—Pete Townshend

—Pete Townshend

Take the Greek "pan," for "all," and stick it on "horama," meaning view, and you get panorama. So says Nicole, and with a smile that confident, I'm just going to take her word for it.

One of the most amazing things about the internet these days is unfettered access to photo collections at various repositories. I can get swept away for hours just randoming searching the digital offerings at the Library of Congress. This evening I got lost in the Panoramic Photograph Collection. Initially I was looking to see what they had in the way of panoramic Civil War images (the key words "civil war" will bring up 33 hits), and there are some good ones, particularly covering Gettysburg and Vicksburg, taken mostly in the early 1900s. The view at top is of the Round Tops at Gettysburg. It's worth visiting the site and viewing the images at full size (click on the image here, then click on it again at the LoC site to expand the view). To find other Civil War images, start at the PPC home page, and be sure to use the "search this collection" as opposed to the "search all collections" box, to restrict your search to the panoramas.

The breadth of what they're offering online is pretty impressive, though presumably a fraction of their holdings. The Panoramic Photograph Collection has some 4,000 images "featuring American cityscapes, landscapes, and group portraits." I spent about 90 minutes just searching for different places I've lived, and finding some stunning views I'd never come across before. One example: I lived in Evansville, Indiana for six years, and the riverfront—where downtown edges up to the broad sweep of the mighty Ohio—was one of my favorite places. There's just something about a big old river. It was there before cameras, and buildings, and it will be there after. I was happy to find this view of that oft-visited spot.

It is absolutely mesmerizing to see a frozen moment in time, of a very familiar place, but populated with people and buildings lifetimes removed from your own experience. The panoramic view has the effect of breathing more life into the scene, and the old black and white, grainy quality accentuates the feeling that one is looking through a mysterious window into the past.

I want to mention another site that's been around quite awhile, in case you're not already familiar with it, or you didn't have the processing power to tackle it on first encounter.  Adding some modern technology to panoramic views, the folks at Behind the Stonewall have produced over one-hundred 360-degree panoramic videos on Civil War battlefields (stitching together still snapshots into spinning images that can be controlled—left or right, slow or fast—with your mouse). They cover a number of battlefields to-date, and give especially good coverage to Gettysburg, Manassas, Antietam, and Chickamauga, where the various panoramas are keyed to a map. The view window is small, but the images are sharp—still not recommended for dial-up, I'm guessing. I would like to give encouragement to sites like this one, which use the internet in creative, useful, and magnamimous

Adding some modern technology to panoramic views, the folks at Behind the Stonewall have produced over one-hundred 360-degree panoramic videos on Civil War battlefields (stitching together still snapshots into spinning images that can be controlled—left or right, slow or fast—with your mouse). They cover a number of battlefields to-date, and give especially good coverage to Gettysburg, Manassas, Antietam, and Chickamauga, where the various panoramas are keyed to a map. The view window is small, but the images are sharp—still not recommended for dial-up, I'm guessing. I would like to give encouragement to sites like this one, which use the internet in creative, useful, and magnamimous

ways.

Below: written on front: "[Copyright] 1912, S.U. Bunnell, Pasadena, Cal., Largest trees on Earth series, #572."

One often reads that Civil War soldiers were the most literate in our history, a fact attested to by the voluminous letters, diaries, and reminiscences penned by participants, many of which are available to us in some published form, or preserved in various archives and repositories. Caches of soldier letters and previously unseen diaries routinely surface even today, and every Civil War publisher, I would wager, has a number of proposals in the hopper right now for previously unpublished material. So common are Civil War letters and diaries that publishers, thank goodness, are more discriminating than they used to be. The University of Tennessee Press' Voices of the Civil War series, under the masterful guidance of series editor Pete Carmichael, is as good as it gets in that department.

One also reads that the Civil War was the last in which soldiers' letters home were uncensored by the military. I'm not sure how true that is—whether, for instance, letters home in the Spanish American War were censored—but certainly by WWI the army was cutting or blacking out certain references (I have a stack of letters that my grandfather wrote in WWI that were too innocuous to be edited, but bear the stamp of the censor's approval).

