E. Jenson, University of Nebraska Press, 2012.

470 pages.

Eli Ricker, a Civil War veteran who marched with Sherman,

tried his hand at a number of occupations after the war, including lawyer,

judge, and newspaperman. He came to live in Chadron, Nebraska, in 1885, not far

from Fort Robinson, where Crazy Horse had been killed just eight years earlier.

Chadron was also in close proximity to the battlefields and reservations of

western South Dakota, and it was at Chadron around the turn of the century that

Ricker began conducting interviews, compiling notes, and doing research on the

rapidly changing “Old West.” His intention was to write a book he called, “The

Final Conflict Between the Red Men and the Palefaces,” but a quarter century

later he was still gathering material.

As early as 1903, Ricker, who spent two full winters on the

Pine Ridge Reservation -- began writing down eyewitness accounts about what

transpired at Wounded Knee both from the 7th Cavalry perspective as

well as from survivors of Big Foot’s Lakota Band. Ricker was sympathetic to the

plight of Indians at a time when white Americans nearly universally regarded

them as savages. Indeed, he advanced the radical proposition that Indian historical

testimony was as valuable and legitimate as that of the white man. One of Ricker’s notes, quoted in the

Introduction, gives a sense of his enlightened sensibilities: “The Indians

sneer at the whiteman’s conventional reference to the Custer massacre and the

Battle of Wounded Knee. They ridicule the lack of impartiality of the whites in

speaking of the two events – when the whites got the worst of it it was a

massacre; when the Indians got the worst of it it was a battle.”

Alas, Ricker’s long-researched book never materialized. A

stint at the U.S. Office of Indian Affairs in Washington, D.C. allowed him to

fortify his research, but also served to overwhelm him with the amount of Indian

resources demanding his attention. Already past the age of 60 when he began the

project, Ricker died before he could complete more than some sections of a

rough draft.

Ricker left behind stacks of tablets containing

transcriptions of his interviews -- a treasure trove of unique and invaluable

oral histories. Happily, after selling much of his collection, including his

library, Ricker’s family donated the precious tablets to the Nebraska State

Historical Society, where they were received on November 2, 1926. The

collection remained relatively obscure for decades, though some Western

historians like Robert Utley have accessed it in support of their own studies

(Nebraskan Mari Sandoz cataloged and collated the interviews, and

incorporated some of the material in her writings as well).

Finally, the 2005 publication in two volumes of Voices of the American West has made

Ricker’s painstaking work readily available to scholars and history buffs alike

(being reviewed here are the 2012 paperback releases of both volumes). Editor

Richard Jensen has done an expert job organizing the Ricker material, intuitively

devoting one volume to Indian interviews, and the other to Settlers and

Soldiers. Within each volume, interviews are grouped together into major

subject areas. Volume one includes chapters on The Garnett and Wells

Interviews, The Ghost Dance and Wounded Knee, and The Old West – Indians and

Indian Fights. Volume two chapters include: Wounded Knee, Little Bighorn,

Beecher Island, Lightning Creek Incident, Biographical Sketches, and The Old

West.

Though there is a heavy emphasis on military affairs in the interviews, they also present perspectives on a broad range of other aspects of the Old West, from life on the reservations to the fur trade. Fully 200 pages of volume one are devoted to interviews with William Garnett and Philip F. Wells, mixed-blood men who spent decades as Lakota interpreters. Garnett and Wells, in addition to discussing warfare, offer insights on treaties, Sun Dances, Sioux customs, religion, and languages. Garnett, sometimes called Billy Hunter, is reported to be the son of Confederate General Richard B. Garnett, who died in Longstreet’s assault at Gettysburg. While stationed at Fort Laramie before the war, Garnett took an Oglala woman, named Looks at Him, as his common-law wife, resulting in the birth of William.

Though there is a heavy emphasis on military affairs in the interviews, they also present perspectives on a broad range of other aspects of the Old West, from life on the reservations to the fur trade. Fully 200 pages of volume one are devoted to interviews with William Garnett and Philip F. Wells, mixed-blood men who spent decades as Lakota interpreters. Garnett and Wells, in addition to discussing warfare, offer insights on treaties, Sun Dances, Sioux customs, religion, and languages. Garnett, sometimes called Billy Hunter, is reported to be the son of Confederate General Richard B. Garnett, who died in Longstreet’s assault at Gettysburg. While stationed at Fort Laramie before the war, Garnett took an Oglala woman, named Looks at Him, as his common-law wife, resulting in the birth of William.

