(ten years ago, or so)

In 1995, Civil War Regiments quarterly surveyed a host of oft-published authors, historians, battlefield park rangers, and others about what they considered their “favorite” unit-related study of the Civil War era. We did not specify the size of the organization, whether a regiment, a brigade, or even an army. In fact, we did not even restrict them to unit histories, asking that they name any book that was important to them if no unit-related studies came to mind.

In the end, 35 people who have devoted a good portion of their lives to reading about the Civil War era sent in essays of varying lengths (from a few paragraphs to a couple pages). Ted Savas and I added our own, then collected them all together in the “books” issue of CWR, volume four, number three.

If you can track down a copy of issue 4:3, all of these short essays are worth reading for the authoritative commentary on what sets certain books apart from the pack, and personal thoughts on why some books had a more lasting impact than others. Even if you do have the journal copy, you may enjoy reading this recap, recalling a book or two you meant to read but forgot to find before other distractions pushed it aside. I will simply name the books and quote one or two of each respondent’s remarks while paraphrasing others.

A number of the authors chose books that cemented their interest in the subject. Others named a particular title because the featured unit was historically significant, because of the skill of the author and the narrative technique, or because the authentic observations transcended more common accounts. Some discussed the reliability of their favorite books, or availability, if rare. Several survey participants could not resist naming more than one book, and fortunately for them they were not graded on the assignment. All in all, the exercise made for a fine unit history reading list.

On the editorial side, in gathering the essays for publication, no effort was made to balance the sections to which various authors and historians might be associated (Northern or Southern historians, Eastern or Western). I don’t recall how many letters we sent out. As mentioned, about three dozen people returned an essay, two or three responded too late for publication, some unknown number did not respond at all, and one prominent historian sent an awkwardly whiny note declining to participate in the project because a recent book review we'd published -- one that took his latest work to task for a couple of items, but which nonetheless proclaimed his book to be the best on a particular campaign -- had left him “wounded.” To quote the immortal Billy Pilgrim, “so it goes.”

Civil War book buyers will recognize the names of the respondents, since most of them have a book or body of work still on the shelves, or else long-time associations with a particular battlefield park, campaign, or theater.

And so here we go, individually, our author/historian/publisher in bold, followed by his choice, and select comments. Those books that received multiple mentions are grouped together, for the most part.

William C. Davis

History of the First Kentucky Brigade, by Ed Porter Thompson, "one of the most accurate and well-founded of all unit histories by an actual participant." It was one of the earliest Confederate unit histories to appear after the war, and as Davis discovered, Thompson "was actually working on it even before the surrenders. He interviewed scores of soldiers, borrowed the few diaries in existence, and had the benefit of being custodian of a major chunk of the brigade’s official archives, which he later turned over to the National Archives.”

Steven E. Woodworth

If "unit" can refer to an army, he chooses Bruce Catton's “incomparable” Army of the Potomac trilogy: Mr. Lincoln’s Army, Glory Road, and Stillness at Appomattox. For smaller organizations, Steven named Richard Moe's, The Last Full Measure: the Life and Death of the First Minnesota Volunteers (New York, 1993), which suffered 82% casualties at Gettysburg. According to Woodworth, "Moe skillfully blends all of the aspects that went into soldiering in the Civil War, such as camp life, boredom, combat, the food, imprisonment, including such details as the soldiers' insatiable desire for news and newspapers. The narrative flows smoothly, with none of the sense of reading a meaningless compilation of facts that one gets with some books."

Gary Gallagher

Lee's Lieutenants: A Study in Command, 3 vols (New York 1942-1944), by Douglas Southall Freeman. Gallagher notes that Freeman's close identification with the Army of Northern Virginia “sometimes prompts questions about his ability to engage in detached analysis,” and also that “the aroma of the Lost Cause undoubtedly permeates Lee’s Lieutenants, and in some ways Freeman can be considered the 20th-century heir to Jubal Early in Confederate historiography.” And yet, Freeman’s masterpiece still reveals “clear-eyed criticism” of the chain of command, and “never fails to place events on the battlefield within a broader context.”

Lawrence L. Hewitt

Lee's Lieutenants. Hewitt highlights Freeman’s “fog of war” style, giving the reader “no more information than that which was available to the individual being discussed in the text.” Hewitt concludes that “as an example of unit history, Lee’s Lieutenants set a standard that can rarely be equaled.”

Theodore P. Savas

Lee's Lieutenants, the first volume of which was given to him by his Greek immigrant grandfather. At age 11, that was Ted’s first foray into Civil War literature, and it sparked a life-long passion. Ted writes that "the Introduction to the final volume is one of the most moving tributes I have ever had the pleasure of reading. . . . The colossal scope and breadth of the Civil War finally began to dawn on me after I closed the cover of the third installment."

Tom Broadfoot

Top dog at Broadfoot Publishing, Tom’s entire entry reads, “My favorite book, by far, is A Southern Woman's Story (McCowat-Mercer, Jackson, TN 1959), by Phoebe Yates Pember. If you’re going to read one book on the Civil War, that’s the one.”

John Coski

Coski named John O. Casler's, Four Years in the Stonewall Brigade, but was compelled to list three other titles as well: William Miller Owen’s, In Camp and Battle with the Washington Artillery, Ephraim A. Wilson’s, Memoirs of the War (10th Illinois Infantry), and John M. Favill’s, The Diary of a Young Officer (57th New York Infantry). Of Casler’s book, Coski wrote, “although the memoir is not a regimental history, Casler’s affiliation with the 33rd Virginia influenced me to create a character in that unit in a never-to-be-published novel about the Sharpsburg campaign." Coski, whose job I would like to have for a year or so, added, “I have had occasion to write several exhibit labels which have made John Casler and his reminiscences very real to me. In the collections of the Museum of the Confederacy are several items donated by Casler: a steel spoon and fork combination; a brooch which Casler made for his sister out of the hoof of Gen. Turner Ashby’s horse; and a small box which Casler took from the body of a dead Federal soldier at Chancellorsville. Stenciled in gothic lettering on the lid of the box is ‘Help Yourself.’”

Craig Symonds

Shelby Foote's, The Civil War, A Narrative (Random House, 1958-1974). Symonds was 12-years-old when he received the just-published Volume One. He writes, "From the first words, I was hooked." Foote's masterpiece "is not a unit history, but it shares with many of the best works of that genre the ability to focus a sharp, bright beam of light on the role of individuals--on who they were as well as on what they did." Among regimental histories, Symonds lists his favorites as John J. Pullen's, 20th Maine, a Volunteer Regiment in the Civil War, Lance J. Herdegen's and W.J.K. Beaudot's, In the Bloody Railroad Cut at Gettysburg, about the 6th Wisconsin (Dayton, 1991), and Richard Moe's, The Last Full Measure: The Life and Death of the First Minnesota Volunteers. For brigade histories, Symonds likes Alan Nolan's, The Iron Brigade (New York, 1961), and William C. Davis's, The Orphan Brigade (New York, 1980). Lastly, in the category of first-hand accounts by veterans, "my personal favorite is the irreverent account of Company Aytch, by Tennessee infantryman Sam Watkins.

Peter Cozzens

The Citizen Soldier; or Memoirs of a Volunteer (Cincinnati, 1879), by John Beatty. At age 16, Cozzens bought this book in an antiquarian bookshop for $10. A couple decades later it was worth nearly $200 and still his favorite Civil War book. Cozzens relates, "The charm of The Citizen Soldier lies in the absolute frankness -- and good humor -- with which Beatty recorded his war experiences. . . . Corps Commander Alexander McCook was a 'chucklehead,' with a grin that excited 'suspicion that he is still very green or deficient in the upper story.'" Happily, Beatty's volume has been reprinted a number of times since Cozzens first acquired a copy, making it available and affordable.

Arthur W. Bergeron, Jr.

W. H. Tunnard's, A Southern Record: the History of the Third Regiment Louisiana Infantry (Baton Rouge, 1866). Written fresh after the war, Tunnard recounts the exploits of the 3rd LA in such battles as Wilson's Creek, Elkhorn Tavern (Pea Ridge), Iuka, Corinth, Snyder's Bluff, and throughout the siege of Vicksburg (a day-by-day account) where the regiment defended the much-contested 3rd Louisiana Redan, the remnants of which you can still visit today. Bergeron concludes, "As he intended, Will Tunnard penned a story that not only commemorates the deeds of his regiment but also describes the agony and suffering its soldiers experienced during their four year service. No one interested in the Civil War will ever regret reading A Southern Record.

