So goes the opening line to the preface of Edward L. Ayers book, What Caused the Civil War? Reflections on the South and Southern History. What follows is a thoughtful—and readable!—series of essays by a "professional historian who is both a native and a longtime resident of the South" endeavoring to understand the region. The opening passage of the essay of the same name (minus the subtitle) gets to the heart of the matter in a language we can understand, which is to say the language of Matt Groening:

So goes the opening line to the preface of Edward L. Ayers book, What Caused the Civil War? Reflections on the South and Southern History. What follows is a thoughtful—and readable!—series of essays by a "professional historian who is both a native and a longtime resident of the South" endeavoring to understand the region. The opening passage of the essay of the same name (minus the subtitle) gets to the heart of the matter in a language we can understand, which is to say the language of Matt Groening:

On The Simpsons, a popular animated satire of American life, Apu Nahasapeemapetilan, an industrious South Asian immigrant in Springfield, U.S.A., has studied hard for his citizenship test. "What was the cause of the Civil War?" is the final question on the oral quiz. "Actually, there were numerous causes," says Apu. "Aside from the obvious schism between the abolitionists and the anti-abolitionists, there were economic factors, both domestic and inter—" The official, clearly bored with such superfluous erudition, intones flatly: "Just say slavery." Apu eagerly concedes the point: "Slavery it is, sir." With this declaration Apu wins his citizenship. Why is this funny? It's not because slavery was not the cause of the Civil War, but because the bureaucrat demands a rote answer to explain a profoundly complex problem at the center of the nation's experience.

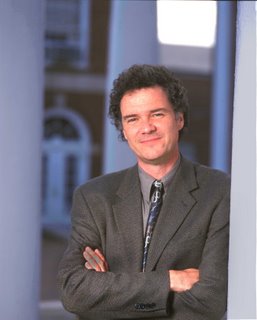

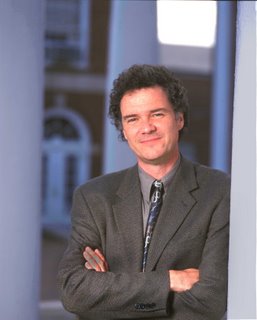

Professor Ayers will be the guest in the next Civil War Forum Conference Series, a one-hour Q&A session on October 7 at 4:00 p.m. EST in the Forum's "Room 1." He'll be on hand to discuss his various Civil War-related titles, and innovative work with the Valley of the Shadow web site. He is the Dean of the College and Graduate School of Arts and Sciences at the University of Virginia. Whenever I want a reminder of how little I accomplished in my squandered youth, I'll take a glance at Ayers's biblio, C.V., etc., at the university's web site.

Mark your calendars.

—tracing the Far West footprints of Civil Warriors

—tracing the Far West footprints of Civil Warriors

A couple of weeks ago we returned from another glorious camping trip in secesh country. No, not THAT secesh country, the other one, the lava-strewn State of Jefferson. Also known as the 51st state. I caught a brown trout for the first time in my life, though in truth, it more or less caught itself, as I found it on the end of the line after leaving my pole unattended for an hour or two. That counts.

My very first entry in this blog made mention of last summer's camping trip up near the Lava Beds National Monument, where one can see the site of the death of E. R. S. Canby, the first and only U.S. Army general officer killed in the nation's various Indian wars. He was murdered—shot and killed at close range during a peace conference. It never occurred to me until I was typing this, but ironically, Jefferson C. Davis —who, during the Civil War, likewise put a general in his grave—eventually took command of the troops after the demise of Canby.

Alex Trabek, take note—I have a good one for you: “Indian Wars for a $1,000: At one point in this war, opposing forces were each commanded by a leader who had personally shot and killed a general in the United States Army.” . . . “What is The Modoc War of 1873?” [a Jeff Davis aside: on one of my first visits to the Presidio Officer's Club in San Francisco, now a jewel in the National Park Service, I was studying a post-Civil War group photo of officers stationed there, and a docent or secretary pointed to one of the figures in the photo, drawing my attention to Jefferson C. Davis—one of Uncle Billy's corps commanders—whom she identified, in the proud way that curators discuss historic connections, as "the president of the Confederacy, Jefferson Davis." I had long had an interest in this Hoosier officer, as my wife had ancestors in Jefferson C. Davis's 22nd Indiana—his imposing visage is unmistakable. But I was raised too well by my mother to correct my host, who had a better story than the one I would have told. No harm, no foul.]