Maps, illustrations, useful appendixes and an exceedingly

generous index enhance the text, and Jensen’s voluminous endnotes not only

demonstrate his utter mastery of the subject matter (Jensen was a senior

research anthropologist at the Nebraska State Historical Society), but render

the oral histories exponentially more useful and interesting.

Bison Books, the trade paperback line of the University of Nebraska Press, has consistently released some of the most fascinating and

valuable works of American history. Voices of the American West is another

brilliant offering in a catalog of over 900 in-print titles spanning more than

50 years.

Tuesday, November 19, 2013

150 years ago -- the Gettysburg Address

One of only five known copies of the Gettysburg Address written in Lincoln's hand, this one resides at the Cornell University Library. Lincoln sent it to historian George Bancroft for inclusion in a special publication intended to provide assistance to soldiers.

Friday, November 15, 2013

We pass over the silly remarks of the president

Timely retraction. . .

In the editorial about President Abraham Lincoln’s speech delivered Nov. 19, 1863, in Gettysburg, the Patriot & Union failed to recognize its momentous importance, timeless eloquence, and lasting significance. The Patriot-News regrets the error.

In the editorial about President Abraham Lincoln’s speech delivered Nov. 19, 1863, in Gettysburg, the Patriot & Union failed to recognize its momentous importance, timeless eloquence, and lasting significance. The Patriot-News regrets the error.

Hat tip to Mother Jones.

Monday, October 28, 2013

Strolling down memory lane: South Bay Civil War Roundtable

|

| DW, left, and TPS, August 24, 2013 |

Way

back in 1988, my wife and I flew from San Francisco to San Diego where I was

excited to attend the Annual West Coast Civil War Conference, then organized by

Jerry Russell of Civil War Round Table Associates. I had just finished reading

McPherson’s, Battle Cry of Freedom, and relished the prospects of listening to

some authors hold forth on a variety of subjects. The featured historian was

William C. “Jack” Davis, a tremendously knowledgeable and entertaining speaker.

He told a story that had the audience laughing so hard, I remember it to this

day (maybe some of you have heard it at other events – it involved him

traipsing around his house with a Civil War saber, looking for a possible

intruder). Bob Younger of Morningside Books was also there, and so I dropped a

lot of cash on new reading material.

That

conference was also where I met Ted Savas, who was then living in San Jose. He

and his wife Carol, and Anne and I, gravitated together -- some of the only

people in attendance who were still in their 20’s -- and the only four who had

come down from Northern California (or so it seems to me now). We soon learned

we had other things in common, such as Ted and I both hailing from Iowa (my

mother grew up in his home town, and my father grew up nearby).

Not

long after returning to the Bay Area, we got together at the Winchester Brewpub

– just down the street from the legendary Winchester Mystery House – and started

planning the creation of the South Bay Civil War Roundtable (at that time,

there were roundtables in San Francisco, and on the Peninsula, one in the East

Bay, but nothing in the area of San Jose, the most populous city in the area).

Our

first meeting was held at Ted’s house with about 14 people in attendance. Ted

became the first president, and I took up duties as the newsletter editor (and

eventually became the 2nd president). At the first meeting, Zoyd

Luce spoke on Benjamin “The Beast” Butler. Ted spoke the following month on

Longstreet’s Suffolk Campaign, and I spoke at the third meeting on John Hunt

Morgan’s Indiana/Ohio Raid. And just like that, we were off to the races,

eventually finding a regular meeting place and steadily increasing the

membership.

Within

the next couple years, our group hosted the West Coast Conference after it had

devolved into a moribund affair, and Jerry Russell was imploring the round

tables themselves to take turns organizing it. The year after San Diego it was

held in a dingy motel in Burbank, with very low attendance. It was in its death

throes, and Russell was ready to give up. The following year we hosted the

event near Fisherman’s Wharf in San Francisco, got the word out far and wide,

and saw a great crowd turn out to hear a roster of speakers topped by Robert K.