Leonne M. Hudson

Luis F. Emilio's A Brave Black Regiment: History of the Fifty-Fourth Regiment of Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry, 1863-1865 (Cambridge, 1868). "Judicious and analytical," Hudson writes, "A Brave Black Regiment is an impressive work not only as military history, but also because it captures the social, cultural, and political conditions of the period. . . . in a real sense, it is a study of the labyrinth of race relations in the nation during those turbulent times."

Stephen Engle

Emilio's A Brave Black Regiment, in conjunction with Russell Duncan (ed.), Blue-eyed Child of Fortune: the Civil War Letters of Colonel Robert Gould Shaw (Georgia, 1991). "Shaw's letters," Engle asserts, provide an excellent occasion to capture the essence of the Civil War, as soldiers and commanders revealed themselves by taking pen to paper as they had never done before. . . .not only was Shaw's prose among the most eloquent of any soldier writing home during the war, it was perhaps the most revealing as well." Add to that Emilio's military account: "unlike hundreds of regimental histories which are wholly inadequate in detail, Emilio's narrative of the regiment’s operations in South Carolina, Georgia and Florida (at James Island, Fort Wagner, Olustee, Honey Hill and Boykin's Mill) paints a rich description of the regiment's operations."

Noah Andre Trudeau

Emilio's A Brave Black Regiment, and, A Record of the Service of the Fifty-Fifth Regiment of Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry, a committee-written work based mostly on the diary of Colonel Charles B. Fox. “Each was authored by an officer, and each was based on extensive notes and journals of the period.” Trudeau laments that the “popular” Bantam edition of Emilio’s book “lacks the chapter Emilio added to the second edition (1894) about black prisoners of war, as well as the decision to excise the unit roster." The 55th is less known than the 54th, spending most of its service on the Charleston front. But the telling of the 55th’s story is, Trudeau says, like Emilio’s, “sober but vivid.” He supplies this example: “The men marched in silence, listening intently. It was evident to all that a battle was going on; and so deceptive was the sound, as it reverberated through the level pinelands, that it was supposed to be but a few miles off. Sore feet and weariness were forgotten.”

Chris E. Fonvielle

The Third New Hampshire and All About It (Boston, 1893), by Daniel Eldridge, who compiled “one of the most remarkable regimental histories in Civil War literature.” Fonvielle explains that this is much more than a record of the regiment’s role in battles. With chapters formed around each month and year of the unit’s service, 26 plans and maps (including 10 fold-out maps) of battlefields and campsites, 186 illustrations, 73 portraits, biographical sketches, rosters and service records (this monolithic work runs over 1,000 pages), it “is a regimental history, almanac, and compendium rolled into one."

Robert E. L. Krick

The History of a Brigade of South Carolinians, (Dayton, 1984), by J. F. J. Caldwell, on what was known first as Gregg’s, then McGowan’s Brigade. “The chief charm of Caldwell’s book – the quality that raises it above most competitors – is its wartime vintage,” Krick tells us. “It is remarkable to realize that Caldwell composed much of the text for this book while in winter quarters near Petersburg. When he came to record the brigade’s terrible moments at Fredericksburg or Spotsylvania, no doubt Caldwell called upon survivors in the trenches for whom the events still seemed fresh that winter of 1864-65.” Add to that the fact that the regiments in this brigade “featured prominently in most of the army’s big battles,” and the significance is plain. Krick recommends the 1984 Morningside reprint over the original 1866 collectible for the latter book’s enhancements: a model introduction, photos of many brigade members, and an index. Honorable mention in Krick’s essay goes to Henry W. Thomas’s History of the Doles-Cook Brigade, “both useful and attractive.”

Michael P. Musick

The History of a Brigade of South Carolinians (Philadelphia, 1866). In reading Michael Musick’s submission, I had to pause to look up the word “panegyrists,” and maybe you will, too. Musick calls Caldwell’s book “a generally credible depiction of an important fighting force within the myth-shrouded Army of Northern Virginia.” He names it his favorite for three reasons: 1) Caldwell was on hand for much of what is recorded; 2) he wrote it while events were still fresh and vivid, and “the cult of the Lost Cause had not yet descended to stifle every admission of human frailty. Our author frankly addresses the fact of desertion and the morale crisis of 1864-65.” 3) he writes well. It is, Musick concludes, “a genuine rarity, a gem to be cherished.”

Lesley J. Gordon

Warren Wilkinson’s Mother May You Never See the Sights I Have Seen: The Fifty-Seventh Massachusetts Veteran Volunteers in the Army of the Potomac 1864-1865 (Harper & Row, 1990). “Some regimental histories focus too narrowly on their subjects,” says Gordon. Not so with the late Warren Wilkinson’s history of the 57th MA, as he explores broader contexts of the soldier experience. Wilkinson “interweaves exciting scholarship from ‘new military’ historians (such as Gerald Linderman, Michael Barton, Marvin Cain, and John Keegan), into a traditional war genre to present a model for regimental histories. By the book’s end, the reader acquires not only knowledge of the regiment’s history and battle honors, but a deeper understanding of the Union war experience as a whole.”

Pat Brennan

Mother May You Never See the Sights I Have Seen: The Fifty-Seventh Massachusetts Veteran Volunteers in the Army of the Potomac 1864-1865. Brennan relates a story from the preface of Wilkinson’s book, in which the author discusses stumbling upon the story of the 57th MA while doing genealogical research – Wilkinson’s great-great-grandfather, Martin Farrell, was a corporal in the regiment – and how this interest in family history translated, “two years and 1,550 manuscript pages later,” into “one of the finest regimental histories in Civil War literature.” The regiment served for only a year and a half, but in joining the Army of the Potomac just before the launch of Grant’s 1864 Overland Campaign, it was fairly ordained the unit would not remain green for long. As Brennan points out, during the regiment’s first battle, in the Wilderness, 48% of those engaged were casualties. “Losses mounted in successive engagements – Spotsylvania, North Anna, the early battles around Petersburg, the Crater, and the bloody engagement near the Weldon Railroad. At the conclusion of the latter action, three and one-half months after the regiment crossed the Rapidan River, only 29 combat soldiers and one officer remained standing in the ranks.”

Emory Thomas

Mother May You Never See the Sights I Have Seen: The Fifty-Seventh Massachusetts Veteran Volunteers in the Army of the Potomac 1864-1865. Thomas was instrumental in getting Wilkinson’s manuscript into the hands of a publisher, and we thank him for that. He was impressed with Wilkinson’s research, and doubly so with his ability to “think and write.” Thomas asked William C. “Jack” Davis to read some of what might become the “mother” of all regimentals. Thomas writes, “Jack concurred with my opinion of Warren’s abilities and with my idea of putting Warren in touch with M. S. “Buz” Wyeth at Harper & Row (now HarperCollins). And the rest is extremely good history. Warren’s Mother has spoiled me regarding unit histories. Unless someone does what Warren does. . .with the unit rosters, I find it difficult to take his or her work seriously.”

Richard A. Sauers

History of the 51st Regiment of P.V. and V.V. (Philadelphia, 1869), by Thomas H. Parker. Sauers reports, “Parker ended the war as captain of Company I, and although his writing style sometimes degenerated into purple prose, his history of the 51st Pennsylvania is one of the finest examples of an early regimental history.” The regiment served in the IX Corps, what Parker called Burnside’s “geography class.” And indeed, they got around. Sauers concludes, “These men not only stormed the bridge at Antietam, fought in the Crater, and held the line at Knoxville, but also emptied the jail in Camden Courthouse, North Carolina, fought provost guards in Columbus, Ohio, looted a sutler near Falmouth, drank ‘rat coffee’ on shipboard, and got lost in a Virginia snowstorm.”

Part Two, forthcoming:

Submissions by Maxine Turner, Glenn LaFantasie, John F. Marszalek, Archie McDonald, Alan Nolan, William Marvel, Michael Parrish, Harry Pfanz, Brian Pohanka, James I. Robertson, Wiley Sword, Jeffry Wert, John Hubbell, Bill Miller, John Hennessy, Albert Castel, and me.

Replies to this message can be posted here.

Reflections, observations, random thoughts and bon mots, relating to the literary and geographic landscapes of American history. And book reviews too.

Thursday, December 29, 2005

Tuesday, December 27, 2005

The War, On Christmas.

Happy Holidays. And I do mean holidays. Sticking an "s" on the end of "holiday" creates a plural form of the word, and that's really handy when one is referring to multiple holidays. And while I'm at it, Season's Greetings.

