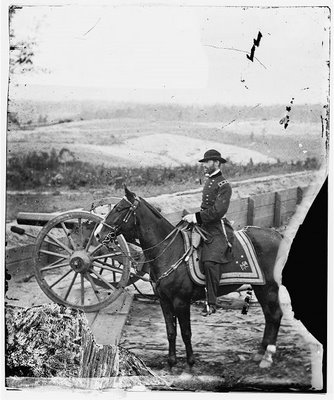

HDQRS. MILITARY DIVISION OF THE MISSISSIPPI,

Atlanta, Ga., September 20, 1864.

Maj. Gen. H. W. HALLECK, Chief of Staff, Washington, D.C.:

GENERAL: I have the honor herewith to submit copies of a correspondence between General Hood, of the Confederate army, the mayor of Atlanta, and myself touching the removal of the inhabitants of Atlanta. In explanation of the tone which marks some of these letters I will only call your attention to the fact that after I had announced my determination General Hood took upon himself to question my motive. I could not tamely submit to such impertinence, and I have seen that in violation of all official usage he has published in the Macon newspapers such parts of the correspondence as suited his purpose. This could have had no other object than to create a feeling on the part of the people, but if he expects to resort to such artifices I think I can meet him there too. It is sufficient for my Government to know that the removal of the inhabitants has been made with liberality and fairness; that it has been attended by no force, and that no women or children have suffered, unless for want of provisions by their natural protectors and friends. My real reasons for this step were, we want all the houses of Atlanta for military storage and occupation. We want to contract the lines of defenses so as to diminish the garrison to the limit necessary to defend its narrow and vital parts instead of embracing, as the lines now do, the vast suburbs. This contraction of the lines, with the necessary citadels and redoubts, will make it necessary to destroy the very houses used by families as residences. Atlanta is a fortified town, was stubbornly defended and fairly captured. As captors we have a right to it. The residence here of a poor population would compel us sooner or later to feed them or see them starve under our eyes. The residence here of the families of our enemies would be a temptation and a means to keep up a correspondence dangerous and hurtful to our cause, and a civil population calls for provost guards, and absorbs the attention of officers in listening to everlasting complaints and special grievances that are not military. These are my reasons, and if satisfactory to the Government of the United States it makes no difference whether it pleases General Hood and his people or not.

I am, with respect, your obedient servant,

W. T. SHERMAN,

Major-General, Commanding.

[Inclosure No. 1.]

HDQRS. MILITARY DIVISION OF THE MISSISSIPPI,

In the Field, Atlanta, Ga., September 7, 1864.

General HOOD, Commanding Confederate Army:

GENERAL: I have deemed it to the interest of the United States that the citizens now residing in Atlanta should remove, those who prefer it to go south and the rest north. For the latter I can provide food and transportation to points of their election in Tennessee, Kentucky, or farther north. For the former I can provide transportation by cars as far as Rough and Ready, and also wagons; but that their removal may be made with as little discomfort as possible it will be necessary for you to help the families from Rough and Ready to the cars at Lovejoy's. If you consent I will undertake to remove all families in Atlanta who prefer to go South to Rough and Ready, with all their movable effects, viz, clothing, trunks, reasonable furniture, bedding, &c., with their servants, white and black, with the proviso that no force shall be used toward the blacks one way or the other. If they want to go with their masters or mistresses they may do so, otherwise they will be sent away, unless they be men, when they may be employed by our quartermaster. Atlanta is no place for families or non-combatants, and I have no desire to send them North if you will assist in conveying them South. If this proposition meets your views I will consent to a truce in the neighborhood of Rough and Ready, stipulating that any wagons, horses, or animals, or persons sent there for the purposes herein stated shall in no manner be harmed or molested, you in your turn agreeing that any cars, wagons, carriages, persons, or animals sent to the same point shall not be interfered with. Each of us might send a guard of, say, 100 men, to maintain order and limit the truce to, say, two days after a certain time appointed. I have authorized the mayor to choose two citizens to convey to you this letter and such documents as the mayor may forward in explanation, and shall await your reply.