Krick, whose compensation included two tickets to the next 49ers game. That San

Francisco conference was also where Ted and I debuted volume 1, number 1 of

Civil War Regiments journal, which, along with a number of stand-alone campaign studies, would consume so much of our lives for years

to come. After San Francisco, the Long Beach CWRT held a large, well-attended conference with James McPherson, and the meeting has been a

rollicking success ever since.

It’s

no exaggeration to say that the South Bay CWRT revived and re-energized the West

Coast Conference, which today routinely sees 100+ in attendance, in nice

venues, and with top-flight historians and authors (Richard Hatcher and Craig

Symonds will be on hand next month).

At

some point, I don’t remember when exactly, I stopped attending meetings of the

South Bay CWRT in favor of the CompuServe forum I have administered for nearly

20 years, effectively an online CWRT whose members discuss the Civil War era

all year long, and meet in person every spring to tour a battlefield. I

eventually moved on to work at Stanford University Press, and Savas Woodbury Publishers became Savas Publishing, then Savas Beatie, and anyone

who loves books on the Civil War knows what a strong presence Savas has been in that

arena all these years later.

At

some point, I don’t remember when exactly, I stopped attending meetings of the

South Bay CWRT in favor of the CompuServe forum I have administered for nearly

20 years, effectively an online CWRT whose members discuss the Civil War era

all year long, and meet in person every spring to tour a battlefield. I

eventually moved on to work at Stanford University Press, and Savas Woodbury Publishers became Savas Publishing, then Savas Beatie, and anyone

who loves books on the Civil War knows what a strong presence Savas has been in that

arena all these years later.

I’m

pleased to say the South Bay CWRT is still going strong as well, compiling over the years a long record of generous donations to Civil War preservation organizations. When I saw

that they were celebrating their 25th anniversary (which I calculate

to be March of 2014), and that Ted was the guest speaker at the annual summer

picnic, I decided to surprise him. We had not seen each other in over 10

years. I wish I could describe the look on his face when he glanced my way for the

first time after arriving.

It was a lot of fun, and many memories were refreshed. Ted gave a

masterful, no-notes talk on “The Battle of Payne’s Farm, November 27, 1863:

Command & Competency During the Mine Run Campaign.” That, in itself, caused

many more memories to surface, as I was with Ted at Payne’s Farm when he first

began researching that fight, and when, using metal detectors, he established

an artillery position by finding canister balls in the woods right where he surmised they would be found. He found the remnants of canister. My metal detector was so poor it

literally could not detect a quarter sitting on the surface. I know because I tried.

It was a lot of fun, and many memories were refreshed. Ted gave a

masterful, no-notes talk on “The Battle of Payne’s Farm, November 27, 1863:

Command & Competency During the Mine Run Campaign.” That, in itself, caused

many more memories to surface, as I was with Ted at Payne’s Farm when he first

began researching that fight, and when, using metal detectors, he established

an artillery position by finding canister balls in the woods right where he surmised they would be found. He found the remnants of canister. My metal detector was so poor it

literally could not detect a quarter sitting on the surface. I know because I tried. Tuesday, October 15, 2013

Indians and Braves, but no 7th Cavalry

from the Times-Georgian. . .

. . . the Heard County High School football team is hoping to rebound from a frustrating opener this week when it travels to Chattanooga for a powwow with the Indians at 7:30 on Friday night at Little Big Horn Stadium in Summerville.

Sunday, October 13, 2013

Review: Smithsonian Civil War

Smithsonian Civil War, Inside the National Collection, edited by Neil Kagan and Stephen G. Hyslop (Smithsonian Books, 2013).

Establishment of the Smithsonian predates the Civil War by 15 years. The iconic "Castle" on Washington's National Mall was completed in 1855, and became home to the institution's first secretary, Joseph Henry, and his family, who witnessed some of the opening scenes of the war. Young Mary Henry, Joseph's daughter, recorded in her diary on July 16, 1861, "We went up into the high tower to see the troops pass over into Virginia." Today, the Smithsonian has grown to nineteen museums and nine research facilities, which together preserve tens of thousands of objects related to the American Civil War, including Mary Henry's diary.

Smithsonian Civil War is the only book of its kind, that I know of, to present together in a single volume some of the most important and representative Civil War artifacts from 13 separate Smithsonian entities (the press release mentions 12 museums and research centers). According to the introduction, curators, archivists, historians, interns, and volunteers (more than 100 staff members) "spent hours in locked vaults, storage rooms, and cabinets, researching and evaluating items" for inclusion, after which the Civil War 150 Editorial Committee debated which items held the "greatest historical value or the most compelling stories attached to them." The results of that exhaustive selection process are positively spectacular.