For our purposes, if you want to talk about "the war on Christmas," it means you're curious about what was happening on Christmas Day during the Civil War. For queries like that, I always turn to E. B. and Barbara Long, and their endlessly helpful The Civil War Day by Day. Let's have a look-see:

For our purposes, if you want to talk about "the war on Christmas," it means you're curious about what was happening on Christmas Day during the Civil War. For queries like that, I always turn to E. B. and Barbara Long, and their endlessly helpful The Civil War Day by Day. Let's have a look-see:

December 25, 1861, Wednesday:

It was a busy Christmas Day in the White House. Mr. Lincoln and his cabinet met for lengthy discussions about the British demands for the release of Confederate commissioners Mason and Slidell. A decision was to be made the next day. The Lincolns at Christmas dinner entertained many guests.

The shooting did not stop for the holiday. The was skirmishing at Cherry, western Va., near Fort Frederick, Md.; a Union expedition operated near Danville, Mo. Off Cape Fear, N.C., a blockade-runner was taken.

December 25, 1862, Thursday:

Christmas Day brought no cessation of lesser action throughout the warring nations. Sherman's expedition operated near Milliken's Bend north of Vicksburg. Morgan's men in Kentucky fought at Green's Chapel and Bear Wallow. There was a skirmish near Warrenton, Va.; and a Federal reconnaissance from Martinsburg to Charles Town, western Va. Fighting occurred on the Wilson Creek Pike near Brentwood and at Prim's Blacksmith Shop on the Edmondson Pike, Tenn., as well as at Ripley, Miss. President and Mrs. Lincoln visited wounded soldiers in Washington hospitals.

December 25, 1863, Friday:

On the third Christmas Day of the war Federal gunboats operated in the Stono River, S.C., and Confederate field and siege guns sorely damaged U.S.S. Marblehead. There was fighting at Fort Brooke, Fla., and Federals destroyed Confederate salt works at Bear Inlet, N.C. Union cavalry under Averell reached Beverly, W. Va. In addition, Federals skirmished with Indians near Fort Gaston, Calif., and scouted from Vienna to Leesburg, Va., for three days. Shore batteries and U.S.S. Pawnee dueled at John's Island near Charleston.

December 25, 1864, a Sunday:

FEDERAL LANDINGS AT FORT FISHER FAIL

Nearly sixty warships continued the Federal bombardment of Fort Fisher, easily hitting the parapets and traverses of the sand-built fort. Meanwhile the Federal troops landed two miles north, captured a battery, and pushed close to the fort itself. However, as darkness came on, Confederate troops closed in from the north. Furthermore, assault was deemed too expensive in lives, so the troops were taken off (the last on Dec. 27), and the whole fleet returned to Hampton Roads, devoid of success but with light casualties. Fort Fisher still stood active at the entrance to the Cape Fear River. The Confederates realized this would not be the last attempt, but at the moment they had been victorious. For the Federals it was an ignominious failure, resulting in violent charges and countercharges between Butler and Porter, Butler and army officers, Butler and nearly everyone else.

Hood's Army of Tennessee reached Bainbridge on the Tennessee River. There were skirmishes at Richland Creek, and King's or Anthony's Hill or Devil's Gap, and White's Station, Tenn. Other action included an engagement at Verona, Miss., and a skirmish at Rocky Creek Church, Ga. Price's Confederate command, still retreating from Missouri, reached Laynesport, Ark.

It was a busy Christmas Day in the White House. Mr. Lincoln and his cabinet met for lengthy discussions about the British demands for the release of Confederate commissioners Mason and Slidell. A decision was to be made the next day. The Lincolns at Christmas dinner entertained many guests.

The shooting did not stop for the holiday. The was skirmishing at Cherry, western Va., near Fort Frederick, Md.; a Union expedition operated near Danville, Mo. Off Cape Fear, N.C., a blockade-runner was taken.

December 25, 1862, Thursday:

Christmas Day brought no cessation of lesser action throughout the warring nations. Sherman's expedition operated near Milliken's Bend north of Vicksburg. Morgan's men in Kentucky fought at Green's Chapel and Bear Wallow. There was a skirmish near Warrenton, Va.; and a Federal reconnaissance from Martinsburg to Charles Town, western Va. Fighting occurred on the Wilson Creek Pike near Brentwood and at Prim's Blacksmith Shop on the Edmondson Pike, Tenn., as well as at Ripley, Miss. President and Mrs. Lincoln visited wounded soldiers in Washington hospitals.

December 25, 1863, Friday:

On the third Christmas Day of the war Federal gunboats operated in the Stono River, S.C., and Confederate field and siege guns sorely damaged U.S.S. Marblehead. There was fighting at Fort Brooke, Fla., and Federals destroyed Confederate salt works at Bear Inlet, N.C. Union cavalry under Averell reached Beverly, W. Va. In addition, Federals skirmished with Indians near Fort Gaston, Calif., and scouted from Vienna to Leesburg, Va., for three days. Shore batteries and U.S.S. Pawnee dueled at John's Island near Charleston.

December 25, 1864, a Sunday:

FEDERAL LANDINGS AT FORT FISHER FAIL

Nearly sixty warships continued the Federal bombardment of Fort Fisher, easily hitting the parapets and traverses of the sand-built fort. Meanwhile the Federal troops landed two miles north, captured a battery, and pushed close to the fort itself. However, as darkness came on, Confederate troops closed in from the north. Furthermore, assault was deemed too expensive in lives, so the troops were taken off (the last on Dec. 27), and the whole fleet returned to Hampton Roads, devoid of success but with light casualties. Fort Fisher still stood active at the entrance to the Cape Fear River. The Confederates realized this would not be the last attempt, but at the moment they had been victorious. For the Federals it was an ignominious failure, resulting in violent charges and countercharges between Butler and Porter, Butler and army officers, Butler and nearly everyone else.

Hood's Army of Tennessee reached Bainbridge on the Tennessee River. There were skirmishes at Richland Creek, and King's or Anthony's Hill or Devil's Gap, and White's Station, Tenn. Other action included an engagement at Verona, Miss., and a skirmish at Rocky Creek Church, Ga. Price's Confederate command, still retreating from Missouri, reached Laynesport, Ark.

Replies to this message can be posted in The Civil War Forum here.

Monday, December 19, 2005

Favorite Historians and Guides, part one

Sunrise on Custer's Battlefield, photo by Richard Throssel (d. 1933); Created/Published 1911. Dramatic view of sunlit tombstones including a cross at Little Bighorn, Little Bighorn River, Montana. Site of the Battle of the Little Bighorn between the United States Cavalry and Native American Sioux (Lakota), Crow, Northern Cheyenne, and Arapaho and Arikara army scouts. Available at Library of Congress's American Memory web site.

With "blogger's prerogative," and the readers' indulgence, I'll begin a 2nd straight entry in the vicinity of Last Stand Hill, where troopers -- some of whom had survived many a close scrape on the battlefields of the Civil War -- found themselves without an "exit strategy" on June 25, 1876. On that day a barren, remote landscape, one that even in 2005 remains a long way from nowhere, became infused with American history for all time -- an iconic episode for which the enduring interest seems far out of proportion to the actual events that transpired there.

Some 47 years after the fight at the Little Bighorn, 33 years after Sitting Bull died -- Edwin Cole Bearss (pronounced BARs) was born in Billings. He was raised on a ranch near Hardin, Montana, mere miles from the scene of Custer's demise (there's the Civil War connection). The oft-told anecdotes relate -- and one National Park Service biography affirms -- that he named the cows on his ranch after Civil War battles and generals, the milk cow Antietam being his favorite. Ed Bearss grew up to be the closest thing we have today to a "living legend" in Civil War studies, still going strong at age 82 as the foremost tour guide and speaker on the Civil War circuit. Turns out Antietam became one of his favorite fields to visit as well.

Like a number of men in his family, including his father, and another relative, Medal of Honor winner "Hiking Hiram" Bearss, Ed joined the Marine Corps. Since he graduated high school in May of 1941, his stint in the Marines was destined to be eventful. Far from the Rosebud and Bighorn Mountains of his youth, Bearss suffered four machine gun wounds -- two more bullets than felled Custer in Montana -- on the second day of the year 1944 (which, incidentally, was New Year's Day in the U.S.). While scouting ahead of his battalion on New Britain, seven days after the landing, he moved into the field of fire of a Japanese pillbox at "Suicide Creek." Grievously wounded, Ed was confined to naval hospitals for over two years, but lived to tell the tale. For a detailed account of his encounter with the Japanese, see this interview in the June 2002 issue of Naval History magazine: "Nothing Stinks Like Blood."