But enough of Jefferson Davis, and the State of Jefferson. Departing the wilds of Northern California, we split up the long drive back to the Bay Area with a stopover in Clear Lake, down in Lake County. I've mentioned before that a Civil War buff living in the Far West is forever crossing pre- and post-war paths with Civil War notables, something that helps flesh out one's perspective of those whom we too often think of only in the context of their brief Civil War careers.

Photo at right: Clear Lake from our hotel balcony.  One of those well-traveled officers, Capt. Nathaniel Lyon of the 1st Dragoons, marched to the Clear Lake area in May of 1850, just months before California was admitted to the Union as the 31st state. He stayed in the vicinity long enough to cause an otherwise non-descript eminence to be forever after referred to as "Bloody Island." I had never heard of it before, but everything I've been able to turn up in the weeks since describes the "Battle of Bloody Island," or the Bloody Island/Clear Lake Massacre in horrific terms—a bad day for the Pomo however you reconcile the widely varying casualty counts. Another description, and photo of the "island" is here.

One of those well-traveled officers, Capt. Nathaniel Lyon of the 1st Dragoons, marched to the Clear Lake area in May of 1850, just months before California was admitted to the Union as the 31st state. He stayed in the vicinity long enough to cause an otherwise non-descript eminence to be forever after referred to as "Bloody Island." I had never heard of it before, but everything I've been able to turn up in the weeks since describes the "Battle of Bloody Island," or the Bloody Island/Clear Lake Massacre in horrific terms—a bad day for the Pomo however you reconcile the widely varying casualty counts. Another description, and photo of the "island" is here.

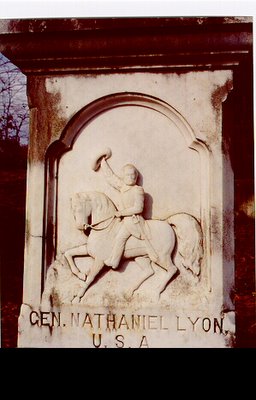

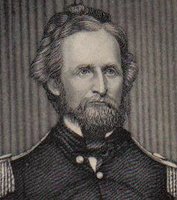

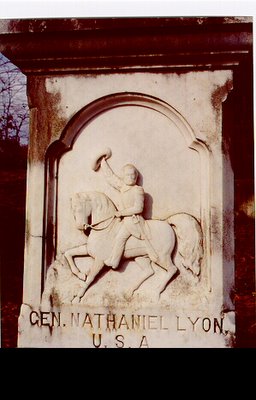

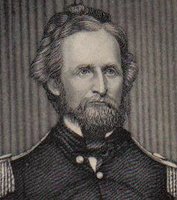

One thing's for sure, in official army parlance Nathaniel Lyon was one mean S.O.B. His righteous fervor in defense of the Union bordered on fanaticism. I have not read any biographies of the man, but his raging temper is legendary, and frequently mentioned in secondary material. Friend and foe alike knew his wrath at one time or another, from Mexico to Bleeding Kansas, and we’re left to debate whether the volatile West Pointer was the right man for the job—when the secession crisis reached full bloom—of keeping the border state of Missouri in the Union. In a place where people were choosing sides, Lyon was destined to be a hero, or a madman, depending on where one’s sympathies lay.

Portrait of General Lyon

Portrait of General Lyon

If Sherman exhibited a soldier's passion for order, Lyon embodied a passion for retribution. Undoubtedly the most quoted words from the diminutive firebrand come from the abortive peace parley of June, 1861, between Lyon—then a brigadier general in command of federal troops at the St. Louis arsenal—and pro-Confederate Missouri governor Claiborne Fox Jackson. Lyon, apparently not in the mood for compromise, abruptly and angrily ended the tête-à-tête with the declaration that "Rather than concede to the State of Missouri for one single instant the right to dictate to my Government in any manner . . . I would see you . . . and every man, woman, and child in the State, dead and buried. This means war" [quoted from McPherson's, Battle Cry of Freedom]. That’s pretty harsh, even by the standards of the day. A more talented negotiator would have stopped short of threatening genocide. Children? This comment, and Lyon’s history of unrelenting physical violence against those who would do wrong, lends credence to the dark accounts of bayoneted babies at Bloody Island.

The hot-headed Lyon did not survive the first summer of the war. Only a month after the firing on Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor, while thwarting Confederate designs in Missouri, he added another "massacre" to his future index entries (the so-called "St. Louis Massacre"). Three months after that he was killed in action on what came to be called "Bloody Hill" at the Battle of Wilson's Creek.