This lavishly illustrated, brilliantly assembled coffee table book couldn’t have come at a better time, presenting an "exhibit between hard covers" at a time when the dysfunctional government of the United States has shuttered its doors.

Commemorating the Civil War Sesquicentennial, Smithsonian Civil War offers 150 thematic essays written by a large number of Smithsonian contributors. Though organized chronologically, the entries amount to stand-alone articles covering a broad spectrum of topics—pre-war through Reconstruction.

The 550 full-color photographs constitute the volume's real strength—highlighting, with high production values, some of the most rare and fascinating objects in the Smithsonian holdings. A number of items will be familiar, such as Lincoln's top hat or the bullet-riddled tree stump from Spotsylvania, but many other objects pictured here have never been on public exhibit.

Of particular interest are the instances where related objects from different repositories are brought together for the first time. For instance, a portrait of J.E.B. Stuart from the National Portrait Gallery, sits opposite an image of a pistol from the National Museum of American History, a present to Stuart from Major Heros von Borke. Likewise, from the same museums, a portrait of John Brown is featured together with images of weapons Brown and his followers carried in Kansas, and Virginia, including one of the hundreds of pikes Brown stockpiled at Harpers Ferry.

The collections at the NPG and NMAH are most represented, but this eclectic assemblage also features contributions from the Air and Space Museum (Civil War-era aircraft designs), the Postal Museum (printing plate for Confederate stamps), the Museum of Natural History (ornithological specimens), the Museum of African American History and Culture (slave tags), and others.

As impressive as this work is, some of the narrative will raise eyebrows among critical readers. A few examples: the entry on Harriet Beecher Stowe perpetuates the legend that when Lincoln met Stowe, "he reportedly said to her, 'So you're the little woman who wrote the book [Uncle Tom's Cabin] that started this great war!'" While the author did at least use the qualifier "reportedly," it's surprising to see the anecdote given passing credence in a Smithsonian publication. The story is entirely apocryphal, a product of Stowe family lore, and did not appear in print until 34 years after the fact by a Stowe biographer.

In the essay, "Sherman Moves South," we read that after capturing Atlanta, "Sherman ordered Atlanta evacuated and then burned everything he considered of military significance. Nearly one-third of the city went up in flames. Enraged, Hood wrote that his actions surpassed 'in studied and ingenious cruelty, all acts ever before brought to my attention in the dark history of war.'" Students of the Atlanta Campaign, however, will note that the correspondence in question dates to September 7, about the order to evacuate civilians. The burning of Atlanta did not occur until mid-November, when Sherman left on his March to the Sea.

More surprising, perhaps, is the entry entitled, "Searching for Shoes at Gettysburg," which begins with, "A search for shoes has often been cited as the spark that ignited a blistering three-day battle in the bucolic fields around Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, on July 1, 1863." General A.P. Hill is pictured in the article, across from a full-page photo of brogans, with the caption explaining that Hill unwittingly launched the battle by "sending in Henry Heth's division to 'get those shoes. . .'" This essay goes so far as to quote Heth's 1877 letter to the Southern Historical Society, in which he fleshes out the shoe story. Heth's after-action report, written two months after the battle, makes one mention of shoes (among other supplies he was seeking), but the consensus among historians is that the shoe story was concocted by Heth to excuse the fact that he brought on a general engagement despite explicit orders not to do so. I'm fairly certain that the National Park Service considers the shoe story as officially debunked.

These examples are not terribly significant flaws since, as mentioned, the great power of this work are the photographs, and the 150 articles are generally succinct and spot-on, chock-full of useful information on a rich constellation of subjects. The barcode lists this book at $40, but I see it can be purchased in any number of places online for around $24 -- a good price for such a pretty book.

Wednesday, October 09, 2013

Gettysburg Magazine acquired by University of Nebraska Press

The University of Nebraska Press will take over publication of Gettysburg Magazine in 2014. They're looking for a new editor.

Saturday, October 05, 2013

Review: Decided on the Battlefield, Grant, Sherman, Lincoln and the Election of 1864

Decided on the

Battlefield: Grant, Sherman, Lincoln and the Election of 1864, by David

Alan Johnson (Prometheus Books, 2012).