In time, Ed attended Georgetown for his undergraduate degree, and completed a masters in History at Indiana. He started his storied National Park Service career at Vicksburg, the Confederacy's principal Mississippi River stronghold. Ed would spend 20 years there as historian, and regional researcher, drafting maps still much relied upon today, and penning the definitive 3-volume history of the Vicksburg Campaign, over 2,000 pages. And, in the fulfillment of every red-blooded American boy's dream, he tracked down and salvaged an ironclad warship from the bottom of a muddy river.

. . . .

In 1981 Ed became Chief Historian of the National Park Service, and held that position until his "retirement" 14 years later. Now, as Historian Emeritus with the NPS, Ed spends virtually every weekend, and then some, guiding one group or another over the historic landscapes of this country, voice booming, swagger stick tucked under his arm, eyes closed tight as he envisions the events he is narrating. The commanding Bearss delivery is one-of-a-kind, and you can get a sense of it from his many talking head roles on The History Channel, or on Ken Burns's Civil War documentary. There is also a meaty Smithsonian Associates interview that can be heard on-line here. In this interview it is revealed that the calf of the milk cow Antietam was appropriately named Sharpsburg ("McClellan's Golden Opportunity Squandered" was obviously too unwieldy).

Ed has always been willing to encourage fresh research wherever he found it, and graciously lent his considerable credibility to our publishing projects from the very start. He contributed essays and innumerable introductions for Civil War Regiments and stand-alone volumes. Later, for SW's Peninsula Campaign series, he wrote a lengthy article on Stuart's ride around McClellan, for which I drew some maps (I'll insert one of those here, once I dig out the Illustrator file and convert it to pdf). As Ed relates in the linked interview, it was a biography of Stuart -- read aloud to him by his father -- that helped spark his life-long interest in the Civil War.

Ed has always been willing to encourage fresh research wherever he found it, and graciously lent his considerable credibility to our publishing projects from the very start. He contributed essays and innumerable introductions for Civil War Regiments and stand-alone volumes. Later, for SW's Peninsula Campaign series, he wrote a lengthy article on Stuart's ride around McClellan, for which I drew some maps (I'll insert one of those here, once I dig out the Illustrator file and convert it to pdf). As Ed relates in the linked interview, it was a biography of Stuart -- read aloud to him by his father -- that helped spark his life-long interest in the Civil War.

The editorial comments Ed penned onto galleys we sent him were sometimes astonishing: corrections to errors so far removed from common knowledge and standard references we wouldn't have known where to look it up even had we recognized the miscue. Frequently he made corrections to errors introduced by the most commonly cited texts of the time, texts that authors routinely relied upon with confidence. Likewise, his corrections to map drafts made us shake our heads in wonder. Regimental fronts were realigned, troop designations were corrected or rearranged, creek beds were redirected. It's unlikely he needed to consult a book while marking up the pages.

Certainly, an encyclopedic memory is one of Ed's most fascinating attributes. In Civil War Round Table folklore, tales were told about how one could blindfold Ed, randomly transport him to part of an obscure field of battle from the Civil War, give him a moment to get his bearings, and he would then proceed to narrate the action there in dramatic and detailed fashion, with plenty of asides to spotlight one little-known figure after another. After one attends a tour with Bearss, or hears him handle a Q&A session after a talk, it is soon understood that the Bearss battlefield mystique is not exaggerated. Even more remarkable, he brings the same breadth of knowledge to virtually any other era of American military history, from the Revolution and the Indian Wars to D-Day and the South Pacific.

Ed did a live conference in The Civil War Forum nearly 10 years ago, June 20, 1996. It is interesting to learn what battlefields stand out for someone who has studied and walked them all (since this session was conducted I imagine he's visited the scene of every notable action from the war). Additionally, we asked him to name some of the officers, apart from the big names, that impressed or intrigued him most in his readings. I'll excerpt his answers here:

Certainly, an encyclopedic memory is one of Ed's most fascinating attributes. In Civil War Round Table folklore, tales were told about how one could blindfold Ed, randomly transport him to part of an obscure field of battle from the Civil War, give him a moment to get his bearings, and he would then proceed to narrate the action there in dramatic and detailed fashion, with plenty of asides to spotlight one little-known figure after another. After one attends a tour with Bearss, or hears him handle a Q&A session after a talk, it is soon understood that the Bearss battlefield mystique is not exaggerated. Even more remarkable, he brings the same breadth of knowledge to virtually any other era of American military history, from the Revolution and the Indian Wars to D-Day and the South Pacific.

Ed did a live conference in The Civil War Forum nearly 10 years ago, June 20, 1996. It is interesting to learn what battlefields stand out for someone who has studied and walked them all (since this session was conducted I imagine he's visited the scene of every notable action from the war). Additionally, we asked him to name some of the officers, apart from the big names, that impressed or intrigued him most in his readings. I'll excerpt his answers here:

Civil War Forum: You've tramped around more battlefields, more times, than just about anyone. What are a few of your favorite sites, and why? Are there any Civil War battle sites you've yet to visit?Ed Bearss: Well, I've tramped all the major battlefields. There are a few I've missed, such as Pacheco Pass out in Arizona, and the newly discovered farthest-west battle at Stanwick Station. And Missouri has over 1,000 actions, a number of them very small, with a handful of partisans or soldiers engaged, and there are a number of them I've not seen. But of the 383 identified and evaluated by the Civil War Sites Study Commission, there are probably a 1/2 a dozen that I haven't been to, and I pick up a new one every so often -- like 3 weeks ago, I visited the site of the two Cabin Creek raids out in Oklahoma, which I'd not seen before.My favorite ones. . . I'll break them into several categories: the battlefields that are maintained as parks by the Federal government, or some other public body, of these I would say in the East, Gettysburg and Antietam. If you're going to visit Gettysburg, you better be prepared to spend three days. In the West, my favorite park battlefields are Shiloh, and Perryville. Vicksburg -- I like the campaign. Most of the sites associated with the Vicksburg Campaign are outside the park. In the East, I particularly like the campaigns in the Shenandoah Valley. The country is wonderful, the road network is little changed, and there's a mix of battlefields, such as New Market, that are in quasi-public ownership -- such as with the Virginia Military Institute, and Fisher's Hill, of which 200-plus acres are owned by the Association for the Preservation of Civil War Sites [now merged with Civil War Trust]. There are a large number of others that are in various types of ownership, and I find these intriguing, and challenging to the intellect -- these battlefields that have not been developed. A wonderful site is Allatoona Pass, where I was last week, down in Georgia. I find particularly rewarding on visits to the non-big name battlefields, the great interest shown in them by the local people.. . . .Civil War Forum: In your many years studying the Civil War and the multitude of men who orchestrated the fighting, can you mention a few officers -- apart from the obvious icons like Grant and Lee -- who stand out to you as remarkable soldiers, or remarkable men.Ed Bearss: I'm going to talk about military leaders rather than political leaders. The ones that particularly interest me, beyond the icons: I'm a great admirer of Nathan Bedford Forrest. Forrest is a modern soldier, a genius who knew that war means fighting, and fighting means killing, and believed in getting the "skeer" on the enemy, and keeping him skeered. Then there is of course, [also] on the Confederate side, Patrick Cleburne, former corporal in the British Army, a dynamic leader whose advancement to possible corps command was stifled by his January, 1864 proposal to recruit African Americans into Confederate armies. A brilliant leader -- of Cleburne it was said that where his division defended, no one broke their line. And where they attacked, they only failed once -- and that was where Cleburne was killed.. . . .General Longstreet. . . of all the Confederate leaders in the war, his attacks were the most savage, and successful. Whether it is at 2nd Manassas, the 2nd Day at Gettysburg, Chickamauga, or at Wilderness on May 6th.. . . .My three favorite Union leaders that are not icons would be: Winfield Scott Hancock -- his nom de guerre, "Hancock the Superb" is earned. More than anybody else, he was responsible for turning back Lee's veterans at the Battle of Gettysburg. Phil Sheridan, like Bedford Forrest, a modern soldier. He and Forrest utilized cavalry as mounted infantry, using their mounts for mobility, and fighting afoot. They were the precursors of Erwin Rommel and George S. Patton in World War II.John Wilder. . . Wilder, a forward-looking soldier, realized the importance of the Spencer 7-shot repeating rifle. Purchasing Spencers, he sold them to his command, the Lightning Brigade, and demonstrated their deadly effectiveness first at Hoover's Gap, Tennessee, on June 24, '63, at Chickamauga.

