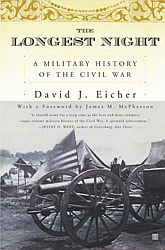

Of course, that's not to say it can't be told in a more interesting, and accurate fashion. A couple of entries ago, I mentioned that in perusing the Ayers, et. al., textbook, American Passages, I noticed that some Civil War-era, chapter ending recommendations for further reading included both James McPherson's expansive Battle Cry of Freedom, and David Eicher's strictly military narrative, The Longest Night. I see that Professor Grimsley weighed in on the subject again today as well.

I queried Professor Ayers, Dean of the College and Graduate School of Arts and Sciences at the University of Virginia, about these recommendations, and the value of military accounts. He was gracious enough to reply, and gave permission to post his comments in the blogosphere. He wrote:

To answer your question about narratives (and your eagle-eyed analysis of the bibliographical notes in Passages!): I do think there is a need for close analysis of military history AS military history. Just as we cannot understand law or literature without specialists' knowledge, so we cannot understand actions on a battlefield. I have enormous respect for those who can comprehend the complexity of armies and battles, a respect only increased by working with my colleague Gary Gallagher. That said, my own particular passion in all my work is seeing how the various parts of life connect. I approach military history from the perspective of someone who is very much a social and cultural historian but who recognizes the centrality of warfare in a war. In Presence I did my best to do justice to military events within a larger context. I'm not sure there is a new military history, but people do seem more interested in bridging, from both directions, long-standing divisions in the writing of history. And that can only be welcome.

Dr. Ayers will be our guest in The Civil War Forum on October 7th, 4:00 p.m. E.S.T., to field questions for an hour on all manner of things, from his books—including In the Presence of Mine Enemies, and What Caused the Civil War? Reflections on the South and Southern History, to his work on the fascinating digital venue, The Valley of the Shadow: Two Communities in the American Civil War.

— U. S. Grant, Memoirs

— U. S. Grant, Memoirs

For people fascinated by history—and I would hope a couple readers of this blog fit that bill—visiting the sites and scenes of historic events, the ground where historic figures trod, or any place where the connection to "What's Gone Before" is still palpable, sparks at least a low grade giddiness. You can feel it in your chest, if you're not too jaded—a sort of breathless awe—while standing in Philadelphia's Independence Hall. Or while walking amidst Anasazi ruins, or the outbuildings of Mount Vernon. Not so much at the Petrified Wood Gas Station, though that's pretty cool, too.

For those of us especially captivated by the history of the American Civil War, visiting a battlefield from that era can engender a dreamy sense of detachment from the here and now. Sometimes you have to use your imagination to try to filter out the billboards, traffic sounds, and power lines, and it's not uncommon to have to imagine an open field where 2nd- or 3rd-growth forest now covers the ground. But it's better than nothing, and some places are so pristine, and so infrequently visited that you may find you have a corner of it all to yourself. On a few occasions I've had the pleasure of being more or less alone on a battlefield, making every stop, walking through fields and woods with nothing but the sounds of my own footfalls and the wind in the trees as soundtrack to my contemplation.

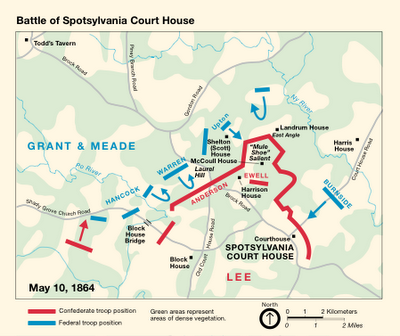

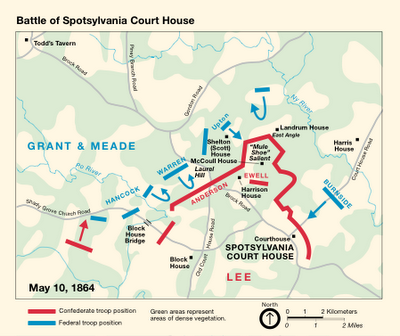

Equally moving is following in the footsteps of an ancestor, on a battlefield where they were known to be present. That's a powerful thing. The very last paper I wrote in college was on the Battle of Spotsylvania Court House, not knowing enough about the Civil War to realize I had bitten off a lengthy, busy, complicated mouthful of the Overland Campaign (lazy as I am, and knowing what I know now, I might have chosen to write on something more compact and manageable, like the Battle of Corydon.