Judged solely by its cover, this Prometheus release promised

to be an interesting and insightful examination of the critical 1864

presidential election – how it came to unfold the way it did, and the possible

ramifications to the nation had Abraham Lincoln lost his bid for re-election.

Unfortunately, there is very little new introduced that could not have been gleaned

from a general history of the war, and the author’s almost complete reliance on

secondary sources (Bruce Catton is cited 43 times, Carl Sandburg 21, and so

on), makes for a shallow treatment of a deep subject. Both the seasoned student

and the well-read buff are likely to be dissatisfied with what, in the end,

amounts to a simple affirmation of what many have long understood to be a Civil

War truism—that the ascendancy of Grant and Sherman, and their

slow-but-steady battlefield successes, particularly the capture of Atlanta in

the run-up to the election—assured the reelection of Lincoln, and ended any

hope of an independent Confederacy.

Decided on the

Battlefield is not without merit. It is an easy read with a serviceable

account of military events. Informed as it is by the popular histories of

Catton, Shelby Foote, Doris Kearns Goodwin, et. al., the story is held together

by an efficient, quick-moving narrative adorned with some of the literature’s

most familiar anecdotes. Most interesting, to me, was the author’s discussion

of the main party’s respective national conventions, and for those topics—at

least—official proceedings were liberally consulted.

Whatever the book’s shortcomings in the main text, it goes completely

off the rails in the Epilogue. To ram home his point about the over-arching

importance of Lincoln’s victory, the author devotes 18 pages to a bizarre and thoroughly

pointless reverie about how things would have been different had Lincoln gone

down to defeat. He doesn’t merely speculate about the Balkanization of North

America, but paints an elaborate alternate history up through the Cold War and

into the 1980s, even imagining, by name, the presidents of five separate

American countries (the U.S., the C.S.A., Texas, Utah, and California, the last

governed by President Ronald Reagan). In this fantasy, the C.S.A. (eventually

the Confederate Commonwealth after annexing Cuba) did not send troops overseas

in WWI, but since Tennessee seceded from the C.S.A. and rejoined the U.S. in

1866, U.S. troops in the First World War do include men from the Volunteer

State. Thus, we’re told, Lincoln’s election loss in 1864 would have had no

bearing on Tennessean Alvin York winning the Medal of Honor for actions in the

Argonne Forest. I’m pretty sure the author didn’t get that last part from Bruce

Catton.

Thursday, September 19, 2013

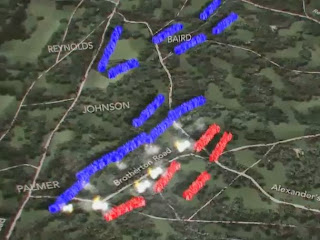

150 Years Ago: Chickamauga

150 years ago today:

The Battle of Chickamauga. Click on the photo below to visit Chickamauga resources at The Civil War Trust, including an outstanding animated map. One veteran of that battle, James A. Garfield -- Chief-of-Staff to Union commander William Starke Rosecrans, went on to become the 20th president of the United States.

132 years ago today:

President Garfield died, 80 days after having been shot twice in the old Baltimore and Potomac railroad terminal (southwest corner of present day Sixth Street and Constitution Avenue, Washington, D.C.). He was two months shy of his 50th birthday.

The Battle of Chickamauga. Click on the photo below to visit Chickamauga resources at The Civil War Trust, including an outstanding animated map. One veteran of that battle, James A. Garfield -- Chief-of-Staff to Union commander William Starke Rosecrans, went on to become the 20th president of the United States.

132 years ago today:

President Garfield died, 80 days after having been shot twice in the old Baltimore and Potomac railroad terminal (southwest corner of present day Sixth Street and Constitution Avenue, Washington, D.C.). He was two months shy of his 50th birthday.

|

| Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper, July 11, 1881 |

Friday, September 13, 2013

Smithsonian article on George Henry Thomas

|

| (Rudy Ayordoa / David Perry Collection) |

Catching Up With "Old Slow Trot"

by Ernest B. Furgurson

Stubborn and deliberate, General George Henry Thomas was one of the Union's most brilliant strategists. So why was he cheated by history?