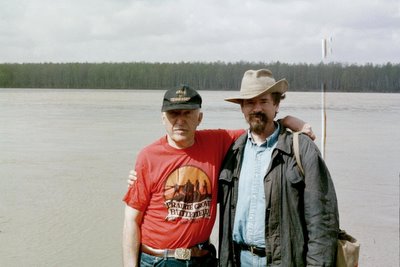

Here's a picture of Ed (left) and the late Brian Pohanka at the 4th annual Civil War Forum Battlefield Conference at Vicksburg (2000). Both Ed and Brian generously gave of their time and talents to help CWR get off the ground. Brian wrote the Union article for the 2nd issue -- an account of his beloved 5th New York and their tragic day along Young's Branch at 2nd Bull Run.

Photo by Rudy Perini. On the banks of the Mississippi River.

And returning once more to the Greasy Grass, one of the last labors of love Brian worked on before his death -- aside from his regimental history of the 5th New York, completed almost literally on his death bed -- was the "rephotography" project, Where Custer Fell. I'm going to buy myself that one for Christmas. And that brings us full circle, with the opportunity to include one more captivating Richard Throssel photo of Ed Bearss's childhood stomping grounds.

And returning once more to the Greasy Grass, one of the last labors of love Brian worked on before his death -- aside from his regimental history of the 5th New York, completed almost literally on his death bed -- was the "rephotography" project, Where Custer Fell. I'm going to buy myself that one for Christmas. And that brings us full circle, with the opportunity to include one more captivating Richard Throssel photo of Ed Bearss's childhood stomping grounds.

Sunrise on Custer Battle field, the Custer scouts are Indians who were with Custer the morning of the fight / copyright Richard Throssel. Created/Published, 1908. View at sunrise of tombstones and three mounted Native American Arapaho or Arikara scouts with rifles at the Little Bighorn Battlefield, Little Bighorn River, Montana, site of the Battle of the Little Bighorn between United States soldiers and Native American Lakota Sioux, Crow, Northern, and Cheyenne.

Sunrise on Custer Battle field, the Custer scouts are Indians who were with Custer the morning of the fight / copyright Richard Throssel. Created/Published, 1908. View at sunrise of tombstones and three mounted Native American Arapaho or Arikara scouts with rifles at the Little Bighorn Battlefield, Little Bighorn River, Montana, site of the Battle of the Little Bighorn between United States soldiers and Native American Lakota Sioux, Crow, Northern, and Cheyenne.Ed Bearss will be conducting the battlefield tours for the 11th Annual Civil War Forum Battlefield Conference in March, 2007, covering Lee's Retreat and Appomattox. Details will be published here next summer. Meanwhile, you may want to catch his next Little Bighorn tour in August, 2006.

Replies to this entry can be posted here.

Thursday, December 08, 2005

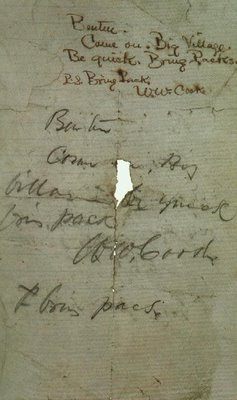

Benteen Come on. Big Village. Be quick. Bring Packs. W.W. Cooke P.S. Bring pacs

Did I mention that I need you to bring the packs? Pronto? That’s one little note I’m glad was saved. It is, of course, Custer’s last message, written by an adjutant, and carried by a bugler -- one very fortunate Italian immigrant, John Martin (born Geovanni Martini). That little piece of paper proved to be Martin’s ticket to a longer life – good for an additional 46 years. Martin spent quite a few years in the army, finally retiring as a sergeant in 1904, after which he reportedly worked as a ticket taker for the New York City subway (103rd Street Station), a long way from the Greasy Grass. See a later photo of Martin, and his tombstone, here.

Did I mention that I need you to bring the packs? Pronto? That’s one little note I’m glad was saved. It is, of course, Custer’s last message, written by an adjutant, and carried by a bugler -- one very fortunate Italian immigrant, John Martin (born Geovanni Martini). That little piece of paper proved to be Martin’s ticket to a longer life – good for an additional 46 years. Martin spent quite a few years in the army, finally retiring as a sergeant in 1904, after which he reportedly worked as a ticket taker for the New York City subway (103rd Street Station), a long way from the Greasy Grass. See a later photo of Martin, and his tombstone, here.The writing at top is apparently Benteen's rendition of what Cooke scrawled. One way or another, by way of Benteen, the note made its way to the United States Military Academy Library. I hope to see it in person one day.

Visiting the scenes of historic events is hard to beat, but history geeks love a good document. I remember when first I laid eyes on Grant's message to Simon B. Buckner, on display at the Smithsonian. There it was, in black and white. I could hardly believe my eyes -- it was just as the books had promised.

HEADQUARTERS ARMY IN THE FIELD

Camp near Fort Donelson

February 16, 1862.

General S. B. BUCKNER,

Confederate Army.

SIR: Yours of this date, proposing armistice and appointment of commissioners to settle terms of capitulation, is just received. No terms except unconditional and immediate surrender can be accepted. I propose to move immediately upon your works.

I am, sir, very respectfully, your obedient servant,

U.S. GRANT,

Brigadier-General, Commanding.

With obedient servants like that, who needs unfaithful ones?

Since that Smithsonian visit, I've enjoyed many memorable moments looking through our well-preserved documentary heritage in places like the Huntington Library, Library of Congress, and numerous regional repositories. There's something about holding the original of a hand-written, historic document that fires the imagination and gives structure and permanence to the wispy mental images one constructs while reading.

Speaking of historic documents, and speaking of the National Archives -- as I did in the last post -- all Americans need to make the trip to the NARA rotunda, once in their lives, to see the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, and the Bill of Rights. Get up close and take a look. Powerful stuff.

Of course you Civil War buffs know all about the National Archives. Almost 10 years ago (June 6, 1996), The Civil War Forum hosted an online Q&A session with Michael Musick, Subject Area Expert for Civil War Materials at the Archives. Nobody knows more about the Civil War treasures there than Mike. Here are a couple of highlights from that discussion. Of particular interest, to me, is his answer about some of the most memorable items he's encountered (pasted below). The full transcript is available in the forum (files and messages are treated the same in a search, so select "advanced search," set the range to "beginning of time" and type "Musick" in the keyword box -- that will bring up a plain text document).

from A Conversation with Michael Musick, Thursday, June 6, 1996

CWF: Mike, what one or two things that you've come across stand out most in your memory?bonus question:

MIKE MUSICK: One which occurs to me is Henry Wirz's order book from Andersonville, which is filed among the records of his trial. Another would be a moving letter from an Illinois mother, whose son was killed at Kennesaw Mountain, seeking to recover his body. There are many similar things in the files.

A third would be a letter from Lemuel T. Conner to Leonidas Polk detailing in passing the suppression of a purported slave insurrection. This has recently been published in Winthrop Jordan's Tumult and Silence at Second Creek. A fourth would be a register of wounded Union soldiers from New York who were patients at a hospital in Alexandria, Virginia. It is tucked in with 11,000 other hospital registers, and contains photographs and biographical sketches of each individual. I came across it through pure serendipity.

A fifth item would be an amnesty application from Nathan Bedford Forrest in which he offers to fight against the French in Mexico as a U. S. officer. A sixth would be my own ancestors draft enrollment record in New York City, and the report of the district provost marshall describing the tenements of German immigrants among which he lived. Another item would be the pension file for the son of Solomon Northup. Northup, Sr. was the author of the autobiography, Twelve Years a Slave, which I found a particularly moving narrative.

Another find would be the patriotic carts de visite found hidden at Mrs. Surrat's boarding house in Washington and entered in evidence at her trial. They include portraits of prominent Confederates, the state seal of Virginia, with the motto "Virginia the Mighty," and other such pro-Confederate items. Another would be the humorous photographs and drawings of military inventions submitted to the Union's chief of ordnance. Many of these have subsequently been published.

For those interested in firearms, a particularly nice discovery were some lists of serial numbers of Civil War pistols and carbines. Many of these have subsequently been published also. Another find which was enjoyable for me were some letters of Shelby Foote's ancestor, Hecekiah Foote, among the records of the Confederate Secretary of War.