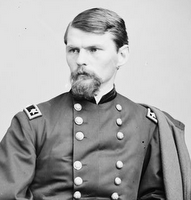

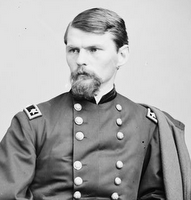

It was years later when I learned of a great-great-grandfather in the 5th Wisconsin, whose record shows him shot in the knee on May 10th, 1864. Since that was one of the 12 regiments in Emory Upton's attack on the Mule Shoe on that day, odds seem good he sustained his injury in that momentous action. I've since walked the trail through the woods that Upton's men followed as they got into position for their ultimately ill-fated assault, and strolled about the remnants of the massive works the Confederates erected there [here's a 30-second video of Robert K. Krick at the Mule Shoe with stalwart members of the Civil War Forum, on a Sunday morning in the snow, explaining why a salient in the line is not recommended—you may need to turn up the volume to catch the audio from my little camera. The small group pictured includes descendants of soldiers on both sides of the fighting on this spot]. Colonel Upton was wounded that day as well, but survived the war. The house where he shot himself nearly 17 years later, putting an end to unbearable migraines, still stands in the Presidio of San Francisco. I drive by it whenever there's time, and I wonder if the people who live there now know about the Civil War exploits of that bold and innovative officer.

Trodding today on the now-bucolic scenes of desperate carnage can be a transcendent experience. That may sound overly dramatic to those friends, neighbors, and coworkers who furrow their brows, mystified, at "vacation" photos of empty fields, ravines, and farm lanes. Nevermind them—when was the last time you saw one of them with a book in their hands, anyway?

Trodding today on the now-bucolic scenes of desperate carnage can be a transcendent experience. That may sound overly dramatic to those friends, neighbors, and coworkers who furrow their brows, mystified, at "vacation" photos of empty fields, ravines, and farm lanes. Nevermind them—when was the last time you saw one of them with a book in their hands, anyway?

Map at top from Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania National Military Park web site; photo of Emory Upton from the Library of Congress.

Many of my fellow Civil War bloggers have weighed in on the idea of a "New Military History," and the tension that some perceive exists between those who treat Civil War subjects with a strictly military narrative, and those who broaden the examination to include political and social themes. Kevin Levin weighs in at Civil War Memory with, "Why do Civil War Military Historians Hate Social History? Mark Grimsley has often commented on the institutional denigration of military history in the academy. Eric Wittenberg has made it known that nothing outside the military events of a campaign or battle hold any interest for him. My own feelings tend to align with the sentiments expressed by Sean Dail—there isn't really a discernible "New Military History." At least not one that will have the effect of supplanting the release of straight campaign and battle studies (and none of the best of these can really avoid political and social questions, since the war exists in relation to those things).

One thing about this New Military History discussion that strikes me as odd is the underlying assumption that there is an old, archaic history on the way out, while the NMH represents an evolving form naturally displacing the first. In truth, the approaches needn't be mutually exclusive, or even get in each other's way.

There is a steady, if small, market for blow-by-blow accounts of the armies in the field, and why not? Many of us find them fascinating. An annual ritual for me—with The Civil War Forum—is to read, or re-read, the best-regarded studies of a given battle in advance of a few days of tramping the battlefield with a NPS historian.

All that said, a straight military narrative can make for some dry, tedious reading, and it takes a talented author to mold it into a story worth reading. That's true of all history writing, of course, but particularly true of the kind of narratives found on the overflowing Civil War bookshelf.

I would also mention that, in my experience, strictly military accounts are more likely to be written by amateur historians than more complex efforts to place those events in a larger context (outside the vacuum). There are probably many reasons for this, and I'm not going to try to sort it out in tonight's posting. I will mention that the modern regimental history is a favorite of amateur historians, since it's too narrow for the academic, and is often inspired by a familial relationship to a member of the regiment. Most of the very best campaign and battle studies have been written by historians outside of academia—no doubt about that. Authors like Gordon Rhea, Wiley Sword, Bob Krick, Mark Bradley, and many NPS historians, have done work that may never be improved upon. I'm not sure if that's an especially Civil War-related phenomenon, but there it is.

