[Photo by Wesley A. Leiser]

[Photo by Wesley A. Leiser]

I have periodically mulled over the idea of writing a biography of one or another lesser-known or less celebrated Civil War notable. Like a lot of people with an unnatural fixation on the literature of the Civil War, I have spent time thinking about how to make my lasting contribution, how to make my mark, and that invariably leads one to try to discern the gaps on the bookshelf — to try to imagine what's left undone.

For one thing, I think about peripheral, roughly-treated, or short-shrifted officers, and there's no shortage in those categories. I narrow it down further by focusing on characters who had some impact before or after the war in California, because it melds periods of interest for me, and connects them to the geography I live in and love. I mull these biographies at least seriously enough to collect bits and pieces of information along the way, and to record little reminders to myself to mine less obvious sources. I think about people like Frederick Steele, because he is buried not far from my home, because he engaged in operations in areas that hold fascination for me (e.g., Trans-Mississippi), and because his papers are at Stanford. And I think about Irvin McDowell, who came to San Francisco during the war, and who returned later and made part of his legacy an enduring contribution to one of America's great urban open spaces, Golden Gate Park.

Dimitri Rotov's blog entry today, castigating Carol Bundy for sloppy errors in Nature of Sacrifice [see additional comments below], noted the lack of a McDowell bio. And like a breath on a dying ember, the McDowell reference prompted in me a wistful flare-up of the excitement and dread that surrounds a project that needs doing, and one that inspires more conviction than commitment. McDowell played an important role in the war, and he deserves better than the snide remarks one encounters so frequently in the works of armchair generals, or in the "best" and "worst" lists of buffs, and weekend warriors. I'm reminded of another Dimitri offering, addressing this very point about generals like McDowell, and Nathaniel Banks, men who became cardboard cutouts in the recounting, their long lives of distinction discounted because of the fortunes of war in their short times on stage.

"Honest patriots struggling with their own limitations in trying circumstances at the bottom of the red hot crucible of war are to be dressed in jester's costumes and showered with scorn: the Popes, the McClellans, the Buells, the political generals, the failures. You are invited to hiss at them."

"Commisary Banks," under any other criteria than his generalship in Virginia and Louisiana, has to be regarded as an exceptionally successful and interesting man. But to those who view the four years of the Civil War as a lifetime, Banks is the object of casual ridicule.

McDowell doesn't need a biography to settle the score, or to rehabilitate his image. He just needs one to capture his life as a man, and to present an indifferent appraisal of his Civil War service. Irvin answered the call. He served his country faithfully and well, the chaotic collapse of his green troops at Bull Run notwithstanding. At the very least, we should start by spelling his first name correctly on his tombstone. Cue Rodney Dangerfield punchline.

Getting back to Bundy's biography of Charles Russell Lowell, Jr., this was the subject of quite a bit of discussion in The Civil War Forum last August. What started as a guardedly complimentary appraisal quickly turned into a laundry list of embarrassing errors, as more readers chimed in. Steve Meserve, for example, commented on Bundy's characterization of California governor Leland Stanford as a "copperhead." In fact he was a staunch Unionist and Lincoln man all the way, who campaigned for Lincoln. Nearly everyone who reads this book, apparently, finds something glaringly erroneous. I guess I'll settle for the book reviews.

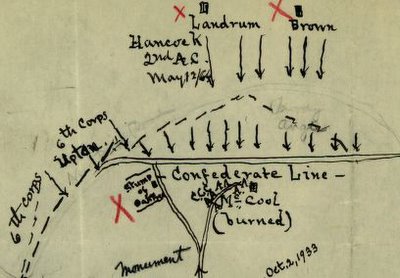

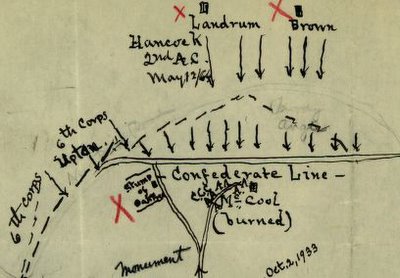

Map: Spotsylvania Court House. This detail of a hand-drawn map shows the location of the Confederate line and the location of Union troops, including the 6th Corps under Upton and 2nd under Hancock; and also the spot where Stonewall Jackson's amputated arm was buried. Robert Goldthwaite Carter papers, 1900-1934 (Mss2 C2467 b) Manuscripts. Library of Congress.

