—tracing the Far West footprints of Civil Warriors

—tracing the Far West footprints of Civil WarriorsA couple of weeks ago we returned from another glorious camping trip in secesh country. No, not THAT secesh country, the other one, the lava-strewn State of Jefferson. Also known as the 51st state. I caught a brown trout for the first time in my life, though in truth, it more or less caught itself, as I found it on the end of the line after leaving my pole unattended for an hour or two. That counts.

My very first entry in this blog made mention of last summer's camping trip up near the Lava Beds National Monument, where one can see the site of the death of E. R. S. Canby, the first and only U.S. Army general officer killed in the nation's various Indian wars. He was murdered—shot and killed at close range during a peace conference. It never occurred to me until I was typing this, but ironically, Jefferson C. Davis —who, during the Civil War, likewise put a general in his grave—eventually took command of the troops after the demise of Canby.

Alex Trabek, take note—I have a good one for you: “Indian Wars for a $1,000: At one point in this war, opposing forces were each commanded by a leader who had personally shot and killed a general in the United States Army.” . . . “What is The Modoc War of 1873?” [a Jeff Davis aside: on one of my first visits to the Presidio Officer's Club in San Francisco, now a jewel in the National Park Service, I was studying a post-Civil War group photo of officers stationed there, and a docent or secretary pointed to one of the figures in the photo, drawing my attention to Jefferson C. Davis—one of Uncle Billy's corps commanders—whom she identified, in the proud way that curators discuss historic connections, as "the president of the Confederacy, Jefferson Davis." I had long had an interest in this Hoosier officer, as my wife had ancestors in Jefferson C. Davis's 22nd Indiana—his imposing visage is unmistakable. But I was raised too well by my mother to correct my host, who had a better story than the one I would have told. No harm, no foul.]

But enough of Jefferson Davis, and the State of Jefferson. Departing the wilds of Northern California, we split up the long drive back to the Bay Area with a stopover in Clear Lake, down in Lake County. I've mentioned before that a Civil War buff living in the Far West is forever crossing pre- and post-war paths with Civil War notables, something that helps flesh out one's perspective of those whom we too often think of only in the context of their brief Civil War careers.

Photo at right: Clear Lake from our hotel balcony.

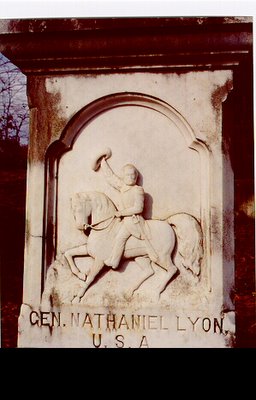

One of those well-traveled officers, Capt. Nathaniel Lyon of the 1st Dragoons, marched to the Clear Lake area in May of 1850, just months before California was admitted to the Union as the 31st state. He stayed in the vicinity long enough to cause an otherwise non-descript eminence to be forever after referred to as "Bloody Island." I had never heard of it before, but everything I've been able to turn up in the weeks since describes the "Battle of Bloody Island," or the Bloody Island/Clear Lake Massacre in horrific terms—a bad day for the Pomo however you reconcile the widely varying casualty counts. Another description, and photo of the "island" is here.

One thing's for sure, in official army parlance Nathaniel Lyon was one mean S.O.B. His righteous fervor in defense of the Union bordered on fanaticism. I have not read any biographies of the man, but his raging temper is legendary, and frequently mentioned in secondary material. Friend and foe alike knew his wrath at one time or another, from Mexico to Bleeding Kansas, and we’re left to debate whether the volatile West Pointer was the right man for the job—when the secession crisis reached full bloom—of keeping the border state of Missouri in the Union. In a place where people were choosing sides, Lyon was destined to be a hero, or a madman, depending on where one’s sympathies lay.

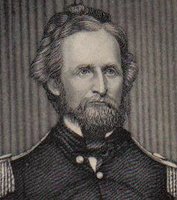

Portrait of General Lyon

Portrait of General LyonIf Sherman exhibited a soldier's passion for order, Lyon embodied a passion for retribution. Undoubtedly the most quoted words from the diminutive firebrand come from the abortive peace parley of June, 1861, between Lyon—then a brigadier general in command of federal troops at the St. Louis arsenal—and pro-Confederate Missouri governor Claiborne Fox Jackson. Lyon, apparently not in the mood for compromise, abruptly and angrily ended the tête-à-tête with the declaration that "Rather than concede to the State of Missouri for one single instant the right to dictate to my Government in any manner . . . I would see you . . . and every man, woman, and child in the State, dead and buried. This means war" [quoted from McPherson's, Battle Cry of Freedom]. That’s pretty harsh, even by the standards of the day. A more talented negotiator would have stopped short of threatening genocide. Children? This comment, and Lyon’s history of unrelenting physical violence against those who would do wrong, lends credence to the dark accounts of bayoneted babies at Bloody Island.

The hot-headed Lyon did not survive the first summer of the war. Only a month after the firing on Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor, while thwarting Confederate designs in Missouri, he added another "massacre" to his future index entries (the so-called "St. Louis Massacre"). Three months after that he was killed in action on what came to be called "Bloody Hill" at the Battle of Wilson's Creek.

The hot-headed Lyon did not survive the first summer of the war. Only a month after the firing on Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor, while thwarting Confederate designs in Missouri, he added another "massacre" to his future index entries (the so-called "St. Louis Massacre"). Three months after that he was killed in action on what came to be called "Bloody Hill" at the Battle of Wilson's Creek.

Photo: William Garrett Piston, coauthor of Wilson's Creek: The Second Battle of the Civil War and the Men Who Fought It, leading Civil War Forum Reunion, Wilson's Creek, March 2004.

Photo: William Garrett Piston, coauthor of Wilson's Creek: The Second Battle of the Civil War and the Men Who Fought It, leading Civil War Forum Reunion, Wilson's Creek, March 2004.No doubt the fates decree that you can only be associated with so many "massacres," and so many landforms renamed as Bloody-something or other, before you're the one getting massacred, or whose blood is coloring the ground. Lyon was the first Union general killed during the war, and there were more than a few Confederates and Pomo Indians who thought he had it coming.

Soon after Lyon’s death, he was memorialized in 1861 when the army renamed a Colorado fort in his honor (a connection I was reminded of at the David Long site referenced earlier). It seems bitterly ironic that in 1864, Fort Lyon would serve as the staging and launch point for an expedition under Colonel John Chivington, hero of the Battle of Glorieta Pass. Chivington’s Fort Lyon volunteers gave history the Sand Creek Massacre, a misguided punitive slaughter so merciless and cruel, Lyon himself might have found it satisfactory.

David,

ReplyDeleteYour comment about the docent's capsule view of Jefferson C Davis as President reminded me of when I visited the CW and URR Museum in Philadelphia. The friendly greeter explained some of the artifacts in a glass case.

One item came from someone who had been in a prison; I'm not aware that the museum would be showing off a miscreant, so I assumed he'd been in one of the Confederacy's prisons, and not a Union soldier being punished by superiors. If the prison name was given, that would have been the deciding factor!