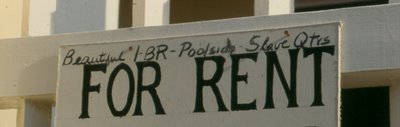

Poolside slave quarters. And "beautiful" to boot.

Poolside slave quarters. And "beautiful" to boot.I took this photo in 1988 on my one and only visit to New Orleans, where my sister was living at the time. First visit, I should say, since our family moved away from New Orleans when I was very small.

What an intriguing city ― and what a heart-rending tragedy that befell her in 2005. Among other things, I took in some Civil War sites: Confederate Memorial Hall (just reopened) which claims to have "the second largest collection of Confederate memorabilia in the world in the oldest continually operating museum in Louisiana"; Metairie Cemetery; a house once belonging to Pierre Gustave Toutant Beauregard. . .

New Orleans is so infused with its own unique history ― its own original culture ― one can't help but be fascinated, or seduced. The religion, food, music, language, none of it reminds you of Dubuque. Same river, different feedcaps.

The city has seen some changes since slaves lived in this now-desirable, 1-bedroom unit in the French Quarter. Fewer slaves, more pools, for one thing. Thank goodness the Quarter was spared. New Orleans is a city apart, a melting pot unto itself. The soul of the city will be revived, in time.

The river rose all day

The river rose all night

Some people got lost in the flood

Some people got away alright

The river have busted through cleard down to Plaquemines

Six feet of water in the streets of Evangeline

(Randy Newman, Louisiana 1927)

The river rose all night

Some people got lost in the flood

Some people got away alright

The river have busted through cleard down to Plaquemines

Six feet of water in the streets of Evangeline

(Randy Newman, Louisiana 1927)