And some of the most mediocre, or worst studies have also been written by non-academics (needless to say, obversely, a PhD degree is far from a guarantee that someone can produce a readable or worthwhile study). For one thing, it may be easier to compile the pieces of the military story when pursued as an avocation. The Official Records serve as the backbone, and from there it's a question of how authoritative one wants to make the bibliography—certain repositories, certain sources, are a must (else one risks damning reviews). The narrative is further enhanced by access to diaries and letters not commonly utilized. The savvy author, amateur or professional, will not skimp on citations, since the ranks of book reviewers may contain even more amateurs than the ranks of authors writing battle narratives. It's not uncommon to see a glowing review of a crappy book based, apparently, on nothing more than a massive bibliography and copious footnotes. The thinking is that it must be worthwhile if the author went to all that trouble.

Research is one thing, but the book still has to be written. One can string things together into a coherent, chronological report, but absent the ability to distill the research and create the story, the resulting recitation is notable less for any talent for research or writing than for the luxury of time it to assemble it all. That shortcoming is why many campaign and battle studies are treated like reference works. People use the index to zero in on a favorite regiment, or to find tidbits about certain officers, or to find an account of one part of a battle, but the balance of the book goes unread. Civil War buffs will buy a book about Stones River, for example, because their great-grandfather's regiment fought there, and whatever passing references the author devoted to that regiment are worth the price of the book. Saves the reader a trip to NARA, or to some state archives.

Getting back to the New Military History / Old Military History discussion, because I work with undergraduate college textbooks, I often peruse the history texts to see what they're saying about the Civil War. I was recently looking at the chapter-ending recommended reading section of American Passages, A History of the United States, by Ayers, Gould, Oshinsky, and Soderlund, a popular college textbook at the moment. In that section that dealt with the heart of the Civil War (in the 3rd edition), students are directed to nine books for further reading, each of which has bibliographic info and a one-line summary.

I expected to see James McPherson's classic Battle Cry of Freedom: the Civil War Era (1988) —that's as good as it gets. And naturally, there it was. But I was surprised to see the non-academic David J. Eicher's, The Longest Night: A Military History of the Civil War (2001). Readers of this blog know how highly I regard the work of David Eicher, but he's a relative newcomer on the scene, and his one-volume history of the war—while critically well received, as far as I have seen, would seem to be a redundant entry for one-book histories in a very short list of recommended texts.

Ayers, et. al. break it down this way. The editorial commentary on Eicher's book is that it "is the best one-volume military history of the war." By contrast, McPherson's Pulitzer-prize winning tome, "stands as the best one volume account of the war."

Two massive one-volume histories—one a military history, and one an account of the Civil War era—both, the best of their kind, Kevin Levin's reservations notwithstanding. I'm not sure what conclusions to draw from that, precisely (maybe an email to Ayers would prompt an illuminating reply). But one thing it says is that both approaches offer something of value to the student, and undergraduate texts are still pointing students to the "old" military history as well.

Many of my fellow Civil War bloggers have weighed in on the idea of a "New Military History," and the tension that some perceive exists between those who treat Civil War subjects with a strictly military narrative, and those who broaden the examination to include political and social themes. Kevin Levin weighs in at Civil War Memory with, "Why do Civil War Military Historians Hate Social History? Mark Grimsley has often commented on the institutional denigration of military history in the academy. Eric Wittenberg has made it known that nothing outside the military events of a campaign or battle hold any interest for him. My own feelings tend to align with the sentiments expressed by Sean Dail—there isn't really a discernible "New Military History." At least not one that will have the effect of supplanting the release of straight campaign and battle studies (and none of the best of these can really avoid political and social questions, since the war exists in relation to those things).

One thing about this New Military History discussion that strikes me as odd is the underlying assumption that there is an old, archaic history on the way out, while the NMH represents an evolving form naturally displacing the first. In truth, the approaches needn't be mutually exclusive, or even get in each other's way.

There is a steady, if small, market for blow-by-blow accounts of the armies in the field, and why not? Many of us find them fascinating. An annual ritual for me—with The Civil War Forum—is to read, or re-read, the best-regarded studies of a given battle in advance of a few days of tramping the battlefield with a NPS historian.

All that said, a straight military narrative can make for some dry, tedious reading, and it takes a talented author to mold it into a story worth reading. That's true of all history writing, of course, but particularly true of the kind of narratives found on the overflowing Civil War bookshelf.

