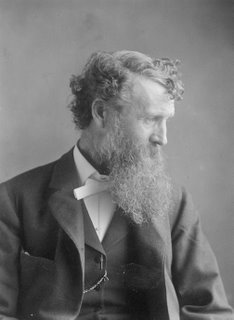

I was slow to come to appreciate the magnitude of John Muir's contribution to conservation, his role in the early establishment of the national park system, his stature as naturalist par excellence. Until I moved to San Francisco in my early 20s, Muir had not even been on my radar. Later, as I came to be captivated by the history and geography of the Sierra Nevada Mountains, Muir became such a towering figure, he was unavoidable. Reading of his adventures as a mountain man — tales of solitary sojourns in the high country expressing unabashed, poetic reverence for sacred wilderness — always makes me itch to break out the tent, gather the Coleman products, and head for the woods.

I was also slow to get around to Muir's early writings. Imagine my delight, then, when I finally came across the unpolished notes of his 1867 walk across the South, from Louisville, Kentucky to Savannah, Georgia, and on into Florida — A Thousand-Mile Walk to the Gulf (Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1916). Muir embarked on his journey to look at the plants — "grass, weeds, flowers, trees, mosses, ferns," and he comments on them passionately, and at length. But he also gives a sense of the ravaged, post-war South. Muir speaks to many freedmen along the way, enjoys the hospitality of residents in the heart of the old Confederacy, and encounters highwaymen in a largely lawless landscape where every person met on the road is a potential threat.

Happily, the entire book can be read at the Sierra Club site, here (follow links to "Books by John Muir"). I've excerpted a number of interesting passages that present observations of the Civil War South, two and a half years after the end of hostilities.

September 6. Started at the earliest bird song in hopes of seeing the great Mammoth Cave before evening. Overtook an old negro driving an ox team. Rode with him a few miles and had some interesting chat concerning war, wild fruits of the woods, et cetera. "Right heah," said he, "is where the Rebs was a-tearin' up the track, and they all a sudden thought they seed the Yankees a-comin', obah dem big hills dar, and Lo'd, how dey run." I asked him if he would like a renewal of these sad war times, when his flexible face suddenly calmed, and he said with intense earnestness, "Oh, Lo'd, want no mo wa, Lo'd no." Many of these Kentucky negroes are shrewd and intelligent, and when warmed upon a subject that interests them, are eloquent in no mean degree.

September 7. Left the hospitable Kentuckians with their sincere good wishes and bore away southward again through the deep green woods. In noble forests all day. Saw mistletoe for the first time. Part of the day I traveled with a Kentuckian from near Burkesville. He spoke to all the negroes he met with familiar kindly greetings, addressing them always as "Uncles" and "Aunts." All travelers one meets on these roads, white and black, male and female, travel on horseback. Glasgow is one of the few Southern towns that shows ordinary American life. At night with a well-to-do farmer.

As I turned to leave, after bidding her good-bye, she, evidently pitying me for my tired looks, called me back and asked me if I would like a drink of milk. This I gladly accepted, thinking that perhaps I might not be successful in getting any other nourishment for a day or two. Then I inquired whether there were any more houses on the road, nearer than North Carolina, forty or fifty miles away. "Yes," she said, "it's only two miles to the next house, but beyond that there are no houses that I know of except empty ones whose owners have been killed or driven away during the war."

Met a young African with whom I had a long talk. was amused with his eloquent narrative of coon hunting, alligators, and many superstitions. He showed me a place where a railroad train had run off the track, and assured me that the ghosts of the killed may be seen every dark night.

Had a long walk after sundown. At last was received at the house of Dr. Perkins. Saw Cape Jasmine [ Gardenia florida ] in the garden. Heard long recitals of war happenings, discussion of the slave question, and Northern politics; a thoroughly characteristic Southern family, refined in manners and kind, but immovably prejudiced on everything connected with slavery.

The family table was unlike any I ever saw before. It was circular, and the central part of it revolved. When any one wished to be helped, he placed his plate on the revolving part, which was whirled around to the host, and then whirled back with its new load. Thus every plate was revolved into place, without the assistance of any of the family.

Toward evening I arrived at the home of Mr. Cameron, a wealthy planter, who had large bands of slaves at work in his cotton fields. They still call him "Massa." He tells me that labor costs him less now than it did before the emancipation of the negroes. When I arrived I found him busily engaged in scouring the rust off some cotton-gin saws which had been lying for months at the bottom of his mill-pond to prevent Sherman's "bummers" from destroying them. The most valuable parts of the grist-mill and cotton-press were hidden in the same way. "If Bill Sherman," he said, "should come down now without his army, he would never go back."

On no subject are our ideas more warped and pitiable than on death. Instead of the sympathy, the friendly union, of life and death so apparent in Nature, we are taught that death is an accident, a deplorable punishment for the oldest sin, the arch-enemy of life, etc. Town children, especially, are steeped in this death orthodoxy, for the natural beauties of death are seldom seen or taught in towns.

Of the people of the States that I have now passed, I best like the Georgians. They have charming manners, and their dwellings are mostly larger and better than those of adjacent States. However costly or ornamental their homes or their manners, they do not, like those of the New Englander, appear as the fruits of intense and painful sacrifice and training, but are entirely divested of artificial weights and measures, and seem to pervade and twine about their characters as spontaneous growths with the durability and charm of living nature. In particular, Georgians, even the commonest, have a most charmingly cordial way of saying to strangers, as they proceed on their journey, "I wish you well, sir." The negroes of Georgia, too, are extremely mannerly and polite, and appear always to be delighted to find opportunity for obliging anybody.

The traces of war are not only apparent on the broken fields, burnt fences, mills, and woods ruthlessly slaughtered, but also on the countenances of the people. A few years after a forest has been burned another generation of bright and happy trees arises, in purest, freshest vigor; only the old trees, wholly or half dead, bear marks of the calamity. So with the people of this war-field. Happy, unscarred, and unclouded youth is growing up around the aged, half-consumed, and fallen parents, who bear in sad measure the ineffaceable marks of the farthest-reaching and most infernal of all civilized calamities.