In some ways, with the current U.S. deployments in Afghanistan and Iraq, we are harkening back to something akin to the Civil War era—we have a highly literate soldiery with nearly unfettered channels to communicate their experiences to the citizenry back home. During the Civil War, some soldiers acted as war correspondents for their hometown paper. Today, soldiers in Iraq and Afghanistan have the internet—email and blogging—with unlimited readership.

In recent weeks, some of my fellow (Civil War) bloggers have been announcing the discovery or appearance of a flurry of Civil War blogs, and I would welcome them too, but can't keep up with them all. Instead, I wanted to make mention of a blog that has kept me mesmerized and riveted for weeks now—The Sandbox—with it's well-written, moving insights, alternately horrific, funny, deeply touching, or pins-and-needles suspenseful, from the latest generation of Americans at the front.

You can't stop reading this stuff. Nor should you.

Some book reviews are so harsh, so thoroughly biting and dripping with such disdain, you figure either the reviewer has peeled away all of a book's pretense and exposed the fraudulent core to sunlight, or else it's personal—maybe the author stole money from the reviewer at some point in the past, or treated his sister poorly. I'm not sure which is the case with Stephen Metcalf's scathing assault on Thirteen Moons, the new novel by Charles Frazier. He takes Frazier to task for "bad faith" with the reader, a damning indictment, indeed.

Reviewing fiction is a tricky thing, subjective by definition—subject to wildly varying tastes and points of reference. We all have favorite novels that have been both praised and panned. Because of the marketing machine behind Frazier's new release, we can already find an assortment of reviews from major outlets. I read three in the first week, including a so-so critique at Salon.com, and a generally positive endorsement in the San Francisco Chronicle.

Reviewing non-fiction is another matter. The work is still subject to the reviewer's personal perspective, but things like accuracy and organization weigh heavily in the analysis. Some reviewers have vendettas, apparently, but generally speaking, a good reviewer who skewers a work of non-fiction does so with the spirit of a faithful guard dog, whose loud growls tip off the reader that his time and money are best spent elsewhere. Fangs are also bared to serve notice that a particular work does not deserve to share shelf space with worthwhile Civil War books. Sometimes the skewering is simply the natural response to being insulted as a reader, and consumer.

The expanding Civil War market of the 80s and 90s (now rapidly fading), and the advent of myriad self-publishing options and vanity presses, has kept the guard dogs busy. I should have mentioned at top that critiquing a book is a solemn endeavor, and just as surely as there are poor authors, there are poor reviewers, ill-equipped for the task, who do the reader and the author a disservice.

That said, few things are as satisfying to read or write as the authoratative annihilation of a piece of crap passing itself off as a work of serious scholarship. I wish I could find an old clipping I had from The Civil War News, many years ago, of a Richard McMurry review of The South Was Right, by Kennedy & Kennedy. It was deliciously dismissive of one of the worst books ever written on the subject, with all of the sarcasm and wit that has garnered McMurry fans and detractors for decades.

When I started this blog entry, I intended to spend some time musing about the responsibility (obligations) of the book reviewer, and where the best (Civil War) reviews might be found—things I've spent some time thinking about as a former book review editor, and occasional reviewer myself. I have long loved the book review sections of newspapers, magazines, newsletters, and such. The right reviewer for the right book makes for a great essay, smart and informative. Everything I know about some subjects, I read in the Sunday book review section.

But I've rambled enough for tonight, and will weigh in on the subject in a more focused way later, if I can think of a way to do it without sounding like a pompous ass. This entry made mention of skillful skewerings of a work of fiction that might not have deserved it, and a work of non-fiction that fairly begged for the coup de grace. But there's more to the art of critiquing Civil War studies than shish kebab. Sometimes just an honest overview, with commentary on the bibliograpy, suffices.

Some book reviews are so harsh, so thoroughly biting and dripping with such disdain, you figure either the reviewer has peeled away all of a book's pretense and exposed the fraudulent core to sunlight, or else it's personal—maybe the author stole money from the reviewer at some point in the past, or treated his sister poorly. I'm not sure which is the case with Stephen Metcalf's scathing assault on Thirteen Moons, the new novel by Charles Frazier. He takes Frazier to task for "bad faith" with the reader, a damning indictment, indeed.