I would also mention that, in my experience, strictly military accounts are more likely to be written by amateur historians than more complex efforts to place those events in a larger context (outside the vacuum). There are probably many reasons for this, and I'm not going to try to sort it out in tonight's posting. I will mention that the modern regimental history is a favorite of amateur historians, since it's too narrow for the academic, and is often inspired by a familial relationship to a member of the regiment. Most of the very best campaign and battle studies have been written by historians outside of academia—no doubt about that. Authors like Gordon Rhea, Wiley Sword, Bob Krick, Mark Bradley, and many NPS historians, have done work that may never be improved upon. I'm not sure if that's an especially Civil War-related phenomenon, but there it is.

And some of the most mediocre, or worst studies have also been written by non-academics (needless to say, obversely, a PhD degree is far from a guarantee that someone can produce a readable or worthwhile study). For one thing, it may be easier to compile the pieces of the military story when pursued as an avocation. The Official Records serve as the backbone, and from there it's a question of how authoritative one wants to make the bibliography—certain repositories, certain sources, are a must (else one risks damning reviews). The narrative is further enhanced by access to diaries and letters not commonly utilized. The savvy author, amateur or professional, will not skimp on citations, since the ranks of book reviewers may contain even more amateurs than the ranks of authors writing battle narratives. It's not uncommon to see a glowing review of a crappy book based, apparently, on nothing more than a massive bibliography and copious footnotes. The thinking is that it must be worthwhile if the author went to all that trouble.

Research is one thing, but the book still has to be written. One can string things together into a coherent, chronological report, but absent the ability to distill the research and create the story, the resulting recitation is notable less for any talent for research or writing than for the luxury of time it to assemble it all. That shortcoming is why many campaign and battle studies are treated like reference works. People use the index to zero in on a favorite regiment, or to find tidbits about certain officers, or to find an account of one part of a battle, but the balance of the book goes unread. Civil War buffs will buy a book about Stones River, for example, because their great-grandfather's regiment fought there, and whatever passing references the author devoted to that regiment are worth the price of the book. Saves the reader a trip to NARA, or to some state archives.

Getting back to the New Military History / Old Military History discussion, because I work with undergraduate college textbooks, I often peruse the history texts to see what they're saying about the Civil War. I was recently looking at the chapter-ending recommended reading section of American Passages, A History of the United States, by Ayers, Gould, Oshinsky, and Soderlund, a popular college textbook at the moment. In that section that dealt with the heart of the Civil War (in the 3rd edition), students are directed to nine books for further reading, each of which has bibliographic info and a one-line summary.

I expected to see James McPherson's classic Battle Cry of Freedom: the Civil War Era (1988) —that's as good as it gets. And naturally, there it was. But I was surprised to see the non-academic David J. Eicher's, The Longest Night: A Military History of the Civil War (2001). Readers of this blog know how highly I regard the work of David Eicher, but he's a relative newcomer on the scene, and his one-volume history of the war—while critically well received, as far as I have seen, would seem to be a redundant entry for one-book histories in a very short list of recommended texts.

Ayers, et. al. break it down this way. The editorial commentary on Eicher's book is that it "is the best one-volume military history of the war." By contrast, McPherson's Pulitzer-prize winning tome, "stands as the best one volume account of the war."

Two massive one-volume histories—one a military history, and one an account of the Civil War era—both, the best of their kind, Kevin Levin's reservations notwithstanding. I'm not sure what conclusions to draw from that, precisely (maybe an email to Ayers would prompt an illuminating reply). But one thing it says is that both approaches offer something of value to the student, and undergraduate texts are still pointing students to the "old" military history as well.

I watched Jeopardy the last two nights. How is it that the people who win so many thousands of dollars know everything about everything, except the things that YOU know? One of life's mysteries.

This evening, the Final Jeopardy category was U. S. History. The "answer" was something along the lines of, "He was the Union commander at Bentonville, site of the last major Confederate offensive of the Civil War." The biggest surprise was that one of the three contestants actually got it right. The reigning champ wrote, "Who was Grant?" The next contestant wrote, "Who was Lee?" [groan] Finally, the last guy went with Sherman and earned a return trip.

This had me wondering whether the program staff steers clear of topics their contestants might specialize in, or whether it's just random. Occasionally, there will be a sports-related category, and invariably, only one of the three is comfortable with it, and runs the board by naming NBA teams, or famous Hockey players. But for some reason, contestants never seem to do well with Civil War clues. Often, none of them will even hit the buzzer. And these are people who have heads full of the most arcane science facts imaginable, can identify obscure composers without pausing to think, and remember the characters in novels they read in junior high.