Read the full article here:

Monday, September 02, 2013

Lee was a traitor, Thomas a man of honor -- thoughts from an unreconstructed Yankee

“I think that Robert E. Lee, as a traitor and betrayer of his solemn oath before God and the Constitution, was a much greater terrorist than Osama Bin Ladin… after all, Lee killed many more Americans than Bin Ladin, and almost destroyed the United States. What do you think?”

So wrote Lt. Col. Robert Bateman in an August 14, 2013 Esquire essay entitled, The Meaning of Oaths and a Forgotten Man. You can read the full essay here.

Monday, August 19, 2013

"Articulating the unspeakable: Art-making during wartime"

|

| This undated handout image provided by the Smithsonian American Art Museum shows Frederic Edwin Church's 1861 oil on paper "Our Banner in the Sky."

(Credit: AP/Smithsonian American Art Museum)

|

Sunday, August 18, 2013

Meanwhile, some good reading from Smithsonian.com

|

| Sneden Collection, Virginia Historical Society |

The map, which shows in rich detail not only the engagement, but the layout of Civil War-era Washington, is part of one of the more remarkable compilations of Civil War maps and artwork in existence: the Sneden Collection at the Virginia Historical Society. “It’s an incredible body of visual information about the Civil War,” says the Society’s head of program development, Andrew Talkov. The collection includes his wartime diary, and the so-called “Sneden Scrapbook,” a loosely organized compendium of maps and drawings that he compiled after the war, documenting not only his own experience, but other battles as well. Often known as “Jubal’s Raid” because it bore the stamp of one of Robert E. Lee’s boldest and ablest generals, the attack on Washington was part of an effort to relieve pressure on Lee’s army in Petersburg, Virginia.

==========

Read the full article here.

And if you have a few more minutes, check out this slide show on Gettysburg Artifacts from the Smithsonian Collection.

|

| U.S. Army Canteen (Armed Forces History, NAMH) |

Back from the Mountain Top

|

| View of the Rocky Mountains from atop Crested Butte Mountain, Gunnison County, Colorodo. |

Speaking of cave features, on our way through Colorado Springs we stopped to tour Cave of the Winds, a place I had once visited as a 17-year-old. This time I was interested to learn that inside, near the original entrance, are three stone memorials to Abraham Lincoln, Ulysses S. Grant, and Robert E. Lee. Reportedly, 19th century visitors were asked to stack a stone on the memorial of the man they admired most, and Grant's pile grew the largest. At some point Lee's stone pile collapsed, and has resisted efforts to restore it. Make of that what you will. And there you have a Civil War connection under the very earth and rocks of a Colorado mountain.

|

| Cave of the Winds stone memorials, left to right: Lincoln, Grant, Lee. |

Wednesday, July 03, 2013

Jimmy Carter -- first president from the Deep South since the Civil War

Back in April I spent a day at the Andersonville prison site, near Americus, Georgia, as reported in this blog post. The next morning, a Sunday, my wife Anne and I had to drive the nearly three hours back to the Atlanta airport to return to the Left Coast. More or less at the last minute, we decided to make a short detour from Americus over to nearby Plains, to see the Jimmy Carter National Historic Site. The two or three hours we spent looking around Plains turned out to be one of the highlights of the weekend.

I have always liked Jimmy Carter. He may have been an ineffective president in many ways—and he faced some pretty complicated issues—but I have considered him to be the most genuinely principled man to hold that office in my lifetime. I don't want to start a debate here about the Shah, Nicaragua, the hostage crisis, thermostats, or the Panama Canal, but anyone who looks at Carter's life to-date must come away with the impression of a good and decent man. The work he's done post-presidency, through the Carter Center, through Habitat for Humanity, has transformed untold lives here, and abroad.

Plains, Georgia is quaint, and the National Historic Site is scattered in and around the town. There's the train depot, which was campaign headquarters in 1976. There's Billy's gas station. Outside of town is the boyhood farm, where you can peer into young Jimmy's bedroom. The old high school is the Visitor Center. A film is shown in the classic auditorium, where Jimmy and future wife Rosalynn were called to daily assemblies (assemblies including prayer in those days). The hallways and classrooms of the high school are devoted to exhibits of the Carters' lives, from childhood, to the White House, and beyond.