Reviewing fiction is a tricky thing, subjective by definition—subject to wildly varying tastes and points of reference. We all have favorite novels that have been both praised and panned. Because of the marketing machine behind Frazier's new release, we can already find an assortment of reviews from major outlets. I read three in the first week, including a so-so critique at Salon.com, and a generally positive endorsement in the San Francisco Chronicle.

Reviewing non-fiction is another matter. The work is still subject to the reviewer's personal perspective, but things like accuracy and organization weigh heavily in the analysis. Some reviewers have vendettas, apparently, but generally speaking, a good reviewer who skewers a work of non-fiction does so with the spirit of a faithful guard dog, whose loud growls tip off the reader that his time and money are best spent elsewhere. Fangs are also bared to serve notice that a particular work does not deserve to share shelf space with worthwhile Civil War books. Sometimes the skewering is simply the natural response to being insulted as a reader, and consumer.

The expanding Civil War market of the 80s and 90s (now rapidly fading), and the advent of myriad self-publishing options and vanity presses, has kept the guard dogs busy. I should have mentioned at top that critiquing a book is a solemn endeavor, and just as surely as there are poor authors, there are poor reviewers, ill-equipped for the task, who do the reader and the author a disservice.

That said, few things are as satisfying to read or write as the authoratative annihilation of a piece of crap passing itself off as a work of serious scholarship. I wish I could find an old clipping I had from The Civil War News, many years ago, of a Richard McMurry review of The South Was Right, by Kennedy & Kennedy. It was deliciously dismissive of one of the worst books ever written on the subject, with all of the sarcasm and wit that has garnered McMurry fans and detractors for decades.

When I started this blog entry, I intended to spend some time musing about the responsibility (obligations) of the book reviewer, and where the best (Civil War) reviews might be found—things I've spent some time thinking about as a former book review editor, and occasional reviewer myself. I have long loved the book review sections of newspapers, magazines, newsletters, and such. The right reviewer for the right book makes for a great essay, smart and informative. Everything I know about some subjects, I read in the Sunday book review section.

But I've rambled enough for tonight, and will weigh in on the subject in a more focused way later, if I can think of a way to do it without sounding like a pompous ass. This entry made mention of skillful skewerings of a work of fiction that might not have deserved it, and a work of non-fiction that fairly begged for the coup de grace. But there's more to the art of critiquing Civil War studies than shish kebab. Sometimes just an honest overview, with commentary on the bibliograpy, suffices.

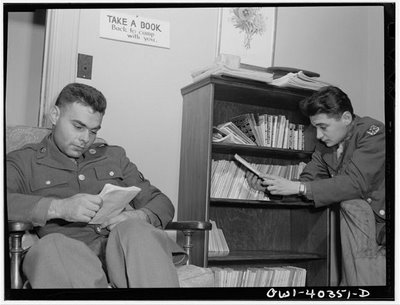

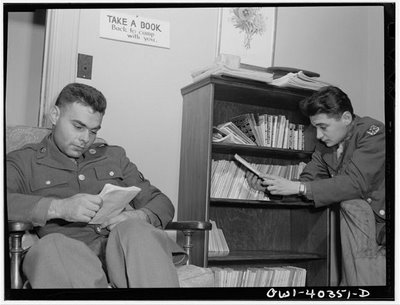

Photo: Washington, D.C. In the library at the United Nations service center. Boys are urged to take books back to camp with them. Bubley, Esther, photographer. 1943 Dec.

[Photo: "People escaping from the Indian massacre, at dinner on a prairie," Library of Congress, details below]

It's well nigh impossible for people today to conceive of how chaotic and unsettling things must have looked in the 2nd year of the war. All of the enthusiasm for a quick victory, and the anxiety of young men deeply worried that the war would end before they had a chance to participate, was played out and spent in desperate, gory killing fields that had nothing of romance or glory about them.

[Photo: "People escaping from the Indian massacre, at dinner on a prairie," Library of Congress, details below]

It's well nigh impossible for people today to conceive of how chaotic and unsettling things must have looked in the 2nd year of the war. All of the enthusiasm for a quick victory, and the anxiety of young men deeply worried that the war would end before they had a chance to participate, was played out and spent in desperate, gory killing fields that had nothing of romance or glory about them.