Granted, naming the respective commanders at Bentonville is something even a lot of Civil War buffs could not do, but you'd think everyone would know Lee fought for the South. His birthday is still a holiday in some parts of the old Confederacy, for crying out loud.

Both nights, surprisingly, the final Jeopardy category was right in my wheelhouse. Tonight, it was the aforementioned Civil War question, and last night it was a combo clue involving geography and the NFL. The clue was (paraphrasing), "Of those states that have two NFL teams, this is the only one bordering on the Mississippi River." It doesn't take a football fan long to bring up a mental map of the Mississippi River and immediately see flashing lights indicating Kansas City and St. Louis. I got that one faster than it would taken me to recall the pin number on my debit card. BUT, there was that little geographical twist -- you have to know where the Mississippi River is.

The two female contestants both guessed, "What is Minnesota." That's not unreasonable, if you're not a fan of pro football. There is a team there, on the Mississippi, and maybe they were thinking the Twin Cities each had a franchise. Then the lone male contestant's guess was revealed, on national television, taped for posterity: "What is Florida?"

Ouch! Come on, man! The Mississippi River? Florida? I can understand how people might get through all of their school years without committing to memory the names of Civil War generals, other than two or three. Or how someone could be so focused on one period of history at the expense of others. But how does someone get to adulthood without a basic grasp of—at least—the geography of their native land?

It's a personal mission of mine to ensure that my children will never be the ones who, in those horrifying surveys that make the news every so often, can't find Mexico on the map, or think Cuba is that island across the channel from Calais. I realize it's silly to project one's own interests onto the world at large, wondering why they don't share your enthusiasm for something (I don't get how someone can have no interest in history). And as long as I can remember, I have loved to scrutinize maps, globes, atlases. Really, what's better than standing before a Raven Maps masterpiece on the wall, a cocktail in one hand, a magnifying glass in the other, and an hour to kill before kickoff?

Fondly do we hope, fervently do we pray, that this mighty scourge of war may speedily pass away. Yet, if God wills that it continue until all the wealth piled by the bondsman's two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil shall be sunk, and until every drop of blood drawn with the lash shall be paid by another drawn with the sword, as was said three thousand years ago, so still it must be said "the judgments of the Lord are true and righteous altogether."

—Lincoln's Second Inaugural Address

Ten years ago, the Civil War Forum inaugurated its online, author Q&A series with an hour-long chat with James McPherson, George Henry Davis Professor of American History at Princeton University. This was not long after the publication of his book of essays, Drawn With The Sword: Reflections on the American Civil War (Oxford University Press, 1996). That’s a great book, a strong collection of finely-tuned essays that show McPherson at his reflective best. In the immaturity of youth, back when I took (more) pleasure in needling neo-Confederate types in various online venues, I adopted the title of one of McPherson’s essays, “The War of Southern Aggression,” to refer to that era. Couple that with some high praise for Sherman, and, well, my 300-baud modem could barely keep up with the digitally streaming profanity.

But back to McPherson (pronounced McFURson, if the old saying is true, “there’s no Fear in McPherson”). On May 9, 1996, while I was living in Santa Clara, California, I telephoned Dr. McPherson at a preselected time. If memory serves, he was on sabbatical at the Huntington Library in San Marino, about 400 miles south, down Pasadena way. I had him on one line, while I was logged on to the Civil War Forum with another. I relayed questions to him from members in the chat room, and typed in his responses under his name.

For me, the Q&A session after a Round Table or conference presentation is often the best part of the evening. It’s when the guest departs from prepared remarks, and really reveals their command of (hopefully), and fascination with history. These online Q&A sessions were much the same. I always started out with a few pointed questions of my own, and the rest came randomly from those in attendance. McPherson handled some fairly difficult questions with the ease and confidence of someone fluent in all aspects of the subject. I invoked the “s” word in the very first question—no sense in leaving the causes of the war till last.

Civil War Forum: While you acknowledge that the North and South had developed into distinctly different societies—with the most profound changes occurring in the North—your writings (including many essays in this book) are unequivocal on the point that slavery was the fundamental cause of the war. How do you reconcile that with a statement in "Why the Confederacy Lost" that most Confederates did not feel they were fighting for slavery, and what do you say to those who regard slavery as just one more item on a long list of issues contributing to sectional strife?