In the bookstore, I picked up a copy of An Hour Before Daylight, Memories of a Rural Boyhood, and I started reading it on the plane ride home. I wasn't expecting to find it so engaging, but over the next week or so I couldn't wait to crack it open in every leisure moment. It was a fascinating account of life on a big farm in Depression-era Georgia, with candid discussions about race relations in a Deep South community only six decades removed from the Civil War (by the time Jimmy was born). One of Carter's great-grandfathers served with the Sumter Flying Artillery, Plains being in Sumter County.

The early lives of our presidents have always fascinated me, and Carter's story is uniquely, quintessentially American. I was so moved by the book, and a life well lived, that when I finished reading I penned a letter to the former president. It's the very first time I've written to an erstwhile Leader of the Free World, and I naturally had no expectation that he would ever read it. I complimented him on his book, and the important work he's done.

One thing in particular I was curious about was whether people growing up in Plains, and Americus, in the 20's and 30's—particularly school children—ever heard about the notorious Civil War prison down the road at Andersonville (MacKinlay Kantor's Pulitzer Prize-winning novel, Andersonville, was not published till 1955). Was it spoken of in polite company? Was there a local version of events to account for it? I mailed my letter to Jimmy Carter on May 14.

Astonishingly, on July 2 I received a letter back, the original of mine in the margin of which Mr. Carter scribbled a note. I got my answer and I'm satisfied with it.

I have always liked Jimmy Carter. He may have been an ineffective president in many ways—and he faced some pretty complicated issues—but I have considered him to be the most genuinely principled man to hold that office in my lifetime. I don't want to start a debate here about the Shah, Nicaragua, the hostage crisis, thermostats, or the Panama Canal, but anyone who looks at Carter's life to-date must come away with the impression of a good and decent man. The work he's done post-presidency, through the Carter Center, through Habitat for Humanity, has transformed untold lives here, and abroad.

Plains, Georgia is quaint, and the National Historic Site is scattered in and around the town. There's the train depot, which was campaign headquarters in 1976. There's Billy's gas station. Outside of town is the boyhood farm, where you can peer into young Jimmy's bedroom. The old high school is the Visitor Center. A film is shown in the classic auditorium, where Jimmy and future wife Rosalynn were called to daily assemblies (assemblies including prayer in those days). The hallways and classrooms of the high school are devoted to exhibits of the Carters' lives, from childhood, to the White House, and beyond.

|

| Jimmy feeding a colt on the farm [from the NPS website] |

The early lives of our presidents have always fascinated me, and Carter's story is uniquely, quintessentially American. I was so moved by the book, and a life well lived, that when I finished reading I penned a letter to the former president. It's the very first time I've written to an erstwhile Leader of the Free World, and I naturally had no expectation that he would ever read it. I complimented him on his book, and the important work he's done.

One thing in particular I was curious about was whether people growing up in Plains, and Americus, in the 20's and 30's—particularly school children—ever heard about the notorious Civil War prison down the road at Andersonville (MacKinlay Kantor's Pulitzer Prize-winning novel, Andersonville, was not published till 1955). Was it spoken of in polite company? Was there a local version of events to account for it? I mailed my letter to Jimmy Carter on May 14.

Astonishingly, on July 2 I received a letter back, the original of mine in the margin of which Mr. Carter scribbled a note. I got my answer and I'm satisfied with it.

Saturday, June 29, 2013

When I think baseball, I think Custer bobblehead

The first 1,000 fans through the turnstile at tonight's Hagerstown, Maryland Suns game (Class A farm team for the Washington Nationals), get to take home a George Custer bobblehead. It seems a peculiar choice, but not to Hagerstown Visitor's Bureau president Thomas Riford, who calls Custer a "folk hero" in those parts. The promotion is not being well received by the staff and readers of Indian Country Today.

Tuesday, June 25, 2013

Prison Times, volume one, number one

From Slate.com's, "The Vault," comes this rare gem:

"Confederate prisoners of war confined at Fort Delaware produced this newspaper by hand in 1865. The New York Historical Society holds one of four surviving copies, each of which was likely passed around and read by multiple prisoners. The paper numbers four pages in total."

"Confederate prisoners of war confined at Fort Delaware produced this newspaper by hand in 1865. The New York Historical Society holds one of four surviving copies, each of which was likely passed around and read by multiple prisoners. The paper numbers four pages in total."

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)