I have the honor to be, your obedient servant,

W. T. SHERMAN,

Major-General, Commanding.

[Inclosure No. 2.]

HDQRS. ARMY OF TENNESSEE, OFFICE CHIEF OF STAFF,

September 9, 1864.

Maj. Gen. W. T. SHERMAN.

Commanding U.S. Forces in Georgia:

GENERAL: Your letter of yesterday's date [7th] borne by James M. Ball and James R. Crew, citizens of Atlanta, is received. You say therein "I deem it to be to the interest of the United States that the citizens now residing in Atlanta should remove," &c. I do not consider that I have any alternative in this matter. I therefore accept your proposition to declare a truce of two days, or such time as may be necessary to accomplish the purpose mentioned, and shall render all assistance in my power to expedite the transportation of citizens in this direction. I suggest that a staff officer be appointed by you to superintend the removal from the city to Rough and Ready, while I appoint a like officer to control their removal farther south; that a guard of 100 men be sent by either party, as you propose, to maintain order at that place, and that the removal begin on Monday next. And now, sir, permit me to say that the unprecedented measure you propose transcends, in studied and ingenious cruelty, all acts ever before brought to my attention in the dark history of war. In the name of God and humanity I protest, believing that you will find that you are expelling from their homes and firesides the wives and children of a brave people.

I am, general, very respectfully, your obedient servant,

J. B. HOOD,

General.

[Inclosure No. 3.]

HDQRS. MILITARY DIVISION OF THE MISSISSIPPI,

In the Field, Atlanta, Ga., September 10, 1864.

General J. B. HOOD, C. S. Army, Comdg. Army of Tennessee:

GENERAL: I have the honor to acknowledge the receipt of your letter of this date [9th], at the hands of Messrs. Ball and Crew, consenting to the arrangements I had proposed to facilitate the removal south of the people of Atlanta who prefer to go in that direction. I inclose you a copy of my orders, which will, I am satisfied, accomplish my purpose perfectly. You style the measure proposed "unprecedented," and appeal to the dark history of war for a parallel as an act of "studied and ingenious cruelty." It is not unprecedented, for General Johnston himself, very wisely and properly, removed the families all the way from Dalton down, and I see no reason why Atlanta should be excepted. Nor is it necessary to appeal to the dark history of war when recent and modern examples are so handy. You, yourself, burned dwelling-houses along your parapet, and I have seen to-day fifty houses that you have rendered uninhabitable because they stood in the way of your forts and men. You defended Atlanta on a line so close to town that every cannon shot and many musket shots from our line of investment that overshot their mark went into the habitations of women and children. General Hardee did the same at Jonesborough, and General Johnston did the same last summer at Jackson, Miss. I have not accused you of heartless cruelty, but merely instance these cases of very recent occurrence, and could go on and enumerate hundreds of others and challenge any fair man to judge which of us has the heart of pity for the families of a "brave people." I say that it is kindness to these families of Atlanta to remove them now at once from scenes that women and children should not be exposed to, and the "brave people" should scorn to commit their wives and children to the rude barbarians who thus, as you say, violate the laws of war, as illustrated in the pages of its dark history. In the name of common sense I ask you not to appeal to a just God in such a sacrilegious manner; you who, in the midst of peace and prosperity, have plunged a nation into war, dark and cruel war; who dared and badgered us to battle, insulted our flag, seized our arsenals and forts that were left in the honorable custody of peaceful ordnance sergeants; seized and made "prisoners of war" the very garrisons sent to protect your people against negroes and Indians long before any overt act was committed by the, to you, hated Lincoln Government; tried to force Kentucky and Missouri into rebellion, spite of themselves; falsified the vote of Louisiana, turned loose your privateers to plunder unarmed ships; expelled Union families by the thousands; burned their houses and declared by an act of your Congress the confiscation of all debts due Northern men for goods had and received. Talk thus to the marines, but not to me, who have seen these things, and who will this day make as much sacrifice for the peace and honor of the South as the best born Southerner among you. If we must be enemies, let us be men and fight it out, as we propose to do, and not deal in such hypocritical appeals to God and humanity. God will judge us in due time, and He will pronounce whether it be more humane to fight with a town full of women, and the families of "a brave people" at our back, or to remove them in time to places of safety among their own friends and people.