Map: Spotsylvania Court House. This detail of a hand-drawn map shows the location of the Confederate line and the location of Union troops, including the 6th Corps under Upton and 2nd under Hancock; and also the spot where Stonewall Jackson's amputated arm was buried. Robert Goldthwaite Carter papers, 1900-1934 (Mss2 C2467 b) Manuscripts. Library of Congress.

I like reading book reviews. I like studying atlases. Imagine my delight when I came across a book review of Civil War atlases. This popped up recently on the Civil War Book Review web site, covering six ― count 'em six ― Civil War atlases.

The Visualization of Cartographic Information: A Review Essay of Six Civil War Atlases by Hardy, Jr. James D. and Hochberg, Leonard J. [CWBR Issue: Winter 2006]

Books under consideration:

The Official Military Atlas of the Civil War: Atlas to Accompany the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, George B. Davis, Major, U. S. Army; Leslie J. Perry; Joseph W. Kirkley; Calvin D. Cowles, Captain, U. S. Army. Richard Sommers, introduction. Washington, 1891-1895; New York, 1983, 2003 Government Printing Office; Arno Press; Barnes and Noble

Maps of the Civil War: The Roads They Took, David Phillips

New York, 1998, 2001, Metro Books, Friedman/Fairfax

Atlas of the American Civil War: The West Point Military History Series, Thomas E. Griess, Series Editor, Garden City, New York, 2002, Square One Books

Atlas of the Civil War: Month by Month, Major Battles and Troop Movements, Mark Swanson, Athens, Georgia and London, 2004, University of Georgia Press

Great Maps of the Civil War: Pivotal Battles and Campaigns, Featuring 32 Removable Maps. William Miller, Rod Gragg, foreword and additional text, Nashville, Tennessee, 2004, Rutledge Hill Press, Thomas Nelson Publishers

Atlas of the Civil War, Steven E. Wadsworth and Kenneth J. Winkle, James M. McPherson, forward and introduction, Oxford, New York, 2004, Oxford University Press

How unusual, these days, that an author or team of authors find a vein to mine that is so rich and undisturbed, the resulting scholarship can be considered to have broken new ground in the super-saturated world of Civil War historiography. That's just what Dr. Thomas Lowry and his wife Beverly, and Jack Welsh on one title, have done with the court-martial records in the National Archives. Maybe no one thought anything interesting could be found in the accounts of military legal proceedings. Maybe Jack Nicholson was speaking to timid researchers when he bellowed, "You Can't Handle the Truth!" And maybe some authors found the chaotic disorganization of the courts-martial documentation too daunting to delve into.

How unusual, these days, that an author or team of authors find a vein to mine that is so rich and undisturbed, the resulting scholarship can be considered to have broken new ground in the super-saturated world of Civil War historiography. That's just what Dr. Thomas Lowry and his wife Beverly, and Jack Welsh on one title, have done with the court-martial records in the National Archives. Maybe no one thought anything interesting could be found in the accounts of military legal proceedings. Maybe Jack Nicholson was speaking to timid researchers when he bellowed, "You Can't Handle the Truth!" And maybe some authors found the chaotic disorganization of the courts-martial documentation too daunting to delve into.