Photo: William Garrett Piston, coauthor of Wilson's Creek: The Second Battle of the Civil War and the Men Who Fought It, leading Civil War Forum Reunion, Wilson's Creek, March 2004.

Photo: William Garrett Piston, coauthor of Wilson's Creek: The Second Battle of the Civil War and the Men Who Fought It, leading Civil War Forum Reunion, Wilson's Creek, March 2004.

No doubt the fates decree that you can only be associated with so many "massacres," and so many landforms renamed as Bloody-something or other, before you're the one getting massacred, or whose blood is coloring the ground. Lyon was the first Union general killed during the war, and there were more than a few Confederates and Pomo Indians who thought he had it coming.

Soon after Lyon’s death, he was memorialized in 1861 when the army renamed a Colorado fort in his honor (a connection I was reminded of at the David Long site referenced earlier). It seems bitterly ironic that in 1864, Fort Lyon would serve as the staging and launch point for an expedition under Colonel John Chivington, hero of the Battle of Glorieta Pass. Chivington’s Fort Lyon volunteers gave history the Sand Creek Massacre, a misguided punitive slaughter so merciless and cruel, Lyon himself might have found it satisfactory.

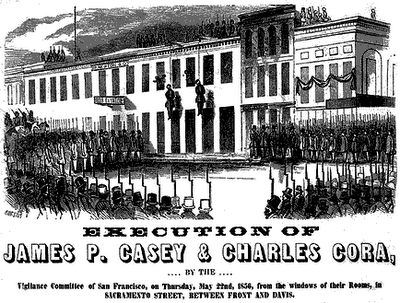

There's nothing like a gang of vigilantes, scornful of the sheriff's office and taking the law into their own hands to begin to stir "a soldier's passion for order." That quoted clause is the subtitle of Mississippi State University professor James Marszalek's 1993 biography of William T. Sherman. I thought of that book again, and Sherman, this past week when a local paper reported on the 150th anniversary of the disbanding of the 2nd Committee of Vigilance in San Francisco.

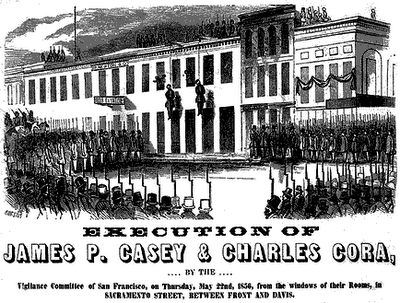

Sherman was in San Francisco during those volatile days, working at a bank. The bank is still there (see #36), on the corner of Montgomery and Jackson, in the Jackson Square area of the Financial District—one historic pocket downtown that survived the destruction of 1906. When, for reasons you can read about in the Chronicle article, the 2nd vigilante organization formed, lynched a corrupt city supervisor, James Casey, and one Charles Cora, who is reputed to have murdered a U.S. Marshall, Governor Johnson commissioned Sherman as a general officer of the militia to put down the lawless faction.

Sherman was equal to the task, and disdainful of those who would usurp legal authority (if unsympathetic to their victims). All he required, more even than volunteers—which were easily had—was arms. These were promised to him by General Wool of Mexican War fame, from the armory at Benicia (weaponry that Sherman himself had earlier accompanied around the Cape). Future Civil War admiral David Farragut at Mare Island, a naval installation that would one day serve our nations nuclear submarine fleet, promised to station a sloop off the city's shoreline as a show of strength. But Wool, for reasons we can only speculate about, not only reneged on his offer, according to Sherman he denied ever having agreed to supply the militia with rifled muskets.

It's not a scenario that would be familiar to us today: the only inventory of muskets in the state were in the Federal armory at Benecia, and the ranking U.S. army officer refused the governor's request to arm volunteer militia who had been organized to challenge a well-armed vigilante force (only 150 years later, the governor of California refused a president's request for an additional 1,500 National Guardsmen to secure the border). It was the Wild West then, and some of the spirit of the Wild West persists.

Sherman soon after resigned his militia commission, and "never afterward had any thing to do with politics in California, perfectly satisfied with that short experience." Wool, whose wartime service began in the War of 1812, retired in 1863, and died in 1869. With Wool long buried, Sherman, in his memoirs, summed up the late general's role in the abortive attempt to suppress the Committee of Vigilance: "[Governor] Johnson and Wool fought out their quarrel of veracity in the newspaper and on paper. But, in my opinion, there is not a shadow of doubt that General Wool did deliberately deceive us; that he had authority to issue arms, and that, had he adhered to his promise, we could have checked the committee before it became a fixed institution, and a part of the common law of California."