CWF: Historian Bob Krick wrote in the acknowledgments to one of his books: "It is literally impossible to do adequate research for a serious Civil War book without Mike's collaboration." How, specifically, are you able to help scholars such as Krick?

MIKE MUSICK: I will interview the prospective researcher in person, or on the telephone, eliciting as best I can what that person is looking for. I try to find out where he lives, and how much time he can spend on his project. We, meaning I and my colleagues, must generally recast questions into a form that relates to our holdings. and how they are arranged and described. Often, we make people aware of other institutions and resources which will help them. You don't need to deal with me if you are doing a standard search for service and pension records.

Also, Bob Krick's kind words notwithstanding, I have a number of extremely capable colleagues who can help researchers at least as well as I. I will try to explain the Archives system to researchers, identify records which may be helpful, and explain how to go about ordering them and obtaining copies. If I know someone is interested in something, when I come across pertinent documentation, I can try to contact that person, perhaps even years afterwards. As someone who has been around a long time, with a keen interest in the War, I may well have come across something relating to the subject at hand, which has stayed in my mind. An example might be Dr. Tom Lowry and his studies of sex in the Civil War. Those kinds of documents one tends to remember.

Comments on this post may be made here.

Tuesday, December 06, 2005

"The past is never dead. It's not even past."

—From Requiem for a Nun by William Faulkner

For Confederate fortunes on August 25, 1864, there was a fleeting moment of success, and one tiny setback. On the upside, forces led by Henry Heth defeated and pushed back Union II Corps troops at Reams Station on the Weldon Railroad below Petersburg. On the not so memorable downside, J. F. Dolan was brought up on charges in California for "belching treason."

The next day, in a regular dispatch for the San Francisco Daily Morning Call, Mark Twain covered the proceedings:

One thing that strikes me about this news report is the casual way Twain dismisses the traitorous malefactor. As an author who was famously disdainful of established authority, and censorship, and as one who felt peer pressure to ever-so-briefly join the Confederate cause, I would have expected him to put in a word for free speech. I attribute it to the fact that it was wartime, and tensions were high even on the far side of the Sierra Nevada. Which leads me to some thoughts about "the fate of liberty" during wartime...

What is Past is Prologue

On the Pennsylvania Avenue side of the National Archives building in Washington D.C., rests the limestone statue entitled “The Future.” It depicts a woman looking up from a book to see what’s coming down the pike, or what lies ahead. The designer adorned the base of the monument with a quote from Shakespeare, “What is past is prologue.”

Truer words are seldom spoken, and rarely so poetically. To those of us who habitually find ourselves looking back as much as forward, mesmerized by the sheer depth and weight of all that has gone before, recent events in our own day and age naturally cause us to reflect on historic parallels. Not necessarily with a sense that history is repeating, but with the sense that some things sound awfully familiar. As in, where have we heard (read about) that before?”

Precise circumstances are very different, of course. Today's "war on terror," starting with attacks on U.S. soil and resulting in the creation of a cabinet level department to defend the homeland -- and the suggestion that the enemy is lurking, or hidden among us in sleeper cells -- has produced spirited debate about security versus civil liberties. How does a free nation prevent attacks while preserving fundamental constitutional rights?

Controversial issues surrounding the provisions of the Patriot Acts -- how far the government can or should go in curtailing civil rights in order to preserve "liberty," questions surrounding the open-ended detention of noncombatants or suspected terrorists, and the underlying implication in some quarters that dissent is the nascent expression of treason (as belched in the Twain passage above) -- all of this rings a familiar bell for those who've read much about the Civil War era. Maybe there really is nothing new under the sun. It's fascinating to look back at that earlier period of crisis, and to see how the chief executives of the warring sections responded to the constitutional balancing act within the context of their particular challenges.

There's no better place to start than with the work of Mark Neely, Jr. His book, The Fate of Liberty: Abraham Lincoln and Civil Liberties (Oxford University Press, 1991), is a trenchant exposition that all Americans would do well to read. Neely's study, which won the Pulitizer Prize for History in 1992, as well as the National Historical Society's Bell I. Wiley Book Award, details the kinds of actions that have made Lincoln, to many, an icon of constitutional abuse, especially widespread arrests, the suspension of habeas corpus, and the trial of civilians by military bodies. Though 14 years old, and dealing with the 16th president rather than the 43rd, Neely's analysis of Lincoln's wartime curtailment of civil liberties could not be timelier.

According to Neely's math (spelled out here in the Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association), 1 in 1,500 people in the North were arrested during the course of the war (though if I'm reading it right, the ratio is skewed by including the arrests of those who were citizens of seceded states, or 26.3% of the total). Neely, in this same article, goes on to say:

For eight years, neo-Confederates and other devoted Lost Cause apologists could relish Neely's book (even though, ultimately, it concludes that Lincoln's internal security network fell short of calculated constitutional abuse). Here was a Pulitzer Prize-winning work which highlighted the controversies over Lincoln's exercise of wartime powers, extra-constitutional and otherwise, with an indisputable erosion of civil liberties. To many latter day Lincoln detractors, Lincoln's actions were hard and fast validation of why the seceded states wished to distance themselves from perfidious Yankees in the first place. By contrast, Southern dedication to constitutionalism would preserve the Confederacy as an oasis for the true expression of America's founding ideals.

Then came Neely's companion treatment on the Confederacy: Southern Rights: Political Prisoners and the Myth of Confederate Constitutionalism (Virginia, 1999). Ouch. Suffice it to say, this book failed to make the bibliography of The South Was Right, by the Kennedy twins (dot.com). After the 74 citations in the "Yankee Atrocities" chapter, pp. 119-146, there may not have been much room left for Neely. One is put in mind of another Mark Twain passage, this one from Following the Equator: "the very ink with which all history is written is merely fluid prejuidice."

In the scheme of things, the States Righters may have been even more oppressive of civil liberties, to the point of regulating the movement of free citizens. Neely examines the cases of over 4,100 political prisoners in the South, the implementation of martial law in the Confederacy, and the seemingly extra-constitutional actions of the habeas corpus commissioners. His treatise on Southern rights during wartime erodes the blindly popular notion that the Confederacy, in throwing off the bonds of an overbearing central government, exemplified the spirit of personal liberty and state rights.

In reality, the dictates of war led to the same kind of centralized authority that secessionist rhetoric had railed against. Neely fairly obliterates fictions about Confederate constitutionalism. He does so with the same definitive force that Charles B. Dew's Apostles of Disunion: Southern Secession Commissioners and the Causes of the Civil War wielded, when, in one fell swoop, it became impossible for rational people to argue with a straight face that the perceived threat to slavery was not a front-and-center consideration in the secession debates.

Neely's books are the closest things we have to definitive studies on the subject of the political and practical considerations for Homeland Security in the Union and the Confederacy. Now, according to a History and Religious Studies Department web page at Penn State, Neely has finished a book called Terror and War in North America, 1864-1865. I look forward to that one.

Replies to this post can be made here, in the Civil War Forum

For Confederate fortunes on August 25, 1864, there was a fleeting moment of success, and one tiny setback. On the upside, forces led by Henry Heth defeated and pushed back Union II Corps troops at Reams Station on the Weldon Railroad below Petersburg. On the not so memorable downside, J. F. Dolan was brought up on charges in California for "belching treason."

The next day, in a regular dispatch for the San Francisco Daily Morning Call, Mark Twain covered the proceedings:

A "CONFEDERACY" CAGED

"When wine is in, wit is out." So remarked Judge Shepheard yesterday morning, when J. F. Dolan offered intoxication as an excuse for belching treason - and by the way, speaking of Judge Shepheard, it is every day becoming more and more apparent that in his incumbency, the people have got the right man in the right place. The Judge further observed that when a man is under the influence of liquor, being too bold and independent for caution, he is very likely to let out his real sentiments, and that although this Dolan pretends to be a loyal man when sober, he had no confidence in the profession of loyalty in a man who, when intoxicated, would heap curses on every thing pertaining to the Union cause, declare himself a strong Jeff. Davis man, wish for the destruction of the Union army, and that he was in the Southern army with a musket on his shoulder, as did Dolan. Mr. Riley, in whose saloon Dolan began his disloyal manifestation, and who is evidently a thorough-going Union man, created a sensation in the Court room while testifying, very decidedly in his favor, by giving forcible expression to his feelings on the subject. Dolan had gone up to his counter and called for a Jeff. Davis drink: he wanted none other than a Jeff. Davis drink. Mr. R. told him he'd be d--d if any body could get a Jeff. Davis drink in his house, and incontinently turned him out, telling him at the same time that but for the fact of his being drunk, he would give him a d--d thrashing. Dolan, notwithstanding his good loyalty when sober, was held in the sum of one thousand dollars to appear at the County Court. A little loyal when sober, and intensely disloyal when the tongue strings are loosened by liquor - and such are Copperheads.