But thank goodness the Lowrys gave it a stab. Handwritten documents for roughly 80,000 Union court-martials (on paper of varying color and size, depending on what was available at the time) reside in a series of numbered manila folders comprising Record Group 153. They are, Dr. Lowry explains, in no particular order other than "vaguely chronological." One folder might contain a single court-martial, or dozens. Pages for a given court-martial were collected together with a ribbon, or paste, or a metal clip, now disintegrating into rust. Lowry notes that some of the unnumbered, gathered pages have been "disassembled, producing a 'paper salad,' with pages out of order." The only guide is an 1885 name index, but to Thomas and Beverly's everlasting credit, they are creating a useable subject index. Sadly, most Confederate transcripts of court-martial proceedings were burned up in the conflagration in Richmond at the close of the war. Two famous examples survive, as Robert K. Krick explains in an introduction to one of Lowry's books: "the ineffectual hounding of General Richard Brooke Garnett" by 'Stonewall' Jackson after Kernstown, and Longstreet's charges against Lafayette McLaws following events at Knoxville. "Court-martial" frequently translates to "very colorful story."

Lowry's books aren't dry recitations of harsh proceedings, as this material might have been presented in lesser hands. They are riveting tales, told efficiently and intelligently, threaded throughout with a wit worthy of the subject matter. You've read about the exploits that made men famous. For every one of those, there are two or three whose exploits made them infamous, just not in ways their descendants necessarily celebrate. Erstwhile professor of psychiatry, graduate of Stanford Medical School and veteran of the Kinsey Institute, Lowry first made a splash in Civil War circles with The Story the Soldiers Wouldn't Tell: Sex in the Civil War (1994). Discerning readers might have been guarded at first (was he using "sex" in the title in the same cynical marketing fashion that some people use "Gettysburg"?). No, turns out it was book of "fresh" research, shocking in the way it detailed things that should have been well known, but which were, in fact, unheard of. Or, unspoken of. It is a rich vein, as I mentioned at top.

Lowry's books aren't dry recitations of harsh proceedings, as this material might have been presented in lesser hands. They are riveting tales, told efficiently and intelligently, threaded throughout with a wit worthy of the subject matter. You've read about the exploits that made men famous. For every one of those, there are two or three whose exploits made them infamous, just not in ways their descendants necessarily celebrate. Erstwhile professor of psychiatry, graduate of Stanford Medical School and veteran of the Kinsey Institute, Lowry first made a splash in Civil War circles with The Story the Soldiers Wouldn't Tell: Sex in the Civil War (1994). Discerning readers might have been guarded at first (was he using "sex" in the title in the same cynical marketing fashion that some people use "Gettysburg"?). No, turns out it was book of "fresh" research, shocking in the way it detailed things that should have been well known, but which were, in fact, unheard of. Or, unspoken of. It is a rich vein, as I mentioned at top.

In 1997 Lowry followed up the Sex book with Tarnished Eagles: The Courts-Martial of Fifty Union Colonels and Lieutenant Colonels (the "eagle" referring to a colonel's insignia). Not so sexy, but even more colorful. The year 2000 saw the release of Tarnished Scalpels: The Court-Martials of Fifty Union Surgeons. Alert readers and anal retentive editors will note the Stackpole dust jacket designer quandary between "court-martials" and "courts-martial." Glad I wasn't there for that, but I think you have to go with the plural "courts-martial" in both instances. Kudos to Stackpole for publishing Lowry's work, these and other titles, which all still look to be available if you search Stackpole's site under author or title name.

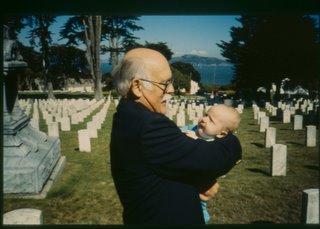

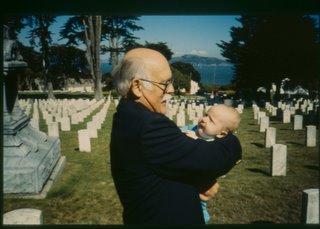

Dr. Lowry with my newborn son Atticus, Presidio National

Cemetery, San Francisco, circa 1994.

According to Neil Young in interviews here, and elsewhere, when recording the hymn-like final tune on his new album Prairie Wind — a song conspicuously out of place amidst the other compositions, and about which Young said, "I'd never written a song like this before" — he paused to wonder aloud about where this particular muse had come from. One of the studio engineers grabbed a flashlight, signaled Young to follow, removed a part of the modern ceiling and shined the light high into the dark space above, revealing the great arched windows of a very old church. Young, who wrote the song in the studio and was unaware of the building's history, got "goosebumps" as the light illuminated the hidden history of the walls around him.