James McPherson: Slavery was not only the most important single difference between North and South, but also the basis for most of the other differences in social structure, economy, and political ideology. By 1860, each section saw the expansion of the other's social and economic institutions as a threat to the survival of its own. Technically, slavery was not the cause of the war, but of the South's secession, because the slave states saw Lincoln's election as the handwriting on the wall that doomed slavery and every thing that was associated with it in the Union. There would have been no war, however, without some such trigger as the firing on Ft. Sumter. When Confederate soldiers said they were fighting for independence and not for slavery, what they meant was that they were fighting not explicitly for slavery, but for a society of which slavery was an essential part, but one taken for granted.

Civil War Forum: Are there any credible works that, in your opinion, argue successfully that slavery was not the major cause of the war?

James McPherson: No, I don't think so. There was a school of historians known as the "Revisionists" that flourished in the 1930s and 1940s, and tried to portray inept politicians and over-stimulated public emotions as the main reason for the breakdown of compromise and the coming of the war. What that overlooks is that the issues over which politicians failed to work out a rational compromise and that stimulated public passions were all related to slavery in one way or another. The issue went too deep for compromise, and the emotions that it provoked were real and not artificial, and that is what the Revisionists failed to understand.

Civil War Forum: In your essay, "Lee Dissected," you take Alan Nolan to task somewhat for being overzealous in his critique of Lee in Lee Considered, but you conclude that Nolan probably was closer to the truth than the Marble Man mythology on the other end of the spectrum. Have any modern historians found that middle ground? Does Emory Thomas new biography break new ground in that regard?

James McPherson: Emory Thomas's biography is as close to a balanced appraisal of Lee's strengths and weaknesses as we are likely to get. But it is not accurate to say that he broke new ground so much as that he has absorbed scholarship on Lee written in recent years, including Joe Glatthaar's study of command relationships, Gary Gallagher's essays on various battles in the Eastern Theater, and Steven Woodworth's new study of the relationship between Davis and Lee. With all of these studies, we now have a solid and incisive body of writing on Lee.

Civil War Forum: In "How the Confederacy Almost Won," you state your belief that, contrary to some traditional interpretations, a Northern victory in the war was not inevitable, and was based ultimately on how the fortunes of war played out on the battlefield. You speak of some critical turning points, but do you identify any specific period or campaign as the true "high water mark" of the Confederacy?

James McPherson: There were two potential high water marks, and neither was at Gettysburg. The first came in September 1862 when two Confederate armies invaded Union territory and seemed poised for victories which, if they had occurred, would have brought European diplomatic recognition of the Confederacy and would probably have given anti-war Democrats control of the House in the fall Congressional elections. The other high water mark came nearly two years later in August 1864 when it appeared that the Northern electorate would repudiate Lincoln and his war policies in the presidential election. If that had happened the consequence might well have been Confederate independence. The traditional "high water mark" at Gettysburg overlooks the simultaneous situation at Vicksburg, whose fall probably would have canceled the benefits of a Confederate victory at Gettysburg.

Civil War Forum: In "What's the Matter With History," you allude to the distinction made by many professional historians between popular history and professional scholarship. You pointed out that although Battle Cry of Freedom won the Pulitzer, it did not garner awards from professional associations of historians. Do you think the immense popularity of Battle Cry of Freedom, which sold over 600,000 copies, is eroding the idea that professional scholarship and widely accessible history are not compatible?

James McPherson: I would hope so. That was one of my purposes in writing the book, and I think that it succeeded in bringing the findings of professional scholarship to a broader audience. At the same time, while academic historians give lip service to that purpose, the reward system within academia often is inconsistent with that lip service so that writing for a popular audience is still sometimes looked down on.

Civil War Forum: Recalling your statement, "two potential high water marks, neither at Gettysburg," J.F.C. Fuller has stated that "the Drums of Champion Hill sounded the Doom of Richmond," meaning that if Pemberton had defeated Grant there—and he had his chances—Grant would likely have been removed, and the history of the last years of the war would have been quite different.

James McPherson: Let me respond briefly. I think that is quite likely, and if Grant had not come east and become General in Chief there is a strong possibility that the Confederates could have held long enough to defeat Lincoln for reelection and thereby win the war.

Civil War Forum: Have your views on the War changed significantly over the years? And if so, what are some of those shifts?