One thing that strikes me about this news report is the casual way Twain dismisses the traitorous malefactor. As an author who was famously disdainful of established authority, and censorship, and as one who felt peer pressure to ever-so-briefly join the Confederate cause, I would have expected him to put in a word for free speech. I attribute it to the fact that it was wartime, and tensions were high even on the far side of the Sierra Nevada. Which leads me to some thoughts about "the fate of liberty" during wartime...

What is Past is Prologue

On the Pennsylvania Avenue side of the National Archives building in Washington D.C., rests the limestone statue entitled “The Future.” It depicts a woman looking up from a book to see what’s coming down the pike, or what lies ahead. The designer adorned the base of the monument with a quote from Shakespeare, “What is past is prologue.”

Truer words are seldom spoken, and rarely so poetically. To those of us who habitually find ourselves looking back as much as forward, mesmerized by the sheer depth and weight of all that has gone before, recent events in our own day and age naturally cause us to reflect on historic parallels. Not necessarily with a sense that history is repeating, but with the sense that some things sound awfully familiar. As in, where have we heard (read about) that before?”

Precise circumstances are very different, of course. Today's "war on terror," starting with attacks on U.S. soil and resulting in the creation of a cabinet level department to defend the homeland -- and the suggestion that the enemy is lurking, or hidden among us in sleeper cells -- has produced spirited debate about security versus civil liberties. How does a free nation prevent attacks while preserving fundamental constitutional rights?

Controversial issues surrounding the provisions of the Patriot Acts -- how far the government can or should go in curtailing civil rights in order to preserve "liberty," questions surrounding the open-ended detention of noncombatants or suspected terrorists, and the underlying implication in some quarters that dissent is the nascent expression of treason (as belched in the Twain passage above) -- all of this rings a familiar bell for those who've read much about the Civil War era. Maybe there really is nothing new under the sun. It's fascinating to look back at that earlier period of crisis, and to see how the chief executives of the warring sections responded to the constitutional balancing act within the context of their particular challenges.

There's no better place to start than with the work of Mark Neely, Jr. His book, The Fate of Liberty: Abraham Lincoln and Civil Liberties (Oxford University Press, 1991), is a trenchant exposition that all Americans would do well to read. Neely's study, which won the Pulitizer Prize for History in 1992, as well as the National Historical Society's Bell I. Wiley Book Award, details the kinds of actions that have made Lincoln, to many, an icon of constitutional abuse, especially widespread arrests, the suspension of habeas corpus, and the trial of civilians by military bodies. Though 14 years old, and dealing with the 16th president rather than the 43rd, Neely's analysis of Lincoln's wartime curtailment of civil liberties could not be timelier.

According to Neely's math (spelled out here in the Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association), 1 in 1,500 people in the North were arrested during the course of the war (though if I'm reading it right, the ratio is skewed by including the arrests of those who were citizens of seceded states, or 26.3% of the total). Neely, in this same article, goes on to say:

Thus the primitive state apparatus of Lincoln's day turned in a fabulously successful and efficient internal security system. Even the 2.9 percent success record beats that of the twentieth-century security apparatus of Woodrow Wilson's progressive state. Despite arrests during World War I of 6,300 enemy aliens (2,300 interned), 2,168 trials under the Espionage and Sedition Acts, and 40,000 men detained by the American Protective League's notorious "slacker raids," not one bona fide spy or saboteur was convicted by the Wilson administration. Franklin D. Roosevelt removed 120,000 Japanese-Americans from the West Coast in World War II, but there was not one single act of espionage, sabotage, or fifth-column activity by any Japanese-American on the West Coast in World War II.

For eight years, neo-Confederates and other devoted Lost Cause apologists could relish Neely's book (even though, ultimately, it concludes that Lincoln's internal security network fell short of calculated constitutional abuse). Here was a Pulitzer Prize-winning work which highlighted the controversies over Lincoln's exercise of wartime powers, extra-constitutional and otherwise, with an indisputable erosion of civil liberties. To many latter day Lincoln detractors, Lincoln's actions were hard and fast validation of why the seceded states wished to distance themselves from perfidious Yankees in the first place. By contrast, Southern dedication to constitutionalism would preserve the Confederacy as an oasis for the true expression of America's founding ideals.

Then came Neely's companion treatment on the Confederacy: Southern Rights: Political Prisoners and the Myth of Confederate Constitutionalism (Virginia, 1999). Ouch. Suffice it to say, this book failed to make the bibliography of The South Was Right, by the Kennedy twins (dot.com). After the 74 citations in the "Yankee Atrocities" chapter, pp. 119-146, there may not have been much room left for Neely. One is put in mind of another Mark Twain passage, this one from Following the Equator: "the very ink with which all history is written is merely fluid prejuidice."

In the scheme of things, the States Righters may have been even more oppressive of civil liberties, to the point of regulating the movement of free citizens. Neely examines the cases of over 4,100 political prisoners in the South, the implementation of martial law in the Confederacy, and the seemingly extra-constitutional actions of the habeas corpus commissioners. His treatise on Southern rights during wartime erodes the blindly popular notion that the Confederacy, in throwing off the bonds of an overbearing central government, exemplified the spirit of personal liberty and state rights.

In reality, the dictates of war led to the same kind of centralized authority that secessionist rhetoric had railed against. Neely fairly obliterates fictions about Confederate constitutionalism. He does so with the same definitive force that Charles B. Dew's Apostles of Disunion: Southern Secession Commissioners and the Causes of the Civil War wielded, when, in one fell swoop, it became impossible for rational people to argue with a straight face that the perceived threat to slavery was not a front-and-center consideration in the secession debates.

Neely's books are the closest things we have to definitive studies on the subject of the political and practical considerations for Homeland Security in the Union and the Confederacy. Now, according to a History and Religious Studies Department web page at Penn State, Neely has finished a book called Terror and War in North America, 1864-1865. I look forward to that one.

Replies to this post can be made here, in the Civil War Forum

Friday, December 02, 2005

W W A B D?

Precisely. I woke up this morning and asked myself the same question: “what would Ambrose Bierce do?” He’d start a Civil War blog, of course. Sure, there are already some fine blogs out there oriented toward the "late unpleasantness." Each brings a different perspective or emphasis to the online proceedings. Most internet-savvy Civil War buffs (certainly those with debilitating internet addictions) have long since discovered Dimitri Rotov’s two venues, the Civil War Book News site, and the Bookshelf blog with its penetrating insights, carefully culled news items, and curiously personal denigration of the so-called “Centennial” school of Civil War historiography. Apart from the increasingly distracting anti-McPherson fetish, when Dimitri hits his stride his blog frequently tops the charts in the Civil War arena for entertaining editorializing and meaningful musings. And boldly going where few academics dare to tread, Mark Grimsley -- he of The Hard Hand of War -- holds forth in his web log with well considered & authoritative opinions. Kevin Levin, too, supplies exceptionally thoughtful commentary with a decidedly academic slant. Other rewarding stops on the Civil War blog circuit include author Eric Wittenberg’s candid rants, Drew Wagenhoffer’s welcome focus on short-shrifted books, small presses and West/Trans-Mississippi topics (a man after my own heart), and Brett Schulte’s site. My regular circuit also takes in Mike Koepke's musings.

Still, there’s room for more. A blog is an ideal, informal medium to tout the good and trounce the bad in Civil War publishing. For my part, I’ll also be using this site as a portal to the goings-on in The Civil War Forum, one of the oldest, best informed, and most cordial on-line Civil War discussions groups around. The Forum will serve as a mirror site for many of the posts here, and that’s where you can go to post replies, should the spirit move you. You'll have to choose a screen name and password if you feel compelled to respond.

The initial OB&B entries will include lots of gratuitous background info, but this blog won't devolve into a public diary. Who really cares, after all? Let us agree to maintain the illusion that we're not all wasting time in front of our computers. I will never tell you what I had for breakfast. Unless it was really, really satisfying, in which case I'll post a recipe and you can print it out as proof to your spouse that reading this blog was time well spent. Mmmm, breakfast.