W. T. SHERMAN,

Major-general, Commanding.

[Inclosure No. 4.]

ATLANTA, GA., September 11, 1864.

Maj. Gen. W. T. SHERMAN:

SIR: We, the undersigned, mayor and two of the council for the city of Atlanta, for the time being the only legal organ of the people of the said city to express their wants and wishes, ask leave most earnestly, but respectfully, to petition you to reconsider the order requiring them to leave Atlanta. At first view it struck us that the measure would involve extraordinary hardship and loss, but since we have seen the practical execution of it so far as it has progressed, and the individual condition of the people, and heard their statements as to the inconveniences, loss, and suffering attending it, we are satisfied that the amount of it will involve in the aggregate consequences appalling and heart-rending. Many poor women are in advanced state of pregnancy; others now having young children, and whose husbands, for the greater part, are either in the army, prisoners, or dead. Some say, "I have such an one sick at my house; who will wait on them when I am gone?" Others say, "what are we to do? We have no house to go to, and no means to buy, build, or rent any; no parents, relatives, or friends to go to." Another says, "I will try and take this or that article of property, but such and such things I must leave behind, though I need them much." We reply to them, "General Sherman will carry your property to Rough and Ready, and General Hood will take it thence on," and they will reply to that, "but I want to leave the railroad at such place and cannot get conveyance from there on."

We only refer to a few facts to try to illustrate in part how this measure will operate in practice. As you advanced the people north of this fell back, and before your arrival here a large portion of the people had retired south, so that the country south of this is already crowded and without houses enough to accommodate the people, and we are informed that many are now staying in churches and other outbuildings. This being so, how is it possible for the people still here (mostly women and children) to find any shelter? And how can they live through the winter in the woods? No shelter or subsistence, in the midst of strangers who know them not, and without the power to assist them much, if they were willing to do so. This is but a feeble picture of the consequences of this measure. You know the woe, the horrors and the suffering cannot be described by words; imagination can only conceive of it, and we ask you to take these things into consideration. We know your mind and time are constantly occupied with the duties of your command, which almost deters us from asking your attention to this matter, but thought it might be that you had not considered this subject in all of its awful consequences, and that on more reflection you, we hope, would not make this people an exception to all mankind, for we know of no such instance ever having occurred; surely none such in the United States, and what has this helpless people done, that they should be driven from their homes to wander strangers and outcasts and exiles, and to subsist on charity? We do not know as yet the number of people still here; of those who are here, we are satisfied a respectable number, if allowed to remain at home, could subsist for several months without assistance, and a respectable number for a much longer time, and who might not need assistance at any time. In conclusion, we most earnestly and solemnly petition you to reconsider this order, or modify it, and suffer this unfortunate people to remain at home and enjoy what little means they have.

Respectfully submitted.

JAMES M. CALHOUN,

Mayor.

E. E. RAWSON,

S.C. WELLS,

Councilmen.

[Inclosure No. 5.]

HDQRS. MILITARY DIVISION OF THE MISSISSIPPI,

In the Field, Atlanta, Ga., September 12, 1864.

JAMES M. CALHOUN, Mayor, E. E. RAWSON, and S. C. WELLS,

Representing City Council of Atlanta:

GENTLEMEN: I have your letter of the 11th, in the nature of a petition to revoke my orders removing all the inhabitants from Atlanta. I have read it carefully, and give full credit to your statements of the distress that will be occasioned by it, and yet shall not revoke my orders, simply because my orders are not designed to meet the humanities of the case, but to prepare for the future struggles in which millions of good people outside of Atlanta have a deep interest. We must have peace, not only at Atlanta but in all America. To secure this we must stop the war that now desolates our once happy and favored country. To stop war we must defeat the rebel armies that are arrayed against the laws and Constitution, which all must respect and obey. To defeat these armies we must prepare the way to reach them in their recesses provided with the arms and instruments which enable us to accomplish our purpose. Now, I know the vindictive nature of our enemy, and that we may have many years of military operations from this quarter, and therefore deem it wise and prudent to prepare in time. The use of Atlanta for warlike purposes is inconsistent with its character as a home for families. There will be no manufactures, commerce, or agriculture here for the maintenance of families, and sooner or later want will compel the inhabitants to go. Why not go now, when all the arrangements are completed for the transfer, instead of waiting till the plunging shot of contending armies will renew the scenes of the past month? Of course, I do not apprehend any such thing at this moment, but you do not suppose this army will be here until the war is over. I cannot discuss this subject with you fairly, because I cannot impart to you what I propose to do, but I assert that my military plans make it necessary for the inhabitants to go away, and I can only renew my offer of services to make their exodus in any direction as easy and comfortable as possible. You cannot qualify war in harsher terms than I will. War is cruelty and you cannot refine it, and those who brought war into our country deserve all the curses and maledictions a people can pour out. I know I had no hand in making this war, and I know I will make more sacrifices to-day than any of you to secure peace. But you cannot have peace and a division of our country. If the United States submits to a division now it will not stop, but will go on until we reap the fate of Mexico, which is eternal war. The United States does and must assert its authority wherever it once had power. If it relaxes one bit to pressure it is gone, and I know that such is the national feeling. This feeling assumes various shapes, but always comes back to that of Union. Once admit the Union, once more acknowledge the authority of the National Government, and instead of devoting your houses and streets and roads to the dread uses of war, and this army become at once your protectors and supporters, shielding you from danger, let it come from what quarter it may. I know that a few individuals cannot resist a torrent of error and passion such as swept the South into rebellion, but you can part out so that we may know those who desire a government and those who insist on war and its desolation. You might as well appeal against the thunder-storm as against these terrible hardships of war. They are inevitable, and the only way the people of Atlanta can hope once more to live in peace and quiet at home is to stop the war, which can alone be done by admitting that it began in error and is perpetuated in pride.

We don't want your negroes or your horses or your houses or your lands or anything you have, but we do want, and will have, a just obedience to the laws of the United States. That we will have, and if it involves the destruction of your improvements we cannot help it. You have heretofore read public sentiment in your newspapers that live by falsehood and excitement, and the quicker you seek for truth in other quarters the better for you. I repeat then that by the original compact of government the United States had certain rights in Georgia, which have never been relinquished and never will be; that the South began war by seizing forts, arsenals, mints, custom-houses, &c., long before Mr. Lincoln was installed and before the South had one jot or tittle of provocation. I myself have seen in Missouri, Kentucky, Tennessee, and Mississippi hundreds and thousands of women and children fleeing from your armies and desperadoes, hungry and with bleeding feet. In Memphis, Vicksburg, and Mississippi we fed thousands upon thousands of the families of rebel soldiers left on our hands and whom we could not see starve. Now that war comes home to you, you feel very different. You deprecate its horrors, but did not feel them when you sent car-loads of soldiers and ammunition and molded shells and shot to carry war into Kentucky and Tennessee, and desolate the homes of hundreds and thousands of good people who only asked to live in peace at their old homes and under the Government of their inheritance. But these comparisons are idle. I want peace, and believe it can now only be reached through union and war, and I will ever conduct war with a view to perfect an early success. But, my dear sirs, when that peace does come, you may call on me for anything. Then will I share with you the last cracker, and watch with you to shield your homes and families against danger from every quarter. Now you must go, and take with you the old and feeble, feed and nurse them and build for them in more quiet places proper habitations to shield them against the weather until the mad passions of men cool down and allow the Union and peace once more to settle over your old homes at Atlanta.

Yours, in haste,

W. T. SHERMAN,

Major-General, Commanding.

[Inclosure No. 6.]

HEADQUARTERS ARMY OF TENNESSEE,

September 12, 1864.