This church is on 17th Street South in Nashville, and a facade hides the historic structure's original exterior. It was a church before and after the Civil War, and before the Federal army seized the capital it was a Confederate hospital, and morgue. I'm trying to find out if Mark Zimmerman, author of Guide to Civil War Nashville, knows anything about it. The building is most famous as the original Monument Studios (now Masterlink), where Roy Orbison, for one, recorded all his hits, and where Young himself recorded Comes a Time, and his masterpiece, Harvest.

Young is sensitive to history, now more than ever, and spoke of organizing a group to restore the old church while maintaining it's equally historic studio. Time was (and probably still), some in the South bore a grudge against Young for "Southern Man," and "Alabama," powerful, enduring songs that prompted one of Rock and Roll's most lame rejoinders in "Sweet Home Alabama."

Times change. Alabama is different, I suspect. And Neil Young is now the Old Man he once sang to. But this old man has Hank Williams's guitar.

Speaking of Nashville, there are still eight seats left on The Bus for next month's Civil War tours of Franklin, and Nashville. Masterlink Studios is not on the itinerary, but you might find time to drive by while you're there.

Young is sensitive to history, now more than ever, and spoke of organizing a group to restore the old church while maintaining it's equally historic studio. Time was (and probably still), some in the South bore a grudge against Young for "Southern Man," and "Alabama," powerful, enduring songs that prompted one of Rock and Roll's most lame rejoinders in "Sweet Home Alabama."

Times change. Alabama is different, I suspect. And Neil Young is now the Old Man he once sang to. But this old man has Hank Williams's guitar.

Speaking of Nashville, there are still eight seats left on The Bus for next month's Civil War tours of Franklin, and Nashville. Masterlink Studios is not on the itinerary, but you might find time to drive by while you're there.

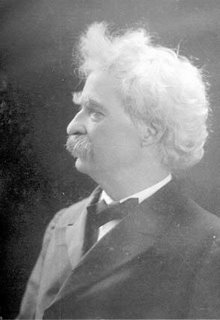

You can read regimental histories, campaign analysis, letters, diaries, and the Official Records till the end of time, but there's a conspicuous gap in your studies if you've never read Mark Twain's account of his Civil War service. The good news is that it's only a click away, online here, and other places. The passage below gives you the flavor of the story. Here, the young volunteer and his fellow recruits, content in camp, learn that the enemy is headed their way:

You can read regimental histories, campaign analysis, letters, diaries, and the Official Records till the end of time, but there's a conspicuous gap in your studies if you've never read Mark Twain's account of his Civil War service. The good news is that it's only a click away, online here, and other places. The passage below gives you the flavor of the story. Here, the young volunteer and his fellow recruits, content in camp, learn that the enemy is headed their way:

For a time, life was idly delicious. It was perfect. There was no war to mar it. Then came some farmers with an alarm one day. They said it was rumoured that the enemy were advancing in our direction from over Hyde's prairie. The result was a sharp stir among us and general consternation. It was a rude awakening from our pleasant trance. The rumour was but a rumour, nothing definite about it, so in the confusion we did not know which way to retreat. Lyman was not for retreating at all in these uncertain circumstances but he found that if he tried to maintain that attitude he would fare badly, for the command were in no humour to put up with insubordination. SO he yielded the point and called a council of war, to consist of himself and three other officers, but the privates made such a fuss about being left out we had to allow them to remain, for they were already present and doing most of the talking too. The question was, which way to retreat; but all were so flurried that nobody even seemed to have even a guess to offer. Except Lyman. He explained in a few calm words, that inasmuch as the enemy were approaching from over Hyde's prairie our course was simple. All we had to do was not retreat toward him, another direction would suit our purposes perfectly. Everybody saw in a moment how true this was and how wise, so Lyman got a great many compliments. It was now decided that we should fall back on Mason's farm.

[Photo by Wesley A. Leiser]

[Photo by Wesley A. Leiser]