— U. S. Grant, Memoirs

— U. S. Grant, MemoirsFor people fascinated by history—and I would hope a couple readers of this blog fit that bill—visiting the sites and scenes of historic events, the ground where historic figures trod, or any place where the connection to "What's Gone Before" is still palpable, sparks at least a low grade giddiness. You can feel it in your chest, if you're not too jaded—a sort of breathless awe—while standing in Philadelphia's Independence Hall. Or while walking amidst Anasazi ruins, or the outbuildings of Mount Vernon. Not so much at the Petrified Wood Gas Station, though that's pretty cool, too.

For those of us especially captivated by the history of the American Civil War, visiting a battlefield from that era can engender a dreamy sense of detachment from the here and now. Sometimes you have to use your imagination to try to filter out the billboards, traffic sounds, and power lines, and it's not uncommon to have to imagine an open field where 2nd- or 3rd-growth forest now covers the ground. But it's better than nothing, and some places are so pristine, and so infrequently visited that you may find you have a corner of it all to yourself. On a few occasions I've had the pleasure of being more or less alone on a battlefield, making every stop, walking through fields and woods with nothing but the sounds of my own footfalls and the wind in the trees as soundtrack to my contemplation.

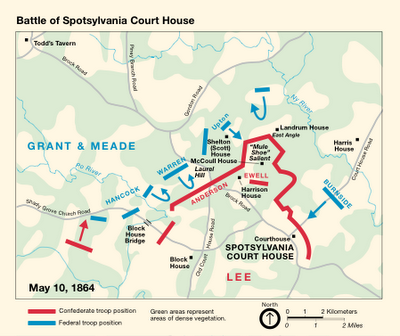

Equally moving is following in the footsteps of an ancestor, on a battlefield where they were known to be present. That's a powerful thing. The very last paper I wrote in college was on the Battle of Spotsylvania Court House, not knowing enough about the Civil War to realize I had bitten off a lengthy, busy, complicated mouthful of the Overland Campaign (lazy as I am, and knowing what I know now, I might have chosen to write on something more compact and manageable, like the Battle of Corydon.

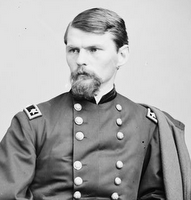

It was years later when I learned of a great-great-grandfather in the 5th Wisconsin, whose record shows him shot in the knee on May 10th, 1864. Since that was one of the 12 regiments in Emory Upton's attack on the Mule Shoe on that day, odds seem good he sustained his injury in that momentous action. I've since walked the trail through the woods that Upton's men followed as they got into position for their ultimately ill-fated assault, and strolled about the remnants of the massive works the Confederates erected there [here's a 30-second video of Robert K. Krick at the Mule Shoe with stalwart members of the Civil War Forum, on a Sunday morning in the snow, explaining why a salient in the line is not recommended—you may need to turn up the volume to catch the audio from my little camera. The small group pictured includes descendants of soldiers on both sides of the fighting on this spot]. Colonel Upton was wounded that day as well, but survived the war. The house where he shot himself nearly 17 years later, putting an end to unbearable migraines, still stands in the Presidio of San Francisco. I drive by it whenever there's time, and I wonder if the people who live there now know about the Civil War exploits of that bold and innovative officer.

Trodding today on the now-bucolic scenes of desperate carnage can be a transcendent experience. That may sound overly dramatic to those friends, neighbors, and coworkers who furrow their brows, mystified, at "vacation" photos of empty fields, ravines, and farm lanes. Nevermind them—when was the last time you saw one of them with a book in their hands, anyway?

Trodding today on the now-bucolic scenes of desperate carnage can be a transcendent experience. That may sound overly dramatic to those friends, neighbors, and coworkers who furrow their brows, mystified, at "vacation" photos of empty fields, ravines, and farm lanes. Nevermind them—when was the last time you saw one of them with a book in their hands, anyway?Map at top from Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania National Military Park web site; photo of Emory Upton from the Library of Congress.

No comments:

Post a Comment