Maj. Gen. W. T. SHERMAN,

Commanding Military Division of the Mississippi:

GENERAL; I have the honor to acknowledge the receipt of your letter of the 9th [10th] instant, with its inclosure, in reference to the women, children, and others whom you have thought proper to expel from their homes in the city of Atlanta. Had you seen proper to let the matter rest there, I would gladly have allowed your letter to close this correspondence, and without your expressing it in words would have been willing to believe that whilst "the interests of the United States," in your opinion, compelled you to an act of barbarous cruelty, you regretted the necessity, and we would have dropped the subject. But you have chosen to indulge in statements which I feel compelled to notice, at least so far as to signify my dissent and not allow silence in regard to them to be construed as acquiescence. I see nothing in your communication which induces me to modify the language of condemnation with which I characterized your order. It but strengthens me in the opinion that it stands" pre-eminent in the dark history of war, for studied and ingenious cruelty." Your original order was stripped of all pretenses; you announced the edict for the sole reason that it was "to the interest of the United States." This alone you offered to us and the civilized world as an all-sufficient reason for disregarding the laws of God and man. You say that "General Johnston himself, very wisely and properly, removed the families all the way from Dalton down," It is due to that gallant soldier and gentleman to say that no act of his distinguished career gives the least color to your unfounded aspersions upon his conduct. He depopulated no villages nor towns nor cities, either friendly or hostile. He offered and extended friendly aid to his unfortunate fellow-citizens who desired to flee from your fraternal embraces. You are equally unfortunate in your attempt to find a justification for this act of cruelty either in the defense of Jonesborough, by General Hardee, or of Atlanta by myself. General Hardee defended his position in front of Jonesborough at the expense of injury to the houses, an ordinary, proper, and justifiable act of war. I defended Atlanta at the same risk and cost. If there was any fault in either case, it was your own, in not giving notice, especially in the case of Atlanta, of your purpose to shell the town, which is usual in war among civilized nations. No inhabitant was expelled from his home and fireside by the orders of General Hardee or myself, and therefore your recent order can find no support from the conduct of either of us. I feel no other emotion than pain in reading that portion of your letter which attempts to justify your shelling Atlanta without notice under pretense that I defended Atlanta upon a line so close to town that every cannon shot, and many musket balls from your line of investment, that over-shot their mark went into the habitations of women and children. I made no complaint of your firing into Atlanta in any way you thought proper. I make none now, but there are a hundred thousand witnesses that you fired into the habitations of women and children for weeks, firing far above and miles beyond my line of defense. I have too good an opinion, founded both upon observation and experience, of the skill of your artillerists to credit the insinuation that they for several weeks unintentionally fired too high for my modest field-works, and slaughtered women and children by accident and want of skill.

The residue of your letter is rather discussion. It opens a wide field for the discussion of questions which I do not feel are committed to me. I am only a general of one of the armies of the Confederate States, charged with military operations in the field, under the direction of my superior officers, and I am not called upon to discuss with you the causes of the present war, or the political questions which led to or resulted from it. These grave and important questions have been committed to far abler hands than mine, and I shall only refer to them so far as to repel any unjust conclusion which might be drawn from my silence. You charge my country with "daring and badgering you to battle." The truth is, we sent commissioners to you respectfully offering a peaceful separation before the first gun was fired on either side. You say we insulted your flag. The truth is we fired upon it and those who fought under it when you came to our doors upon the mission of subjugation. You say we seized upon your forts and arsenals and made prisoners of the garrisons sent to protect us against negroes and Indians. The truth is, we, by force of arms, drove out insolent intruders, and took possession of our own forts and arsenals to resist your claims to dominion over masters, slaves, and Indians, all of whom are to this day, with a unanimity unexampled in the history of the world, warring against your attempts to become their masters. You say that we tried to force Missouri and Kentucky into rebellion in spite of themselves. The truth is my Government, from the beginning of this struggle to this hour, has again and again offered, before the whole world to leave it to the unbiased will of these States and all others to determine for themselves whether they will cast their destiny with your Government or ours? and your Government has resisted this fundamental principle of free institutions with the bayonet, and labors daily by force and fraud to fasten its hateful tyranny upon the unfortunate freemen of these States. You say we falsified the vote of Louisiana. The truth is, Louisiana not only separated herself from your Government by nearly a unanimous vote of her people, but has vindicated the act upon every battle-field from Gettysburg to the Sabine, and has exhibited an heroic devotion to her decision which challenges the admiration and respect of every man capable of feeling sympathy for the oppressed or admiration for heroic valor. You say that we turned loose pirates to plunder your unarmed ships. The truth is, when you robbed us of our part of the navy, we built and bought a few vessels, hoisted the flag of our country, and swept the seas, in defiance of your navy, around the whole circumference of the globe. You say we have expelled Union families by thousands. The truth is not a single family has been expelled from the Confederate States, that I am aware of, but, on the contrary, the moderation of our Government toward traitors has been a fruitful theme of denunciation by its enemies and many well-meaning friends of our cause. You say my Government, by acts of Congress, has "confiscated all debts due Northern men for goods sold and delivered." The truth is our Congress gave due and ample time to your merchants and traders to depart from our shores with their ships, goods, and effects, and only sequestrated the property of our enemies in retaliation for their acts, declaring us traitors and confiscating our property wherever their power extended, either in their country or our own. Such are your accusations, and such are the facts known of all men to be true.

