"The horrors of that night will never be effaced from my memory—such swearing, praying, shouting and crying I had never heard; and much of it from the same throat—imprecations followed by petitions to the Almighty, denunciations by bitter weeping.”

"The horrors of that night will never be effaced from my memory—such swearing, praying, shouting and crying I had never heard; and much of it from the same throat—imprecations followed by petitions to the Almighty, denunciations by bitter weeping.”– Chester Berry (photo at top from Harpers Weekly)

Imagine it. Upwards of 2,200 former prisoners of war, only recently released from the Confederate prison pens at Andersonville, Georgia, and Cahaba, Alabama, crowded onto a riverboat built to accommodate 300-some, steaming up the Mississippi River, headed for Cairo, Illinois, and points home. Emaciated, broken, scarred—these men were survivors. They survived camp life in Federal armies, a disease-ridden experience that killed more men in the Civil War than did bullets. They survived battle, too, before being captured. Then, they survived the obscene death rates attendant to Civil War POW camps, including Andersonville, the deadliest of all.

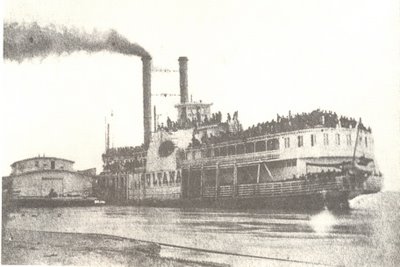

The war finally ended, and POWs North and South were released. The ragged survivors of Andersonville and Cahaba made their way by boat, on foot, and by rail, to Vicksburg, where the government promised private steamboat operators a per-person rate to transport the freed soldiers upriver to rail connections in Illinois' Little Egypt. When the Sultana got underway, every surface, every nook and cranny, was occupied by a soldier. Looking at the last known photo of the boat, taken at Helena, Arkansas on a coaling stop, the crowded conditions on the boat are clearly discernable.

(Sultana at Helena, Arkansas, loaded with former Union POWs. Library of Congress)

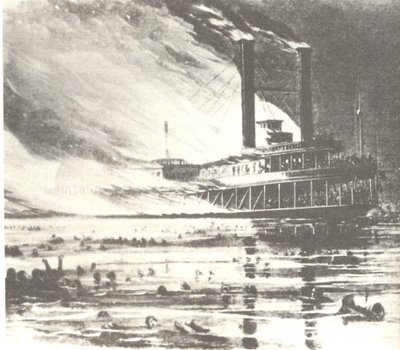

(Sultana at Helena, Arkansas, loaded with former Union POWs. Library of Congress)In the early morning hours of April 27, 1865, the Sultana's passengers were mostly asleep—at least those who could find a patch of deck, or a wall to lean against. When the recently-patched boilers exploded, many men were killed outright and dozens, or hundreds, were thrown into the water. Hundreds more quickly abandoned the boat as fire ravaged the wreckage. Untold numbers perished in the panicked mass of men clutching at anything and everything in the immediate vicinity of the burning vessel, where swimmers and non-swimmers alike struggled in keep their heads above the swift, freezing current. Even many of those who were strong, who were good swimmers, and who managed to separate from the pack, surely succumbed to the current and the elements at a time when the Mississippi was out of its banks for miles, flooding the lowlands in both directions. The lucky ones found a snag, or a half-submerged treeline, and managed to hold on till morning. Other fortunate soldiers were plucked from the river by rescue boats.

The toll was staggering. Of the roughly 2,200 men and civilians on board, only about 586 were pulled from the water alive. Of those, another 200 or so perished soon after, leaving about 300 men to tell the tale. It's hard to know why the largest, most costly maritime disaster in our nation's history remains so obscure. No doubt it's a combination of things, like the fact that it occurred on western waters, and overriding focus of the print media on other big stories, like the surrender of Confederate armies, the end of hostilities, and the assassination of President Lincoln.

Chester Berry of the 20th Michigan Infantry sought to memorialize the event, and the dead, by collecting as many firsthand accounts as possible. His book, Loss of the Sultana and Reminiscences of Survivors, was published in 1892, and included 134 testimonials (remarkably, nearly ½ of the survivors). The University of Tennessee Press just released a facsimile reprint of Berry's book, along with a meaty new introduction by David Madden. In a couple days I'll post a link here to my review of that book.

One survivor whose story does not appear in Berry's book is Romulus Tolbert, my wife's great-grandfather, whose gene pool continues to thrive in my three children. Romulus was a survivor extraordinaire. He joined the 39th Indiana infantry early in the war and saw action at Shiloh, and Stones River. In Sherman's Atlanta Campaign, on September 10th, 1864, Romulus—now veteranized with the 8th Indiana Cavalry—ran into an ambush near Campbellton, Georgia, suffering two gunshot wounds, one through the neck and jaw. He was carried to a private home in Alabama and nursed until well enough to be transferred to Cahaba prison, near Selma. People familiar with accounts of Cahaba will think of the time the Alabama River flooded, causing the prisoners to live on platforms, amidst thigh-deep water, for days. Rom was there for that, and survived it to. He had four brothers in other Indiana regiments, three of them in the famed 22nd. His oldest brother died at Perryville.

(Romulus Tolbert)

(Romulus Tolbert)No one in my wife's family knew about Romulus's Sultana adventure, or even that he had been wounded, or taken prisoner. We found that in his pension files, in the mid-80s, when I first started getting obsessive about Civil War connections. Details are scant. All that is known about his Sultana experience is that he lived, was taken to Adams hospital in Memphis, and was treated for "chills." He returned to Indiana and farmed until his death at age 77. Whether because of stoicism, or the bad memories it stirred, it wasn't a story that got handed down. We don't know if Chester Berry located Romulus and solicited his tale. Perhaps he simply declined to respond. Some that did respond had nothing more to say about that night than Abraham Cassel of the 21st Ohio, “At the time of the explosion I swam about three miles and was rescued at 10 a.m., more dead than alive.” On this day, 141 years after Romulus took to the water, and somehow managed to find dry land, I honor all those who perished, and I honor those who survived. We can take inspiration from the near-death tales of those who’ve walked away from calamity. Mostly, our problems just aren't that big.

If I start to fret too much, I'll endeavor to remember A. C. Brown's entry in Berry's book. A member of the 2nd Ohio Infantry, captured at Chickamauga, he spent time in numerous POW camps from Belle Isle to Andersonville before catching a ride on the Sultana. Stripped clean in desperate struggles with drowning men in the icy water, Brown swam for miles until catching hold of some branches above a submerged island. "I climbed a tree," he recalled, "and the water surrounding it was about ten feet deep. Now, when I hear persons talking about being hard up, I think of my condition at that time—up in a tree in the middle of the Mississippi river, a thousand miles from home, not one cent to my name, nor a pocket to put it in. . ."

2 comments:

Hey David, Great Post. I always thought it was a shame the story of Sultana never got exposure it deserves given it is the biggest maritime disaster in our history. I will have to look fo teh reprint you mentioned.

Regards

Andy

Andy,

The Chester Berry book is available directly from the University of Tennessee Press, and at Amazon (for considerably less). I'm going to be posting a review of it this weekend, making mention of other worthwhile books on the subject.

David

Post a Comment