Marszalek says the episode had a strong impact on Sherman. "It was this experience with the vigilantes in California," he writes, "that helped persuade him in 1860-1861 to take a stand against Southern secessionists in order to avoid anarchy of a far greater magnitude than that which occurred in San Francisco" (108). Now I am curious to see if Michael Fellman's more recent and more personal interpretations of Sherman's character bear these things out in Citizen Sherman.

There's nothing like a gang of vigilantes, scornful of the sheriff's office and taking the law into their own hands to begin to stir "a soldier's passion for order." That quoted clause is the subtitle of Mississippi State University professor James Marszalek's 1993 biography of William T. Sherman. I thought of that book again, and Sherman, this past week when a local paper reported on the 150th anniversary of the disbanding of the 2nd Committee of Vigilance in San Francisco.

Sherman was in San Francisco during those volatile days, working at a bank. The bank is still there (see #36), on the corner of Montgomery and Jackson, in the Jackson Square area of the Financial District—one historic pocket downtown that survived the destruction of 1906. When, for reasons you can read about in the Chronicle article, the 2nd vigilante organization formed, lynched a corrupt city supervisor, James Casey, and one Charles Cora, who is reputed to have murdered a U.S. Marshall, Governor Johnson commissioned Sherman as a general officer of the militia to put down the lawless faction.

Sherman was equal to the task, and disdainful of those who would usurp legal authority (if unsympathetic to their victims). All he required, more even than volunteers—which were easily had—was arms. These were promised to him by General Wool of Mexican War fame, from the armory at Benicia (weaponry that Sherman himself had earlier accompanied around the Cape). Future Civil War admiral David Farragut at Mare Island, a naval installation that would one day serve our nations nuclear submarine fleet, promised to station a sloop off the city's shoreline as a show of strength. But Wool, for reasons we can only speculate about, not only reneged on his offer, according to Sherman he denied ever having agreed to supply the militia with rifled muskets.

It's not a scenario that would be familiar to us today: the only inventory of muskets in the state were in the Federal armory at Benecia, and the ranking U.S. army officer refused the governor's request to arm volunteer militia who had been organized to challenge a well-armed vigilante force (only 150 years later, the governor of California refused a president's request for an additional 1,500 National Guardsmen to secure the border). It was the Wild West then, and some of the spirit of the Wild West persists.

Sherman soon after resigned his militia commission, and "never afterward had any thing to do with politics in California, perfectly satisfied with that short experience." Wool, whose wartime service began in the War of 1812, retired in 1863, and died in 1869. With Wool long buried, Sherman, in his memoirs, summed up the late general's role in the abortive attempt to suppress the Committee of Vigilance: "[Governor] Johnson and Wool fought out their quarrel of veracity in the newspaper and on paper. But, in my opinion, there is not a shadow of doubt that General Wool did deliberately deceive us; that he had authority to issue arms, and that, had he adhered to his promise, we could have checked the committee before it became a fixed institution, and a part of the common law of California."

Marszalek says the episode had a strong impact on Sherman. "It was this experience with the vigilantes in California," he writes, "that helped persuade him in 1860-1861 to take a stand against Southern secessionists in order to avoid anarchy of a far greater magnitude than that which occurred in San Francisco" (108). Now I am curious to see if Michael Fellman's more recent and more personal interpretations of Sherman's character bear these things out in Citizen Sherman.

Whatever the case, Sherman certainly was fervent in his prosecution of the war to restore the Union, and law and order. When Sherman told John Bell Hood to begin evacuating civilians from Atlanta, the Confederate general replied that "the unprecedented measure you propose transcends, in studied and ingenious cruelty, all acts ever before brought to my attention in the dark history of war." That's strong stuff.

"Talk thus to the marines, but not to me," Sherman retorted, in one of the great lines in all the Official Records (look for a custom reader's guide to the Sherman-Hood Atlanta exchange later this week).

Along with the Marszalek book, the vigilante anniversary story in the Chronicle caused me to dip into Sherman's memoirs once more, one of the classics of the war that should be on everyone's Union bookshelf alongside Grant's. Sherman's recollections are not always reliable (see Albert Castel's article in Civil War History treating the Atlanta portion of Sherman's account, memorably named, "Prevaricating Through Georgia, Sherman's Memoirs as a Source on the Atlanta Campaign"), but it's a great read by a major player.

At top: Execution of Casey and Cora from The Virtual Museum of the City of San Francisco.