You order into exile the whole population of a city, drive men, women, and children from their homes at the point of the bayonet, under the plea that it is to the interest of your Government, and on the claim that it is an act of "kindness to these families of Atlanta." Butler only banished from New Orleans the registered enemies of his Government, and acknowledged that he did it as a punishment. You issue a sweeping edict covering all the inhabitants of a city and add insult to the injury heaped upon the defenseless by assuming that you have done them a kindness. This you follow by the assertion that you will "make as much sacrifice for the peace and honor of the South as the best born Southerner." And because I characterized what you call a kindness as being real cruelty you presume to sit in judgment between me and my God and you decide that my earnest prayer to the Almighty Father to save our women and children from what you call kindness is a "sacrilegious, hypocritical appeal." You came into our country with your army avowedly for the purpose of subjugating free white men, women, and children, and not only intend to rule over them, but you make negroes your allies and desire to place over us an inferior race, which we have raised from barbarism to its present position, which is the highest ever attained by that race in any country in all time. I must, therefore, decline to accept your statements in reference to your kindness toward the people of Atlanta, and your willingness to sacrifice everything for the peace and honor of the South, and refuse to be governed by your decision in regard to matters between myself, my country, and my God. You say, "let us fight it out like men." To this my reply is, for myself, and, I believe, for all the true men, aye, and women and children, in my country, we will fight you to the death. Better die a thousand deaths than submit to live under you or your Government and your negro allies.

Having answered the points forced upon me by your letter of the 9th [10th] of September, I close this correspondence with you, and notwithstanding your comments upon my appeal to God in the cause of humanity, I again humbly and reverently invoke His Almighty aid in defense of justice and right.

Respectfully, your obedient servant,

J. B. HOOD,

General.

[Inclosure No. 7.]

HDQRS. MILITARY DIVISION OF THE MISSISSIPPI,

In the Field, Atlanta, Ga., September 14, 1864.

General J. B. HOOD, C. S. Army,

Commanding Army of Tennessee:

GENERAL: Yours of September 12 is received and has been carefully perused. I agree with you that this discussion by two soldiers is out of place and profitless, but you must admit that you began the controversy by characterizing an official act of mine in unfair and improper terms. I reiterate my former answer, and to the only new matter contained in your rejoinder I add, we have no negro allies" in this army; not a single negro soldier left Chattanooga with this army or is with it now. There are a few guarding Chattanooga, which General Steedman sent to drive Wheeler out of Dalton. I was not bound by the laws of war to give notice of the shelling of Atlanta, a "fortified town" with magazines, arsenals, foundries, and public stores. You were bound to take notice. See the books. This is the conclusion of our correspondence, which I did not begin, and terminate with satisfaction.

I am, with respect, your obedient servant,

W. T. SHERMAN,

Major-General, Commanding.