James McPherson: When I first began studying the war, I shared the view of abolitionists and Radical Republicans that Lincoln was a conservative on the slavery issue and moved too slowly to make emancipation a war aim. But the more I study Lincoln, and the enormous pressures brought to bear on him from all sides, the more I appreciate his skillful leadership in keeping several factions working together in behalf of the principal war aim: preservation of the Union. Had he not done this so well, the North could never have won the war and slavery would obviously have survived. Therefore his leadership, focusing on the principal goal of Union, accomplished, eventually, the abolition of slavery more surely than a radical policy would have done.

Civil War Forum: As modern students, it's very easy for us to read all the debates leading up to secession. Did the average person in the South before the war have as clear a picture of the issues that were being debated?

James McPherson: No, probably not, because they lacked access to many of the Northern newspapers and other forms of expression that we can read today. But it should be remembered that Americans then were avid newspaper readers and the principal content of newspapers focused on politics. The political interest of the average citizen was much higher than it is today because it was one of the principal forms of popular entertainment, as well as of information. Thus voter participation was extremely high, and political meetings, speeches, rallies and the like attracted huge crowds and stirred up a great deal of popular interest. Therefore the level of political knowledge and commitment was high and people had a good grasp of the issues.

Civil War Forum: What is the major lesson to be learned from a study of the civil war?

James McPherson: Probably that deep-rooted and controversial social problems should be addressed before they become so huge and so divisive that they polarize the society. If some kind of gradual program to deal with economic and social problems associated with slavery had been undertaken in 1789, or even in 1820, the issue would not have become so huge and the positions so uncompromising as to cause a war. But saying that Americans should have done this is easy for us today. It may not have been possible for them to do it given the circumstances of their own time. That is why many historians have come to the conclusion that some kind of showdown between free and slave states was inevitable—so perhaps another lesson we might draw from the war is that some problems are so great that they cannot be resolved short of a social cataclysm. I don't know which is the right answer.

Civil War Forum: Before and during the war, Southerners were quite open about slavery being the issue dividing the North and South. In post-war writings, however, the issues mentioned were nebulous states' rights (rather than the specific one of slavery), tariffs, and so on. When did this change occur? And why?

James McPherson: The change occurred immediately with the end of the war. Slavery was gone, and more to the point, it was discredited. What had seemed like a proud and rational stand in favor of the institution in 1861, when Alexander Stephens called slavery "the Cornerstone of the Confederacy," now seemed in 1865 like a discredited and even an evil institution. Therefore, Southerners who were proud of their Confederate heritage sought an alternative justification and settled quickly on the issue of states rights, which was the central theme of Stephens's book, published in 1868, The War Between the States (that's where that phrase comes from—nobody to my knowledge used that phrase during the war itself).

Civil War Forum: One can reasonably argue that proponents of the Lost Cause look at the antebellum South nostalgically. Without falling into the Lost Cause mindset, do you find anything "good" or "noble" about the pre-War South?

James McPherson: Yes, I think there are many admirable things about the antebellum South: the strong sense of family; the tradition of hospitality and generosity; the ideals of noblesse oblige that stood for a sense of responsibility toward those less fortunate or weaker than one's self. The problem was that many of these admirable qualities were extended only toward those who refrained from criticizing or disagreeing with the South's social institutions and ideas.

Civil War Forum: Your response, please, to the following from Richard A. McLemore's A History of Mississippi: "The traditional view has been that Mississippi was carried out of the Union by ambitious young men who were engaged in accumulating slaves and broad acres and that the chief opposition they encountered came not from poor whites, but from wealthy planters (Whigs in many cases) who had already 'arrived' and did not wish to risk the loss of their status in a war whose outcome would be doubtful."

James McPherson: There is some truth in this argument. The wealthiest planters not only in Mississippi but in other states were in many cases Whigs and Conservatives who initially opposed secession because they feared the disruptive impact of such a radical move. Once secession became a reality, however, most of them went along with the Confederacy and some became prominent leaders in it. Nevertheless, Lincoln, among others, looked to these old Whigs when he issued a proclamation of amnesty in December 1863 inviting them to take the oath of allegiance and return to the Union. In states like Louisiana and Mississippi some of them did just that.

Civil War Forum: Do you have a favorite Civil War site you like to visit, and why?

James McPherson: My two favorite battlefields are Shiloh and Antietam. Mainly because they are today very similar in terrain and vegetation to the way they were in 1862. One can walk these battlefields and transport himself back 134 years in a way that is scarcely possible in many other battlefields where the modern world intrudes in many ways, both obvious and subtle.

Thank you everyone. Good night.