Who Died and Put Me in Charge of Praising or Disparaging the Hard Work of Earnest Authors?

Glad you asked. Someone's got to do it. I'm as qualified as the next guy (though you may want to reserve judgment), having nurtured a years-long obsession with the subject, and having edited, contributed to, and published some worthwhile Civil War books. More importantly, I've bought Civil War books (when absolutely necessary) and invested precious hours reading them. Let's be frank -- some of those authors didn't work as hard on their books as you did earning the money to buy them. And for that, they must be called out.

I will not be selling books, promoting authors, or seeking tenure with this blog. I’ll strive to avoid personal potshots in my reviews -- and in the reviews of others that I publish here -- any scorn heaped upon the work of Civil War authors will hopefully be in direct proportion to the number of hours lost pouring over their texts. Damn, I wish I could get back some of those hours.

Back when the (legendary) William Miller was editor of Civil War magazine, and hired me as book review editor, back before North and South bought out the magazine and divested itself of all animate assets on CWM's masthead, Bill had an unofficial motto for the book review section: “we kill bad books.” The proposed logo included a pirate-like reviewer replete with eye patch, and a dagger buried deep into an overpriced casebound travesty. It was about being honest with the subscribers. We were not actively on the lookout for books to trash, but the explosion of Civil War publishing in the last decade or two -- the rapid rise of self-publishing, and the appearance of innumerable small presses that directed nary a dime to editing -- fairly ensured that after the wheat was meticulously separated, the office was awash in chaff. I hasten to add that some of those small presses, like the one I started out with, arose strictly in response to that very problem, and produced several useful and lasting volumes. I'll talk about good books, too.

But Wait -- Doesn't the Name of the Blog Include "Battlefields" Too?

Good catch. You're just the kind of alert reader I was hoping to attract. Yes, OB&B is not just about books, and not just about the Civil War, for that matter. I’ll also post regular commentary on America’s battlefields -- the landscape that is the very foundation of many of the books under discussion here. Battlefield commentary will span the continent, with early posts on Appomattox, where the Civil War Forum will gather with Ed Bearss in 2007, all the way to Captain Jack’s stronghold, and the beautifully desolate spot amidst the lava flows where poor Canby met his demise.

One thing you won’t read about here is reenacting, or “living history.” With all due respect to good-intentioned hobbyists, and to top-flight historians like the greatly-missed Brian Pohanka, reenacting has always struck me as a profoundly odd pastime. I have little to say about it mainly because I do not pay attention to it. I will mention, however, that Ted Turner’s Gettysburg movie was ruined for me about three minutes in, when the scout looking for General Longstreet encountered a morbidly obese Confederate picket. How am I supposed to suspend my disbelief when the first ragtag, starving Rebel I see – a Rebel who presumably spent the previous two years relentlessly marching all over creation – reminds me less of Johnny Reb than of Jeremy Newberry, stalwart center for the San Francisco 49ers?

Gratuitous Background Department: My Life in Publishing, So Far

I worked at Stanford University Press for 9 years, from 1995-2004, one of the highlights of which was convincing SUP to publish Eicher & Eicher's Civil War High Commands, an astonishingly useful reference work that will languish in near-obscurity due to the meager marketing budgets typical of small academic presses (much as Frank Welcher’s brilliant two-volume reference on Union armies, put out by Indiana, lies largely forgotten). I'm a big fan of all of David Eicher's Civil War publications, and was honored to contribute an essay to his Gettysburg Battlefield volume. Who doesn't love a ground-breaking reference work? Well, no need to name names. You know who you are. David Eicher is a Civil War prodigy. Gettysburg battlefield tour guide? Check. Collection of all known images of R. E. Lee? Check. Biographical register of over 3,000 officers and important political figures? Check. Detailed analytical bibliography of the 1,100 most important books on the Civil War? Check. Massive single volume history of the war? Check. And all this on the side of his career as managing editor of Astronomy magazine. Some of us have trouble getting an essay written in our spare time.

Another Stanford Press highlight, for me, was working with William B. Gould IV on his great-grandfather's diary, for which I drew the maps (Diary of a Contraband: The Civil War Passage of a Black Sailor). The 1st WBG in this line, the author of the diary, was an escaped slave who joined the Union navy. His great-grandson became Chairman of the National Labor Relations Board, and a Stanford Law Professor. An American story if ever there was one.

My fascination with the literature of the Civil War reached full blossom in a years-long collaboration with Ted Savas, a fellow Iowan I met at one of Jerry Russell's conferences in San Diego sometime in the late 80s (more on Jerry Russell later). With Ted as the indefatigable catalyst, we founded the South Bay Civil War Round Table in San Jose, and breathed life into the moribund West Coast Civil War Round Table Conference by hosting a spectacular weekend event at Fisherman's Wharf in San Francisco (1990). Bob Krick flew in to be our keynote speaker in exchange for two tickets to the following Sunday's 9ers game [let me pause for a moment to clutch my chest and wince, recalling the Roger Craig fumble and Lawrence Taylor recovery that squelched SF’s last, best chance for a Super Bowl three-peat]. Arrgh.

It was at that San Francisco conference that we debuted the quarterly journal Civil War Regiments, which was our grand dream to "provide a serial outlet for the research of historians, both professional and amateur" -- an outlet for lengthy, footnoted articles that were outside the scope of the glossy periodicals, or academic journals. We rounded each issue out with lots of maps and a handful of what we insisted would be seriously useful book critiques.

CWR was a good ride. I got to meet and work with many of the best historians in the field, and some brilliant newcomers. Ted concentrated on CS manuscripts, and I took the US subjects. It strikes me as I write this that two of the contributors to that first issue passed away before their time -- Michael Mullins, who was then book review editor of Civil War News and wrote the article on the 37th Illinois, and Rich Rollins, who went on to gain some recognition for his Rank and File publications, and work on Gettysburg.

Eventually we came to feel constrained by CWR’s focus on unit histories, and so liberalized the journal’s mission to take in command issues and campaign studies in various theme issues. There will be more posts later on the experience of trying to start a quarterly journal from scratch, securing funding, establishing a subscriber base, cultivating a stable of respected contributors, all in our "spare" time, evenings and weekends, with weary wives and little babies adding to the equation. In spite of early problems with marketing and distribution, the journal filled a niche. Authors and subscribers alike were enthusiastic and supportive.

Assembling 17 issues of Civil War Regiments was an education, and I'm proud of what we produced (that marked the end of my participation — Ted put out another 8 issues, I think). It was gratifying to bring out new information on topics outside the more famous campaigns, and readers — judging by their mail — were eager to see fresh research on things like the Red River Campaign, Steele’s Camden Expedition, and the midnight battle at Wauhatchie.

Back then, there was no North & South, which now fills some of the gaps we were trying to plug (maps! footnotes! substance!). Blue & Gray magazine and Kent State's Civil War History were as good as it got, and Bob Younger's Gettysburg Magazine. Later, when (the inimitable) Bill Miller took the reins, Civil War magazine reclaimed its importance. But America's Civil War and CWTI, for the most part, ruled the roost with their mind-numbingly tedious "All Pickett's Charge, All the Time" formats.

Under the imprint of Savas Woodbury, Ted and I also began publishing collections of essays on major campaigns more deserving of attention. We started with two volumes on the Atlanta Campaign, using the best authors on the subject. At a time when some publishers were cutting back on graphics, we included fold-out maps, and pocket maps (at least with the Atlanta series). The aforementioned (über editor) Bill Miller put together three stellar volumes for us on The Peninsula Campaign of 1862. What a treasure trove. Along the way we started drafting our own maps, the better to tailor them to specific articles. For me, that led to my contributing 30 or so maps to the Library of Congress Civil War Desk Reference, a torturous project that seems better in memory.

The last book I delivered to the printer under the old Savas Woodbury imprint was Mark Bradley’s Last Stand in the Carolinas, the Battle of Bentonville. Mark was a talented writer, making the editing mercifully painless. His entire manuscript, if memory serves, was stored in an old Brother electronic typewriter, and so could not simply be submitted on a disk our computers would read. Fortunately, the Brother did have an option for transmitting via modem, so I sent Mark an old 2800 baud unit and he sent the whole book from North Carolina to California through a series of long distance phone calls. I typeset the book in the dining room of my apartment in Santa Clara, and eventually submitted the files electronically to our printer in Ann Arbor – it was our first trans-continental, all-digital book. Nowadays, of course, books, jackets, and artwork are all routinely moved via ftp, on DVD, or even as email attachments.