HIGH TIDE

In April, at Shiloh—to cite an oft-repeated statistic—casualties in the 2-day battle exceeded the combined casualties for Americans in all previous wars (Mexican War, War of 1812, Revolution). In September, casualties at Antietam remain the single highest one-day total in American history. In 1862, the real "high tide" of the Confederacy swelled, and fell back, in all theaters of the war. It was the only year that Confederate armies made major offensive incursions across the board. The Confederate invasion of New Mexico fell short at Glorieta Pass in the Far West; in the Trans-Mississippi, Van Dorn's designs on St. Louis were thwarted at Pea Ridge in the Boston Mountains of NW Arkansas; in the Western Theater, Bragg's movement with the Army of Tennessee surged as far north as Perryville, Kentucky, before the great southward ebb; in the East, Lee's first invasion across the Potomac ended in stalemate at Sharpsburg. Add to all that Jackson's Shenandoah Valley Campaign, the slaughter of the Seven Days on the Peninsula, and another, far-bloodier battle along Bull Run, and surely for many, the erstwhile, gung-ho sense of adventure dissolved into an uneasy feeling of apocalyptic dread.

DARK STAINS

If epic battles weren't enough, the close of 1862 was marked by a series of mass executions, signaling that whatever business was afoot in these disunited states, it was not business as usual. In a span of roughly 10 weeks, between mid-October and the day after Christmas, 1862, at least 60 people were executed—some in summary fashion, the rest after trials of a sort, but none in a way that makes anyone beam with pride today.

Most famous, perhaps, was the execution of 38 Sioux Indians on December 26, in Mankato, Minnesota, in the aftermath of the Sioux uprising there. Lincoln, to his credit, commuted the death sentences of over 250 Sioux, but the mass hanging remains the largest in U.S. history. The "Palmyra Massacre," in Palmyra, Missouri on October 18, was a simple case of murder. On that day, ten Confederate prisoners were ordered shot in an act of cold-blooded retaliation.

Less well known is the Great Hanging at Gainesville, Texas, also in October. There, 40 citizens thought to be overly sympathetic to Union war aims were executed (two others were reportedly shot while attempting to flee). It's a chilling thing to contemplate, and but for the scale, not unlike the internecine bloodshed already well advanced in Kansas, Missouri, East Tennessee, and other places.

Dark chapters, all, and all have been written about with varying degrees of success. For the latter event, most easily accessible is Tainted Breeze, by Richard B. McCaslin.

Lots of things have been written on the Sioux War in Minnesota—I still like an old (1961) booklet by Kenneth Carley, put out by the Minnesota Historical Society.

I'm not sure what might be reliable with respect to the Palmyra killings, though accounts of the event are included in any number of texts on the Trans-Mississippi. One can see the mass grave of the victims here.

[Photo at top by Adrian J. Ebell, created or published August 21, 1862. Library of Congress summary reads, “A Group of men, women, and children rest and eat during their flight from Fort Ridgely, Minnesota during the Native American Sioux uprising. Stephen R. Riggs sits near a woman who stands by a wagon." See image here.]

—Pete Townshend

—Pete Townshend

Adding some modern technology to panoramic views, the folks at Behind the Stonewall have produced over one-hundred 360-degree panoramic videos on Civil War battlefields (stitching together still snapshots into spinning images that can be controlled—left or right, slow or fast—with your mouse). They cover a number of battlefields to-date, and give especially good coverage to Gettysburg, Manassas, Antietam, and Chickamauga, where the various panoramas are keyed to a map. The view window is small, but the images are sharp—still not recommended for dial-up, I'm guessing. I would like to give encouragement to sites like this one, which use the internet in creative, useful, and magnamimous

Adding some modern technology to panoramic views, the folks at Behind the Stonewall have produced over one-hundred 360-degree panoramic videos on Civil War battlefields (stitching together still snapshots into spinning images that can be controlled—left or right, slow or fast—with your mouse). They cover a number of battlefields to-date, and give especially good coverage to Gettysburg, Manassas, Antietam, and Chickamauga, where the various panoramas are keyed to a map. The view window is small, but the images are sharp—still not recommended for dial-up, I'm guessing. I would like to give encouragement to sites like this one, which use the internet in creative, useful, and magnamimous