There's nothing like a gang of vigilantes, scornful of the sheriff's office and taking the law into their own hands to begin to stir "a soldier's passion for order." That quoted clause is the subtitle of Mississippi State University professor James Marszalek's 1993 biography of William T. Sherman. I thought of that book again, and Sherman, this past week when a local paper reported on the 150th anniversary of the disbanding of the 2nd Committee of Vigilance in San Francisco.

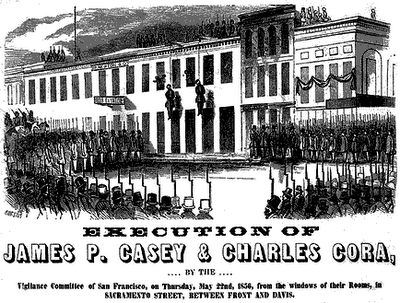

Sherman was in San Francisco during those volatile days, working at a bank. The bank is still there (see #36), on the corner of Montgomery and Jackson, in the Jackson Square area of the Financial District—one historic pocket downtown that survived the destruction of 1906. When, for reasons you can read about in the Chronicle article, the 2nd vigilante organization formed, lynched a corrupt city supervisor, James Casey, and one Charles Cora, who is reputed to have murdered a U.S. Marshall, Governor Johnson commissioned Sherman as a general officer of the militia to put down the lawless faction.

Sherman was equal to the task, and disdainful of those who would usurp legal authority (if unsympathetic to their victims). All he required, more even than volunteers—which were easily had—was arms. These were promised to him by General Wool of Mexican War fame, from the armory at Benicia (weaponry that Sherman himself had earlier accompanied around the Cape). Future Civil War admiral David Farragut at Mare Island, a naval installation that would one day serve our nations nuclear submarine fleet, promised to station a sloop off the city's shoreline as a show of strength. But Wool, for reasons we can only speculate about, not only reneged on his offer, according to Sherman he denied ever having agreed to supply the militia with rifled muskets.

It's not a scenario that would be familiar to us today: the only inventory of muskets in the state were in the Federal armory at Benecia, and the ranking U.S. army officer refused the governor's request to arm volunteer militia who had been organized to challenge a well-armed vigilante force (only 150 years later, the governor of California refused a president's request for an additional 1,500 National Guardsmen to secure the border). It was the Wild West then, and some of the spirit of the Wild West persists.

Sherman soon after resigned his militia commission, and "never afterward had any thing to do with politics in California, perfectly satisfied with that short experience." Wool, whose wartime service began in the War of 1812, retired in 1863, and died in 1869. With Wool long buried, Sherman, in his memoirs, summed up the late general's role in the abortive attempt to suppress the Committee of Vigilance: "[Governor] Johnson and Wool fought out their quarrel of veracity in the newspaper and on paper. But, in my opinion, there is not a shadow of doubt that General Wool did deliberately deceive us; that he had authority to issue arms, and that, had he adhered to his promise, we could have checked the committee before it became a fixed institution, and a part of the common law of California."

Marszalek says the episode had a strong impact on Sherman. "It was this experience with the vigilantes in California," he writes, "that helped persuade him in 1860-1861 to take a stand against Southern secessionists in order to avoid anarchy of a far greater magnitude than that which occurred in San Francisco" (108). Now I am curious to see if Michael Fellman's more recent and more personal interpretations of Sherman's character bear these things out in Citizen Sherman.

Whatever the case, Sherman certainly was fervent in his prosecution of the war to restore the Union, and law and order. When Sherman told John Bell Hood to begin evacuating civilians from Atlanta, the Confederate general replied that "the unprecedented measure you propose transcends, in studied and ingenious cruelty, all acts ever before brought to my attention in the dark history of war." That's strong stuff.

"Talk thus to the marines, but not to me," Sherman retorted, in one of the great lines in all the Official Records (look for a custom reader's guide to the Sherman-Hood Atlanta exchange later this week).

Along with the Marszalek book, the vigilante anniversary story in the Chronicle caused me to dip into Sherman's memoirs once more, one of the classics of the war that should be on everyone's Union bookshelf alongside Grant's. Sherman's recollections are not always reliable (see Albert Castel's article in Civil War History treating the Atlanta portion of Sherman's account, memorably named, "Prevaricating Through Georgia, Sherman's Memoirs as a Source on the Atlanta Campaign"), but it's a great read by a major player.

At top: Execution of Casey and Cora from The Virtual Museum of the City of San Francisco.

No comments:

Post a Comment